We left Boulder around 7 am, heading up over the mountains via the I70. We went through the Eisenhower tunnel then left the main highway, turning onto Highway 24 toward Leadville.

The Eisenhower Tunnel (officially the Eisenhower–Johnson Memorial Tunnel) is a dual-bore, four-lane tunnel that crosses the Continental Divide at 11,158 feet (3,401 meters), under Loveland Pass. At the time of dedication, it was the highest vehicular tunnel in the world. Started in 1968 and completed in 1979, it is the longest mountain tunnel (westbound bore is 1.693 miles, eastbound is 1.697 miles) and highest point on the US Interstate Highway system. The westbound bore is named after Dwight D. Eisenhower (the president for whom the Interstate system is also named) and the eastbound bore is named for Edwin C. Johnson (a senator who lobbied for an Interstate Highway to be built across Colorado).

One of the biggest setbacks was fault lines that were not discovered during the pilot bores. These began to slip during construction. In spite of emergency measures taken to protect the workers, three were killed in the first tube and six in the second. The boring machines also could not work as fast as expected at the high altitudes.

On the way down from the pass were many runaway truck ramps. These steep, gravel-filled paths had clearly been used!

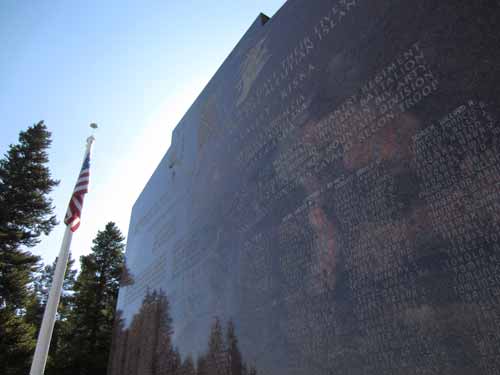

At Tennessee Pass (10,424 ft / 3,177 m) was a memorial to the 10th Mountain Division of World War II.

The memorial, erected in 1959, honors the 992 killed in action and the over 40,000 wounded.

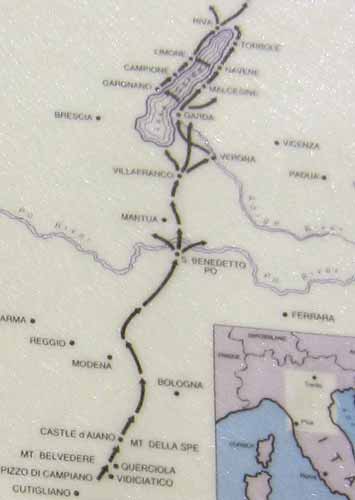

The 10th Mountain Division entered combat against the Germans in January, 1945, in the Apennine Mountains in Northern Italy. Using technical rock climbing equipment and skills, the successfully attacked one of the main German defense positions. They were the only division in the history of the US Army to be organized, trained and committed to combat as ski and mountain troops.

Training trek from Leadville to Aspen. The division was stationed a few miles north of where we were and trained on the nearby ski slopes.

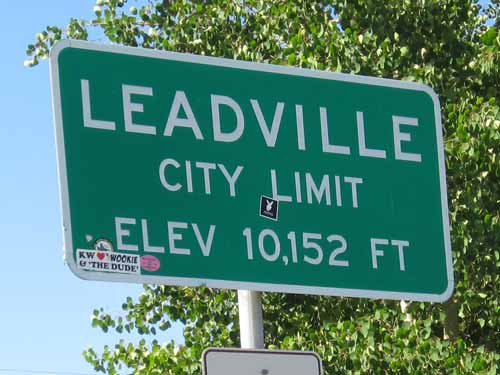

We arrived in Leadville around 10 am. There were so many museums, it was hard to choose what to do. So we asked at the tourist center. They gave us an idea of what to see, as well as a possible place to eat. So we walked a couple blocks down the main street to the Tennessee Pass Cafe. Unfortunately it was quite pricey and the portions were quite small.

Leadville is the highest incorporated city in the US.

At one point, Leadville was the second most populous city in Colorado (Denver was the first). That changed quickly for the mining town with plumetting silver prices from the depression of 1893.

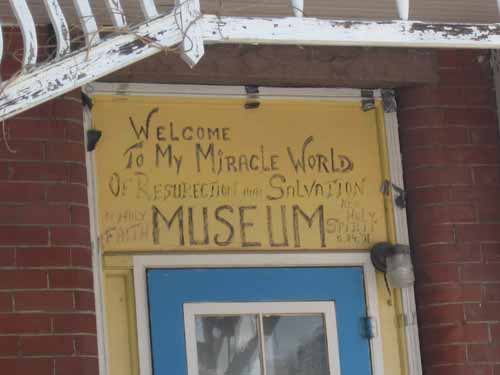

Clearly some colorful characters lived up here. Too much thin air, perhaps?

Cute place...

... not cute food.

The National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum turned out to be a much better suggestion. First were samples of rocks from all around the world as well as various mining equipment and time lines. Then came a wonderful diorama with numerous scenes of gold mining in Colorado. Even more exciting was a "real" underground mine, complete with tracks and various sound effects at the different stations (drilling, dynamite blasting, etc). The remaining rooms were packed full of more interesting things. There was also a giant hall of fame honoring all those related to mining.

Lots and lots of rocks... although we didn't see one from New Zealand.

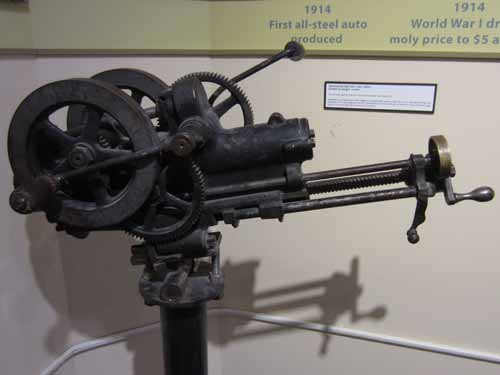

Hand-cranked rock drill, early 1900's

There were no smooth paved roads in the 1800's. Moving large quantities of explosives was often times simply impossible. So powder companies began manufacturing the explosives near the major mining centers.

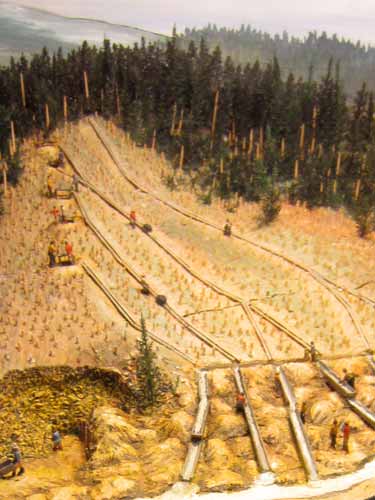

In 1879, prospectors found a bluish-grey mineral on Bartlett Mountain. It was finally identified in 1895 as molybdenum (pronounced muh-LIB-den-um), which had great potential as a steel alloy. Today it is used almost everywhere... in cars, buildings, our homes, etc. Block cave mining was used for excavation of hard materials, such as molybdenum, found deep underground. It leaves no waste piles on the surface and no large open pits. This is a model of the Climax molybdenum mine which began 1972.

Something you don't see every day... a coal car in stained glass

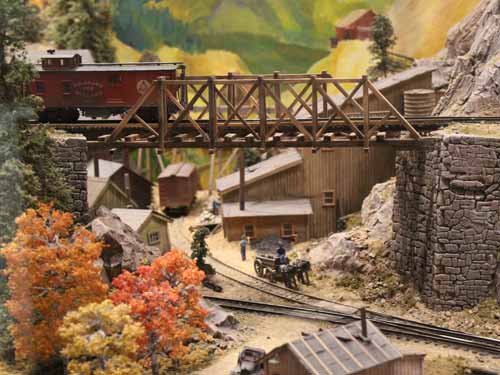

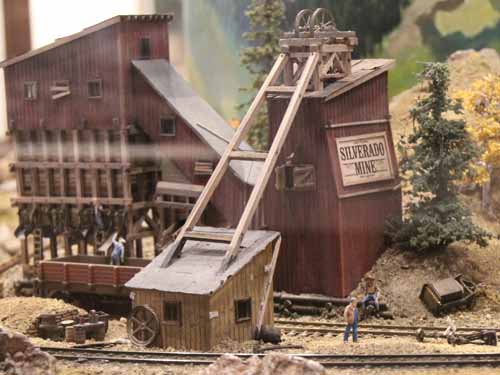

Regan investigates a model train display...

The detail was simply marvelous!

The train passed through all kinds of local scenes from the past.

Note the guy fixing the roof... and the stage coach

Takin' a short break behind the shed!

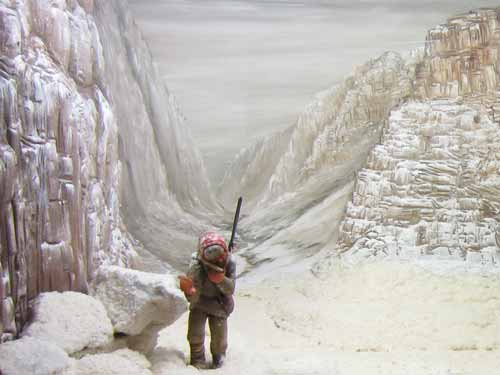

After a car accident in 1949, Hank Gentsch was told he was totally disabled. But he was determined to rebuild his life. He turned to woodcarving and began making tourist items. Eventually he created "An Adventure in History" - a giant exhibit about the development of Central City and its first gold discovery in 1858. This history is similar to many others throughout many of the western states.

In December, 1858, George Andrew Jackson, a prospector from Missouri, travelled to Colorado on a hunting trip. After bagging an elk, his companions returned, but he continued on alone. This solo mission would lead to one of the first discoveries of gold in the Rocky Mountains.

John H. Gregory's strike would prove to be one of the richest lodes in Colorado.

Harry Gunnell finds gold at Eureka Gulch.

Miners began to devise fast and efficient methods to separate gold from dirt and gravel. Most of these required wood boards. Laying a tree across a gully, two men using a whipsaw could quickly cut the long planks. Slowly, with the arrival of more and more prospectors, trees began to come in short supply.

Water was also needed in large quantities. A rocker was designed to be first filled with gold-bearing gravel. Water was then added while the miner rocked the box back and forth, causing the fine gravels to float off and the gold and other heavy metals to get caught in riffle bars. It worked best with a team of four.

The "long tom" worked on the same basic principle as the rocker but could handle much more material. Water was funneled into the long tom from a creek while gravel was dumped into the upper end.

The sluice box was an improved version of the long tom. It consisted of a series of riffle boxes which would catch the heavier gold.

As the free gold in placer deposits became more difficult to find, miners began searching for the source of the placers. This led them to gold encased in solid quartz. To break if free, miners used arrastras, which were basically large pits filled with heavy stones that were dragged around by a horse or ox (later by steam power). This pulverized the rock which could then be sifted through.

As more claims were developed further from creeks, giant wooden flumes were built to bring water in from up to 11 miles away.

Prospecting was hard work. Even in the early days, when placer mining was good, miners barely scraped by. Many returned home broke; others died from the poor conditions; and still others went to work for the larger mining companies in the underground mines. Here, conditions were often even worse. A worker was expected to load 18 one-ton cars per 10-hour shift... for $2 per day.