Working the elevator which lowered the men into the mine

As a miner began his shift, he removed his brass from the brass board and took it with him into the mine. He returned it once he was back on top. This way, all miners could be accounted for at the end of each shift... or worse, identify who had to be rescued if there was a cave-in.

Reaching the bottom of the mine

The proverbial canary in a coal mine. Since birds are more sensitive to poisonous gasses and poor air quality, they would indicate (by dying) when the miners needed to get out quickly.

Cart tracks ran though the length of the exhibit.

The sounds of rock drills and other 'mine noises' accompanied the various sections of the exhibit.

Not all the explosives will detonate at once. They will blast in concentric rings, creating a larger and larger hole. Finally, the bottoms ones will detonate, moving the broken rock away from the face.

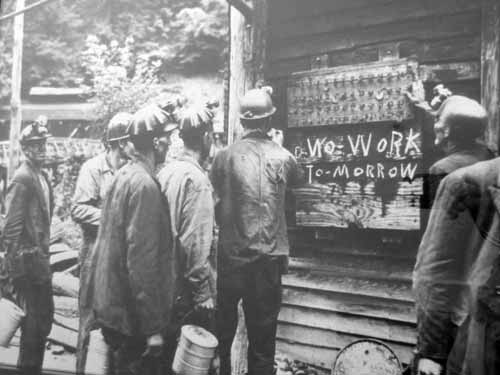

Not sure what this means, but it was probably important!

Heading back up after a long, hard day

The Mining Hall of Fame:

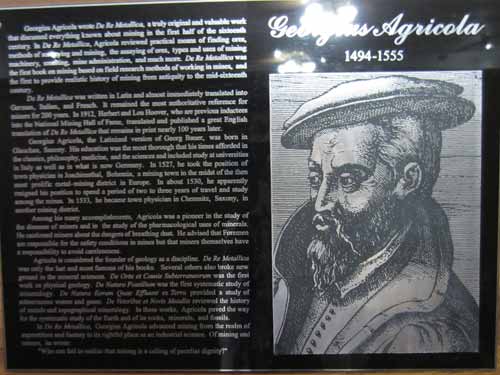

Georgius Agricola wrote "De Re Metalilica," which was everything known about mining in the first half of the 16th century. It remained the most authoritative reference for miners for 200 years.

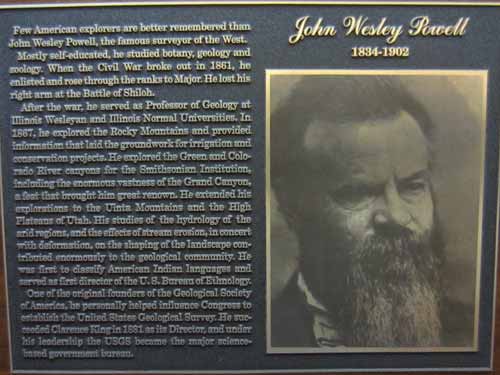

Along with being the first to navigate the Grand Canyon by raft, John Wesley Powell was one of the original founders of the Geological Society of America.

J. David Lowell proves you don't have to be dead to get into the hall of fame.

There were still several large areas to explore, all filled with historic mining artifacts and photos.

A room of beautiful things that came out of the earth

Worth its weight in gold

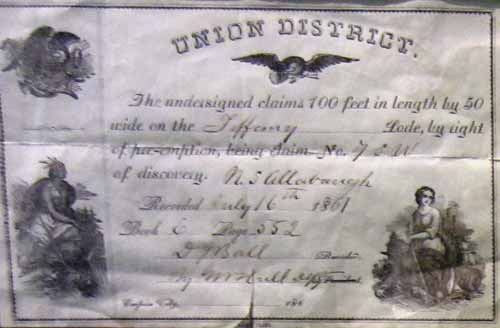

An early mining claim from the mid-1800's

Getting ready to set off a fuse, 1910

Working the rock drill

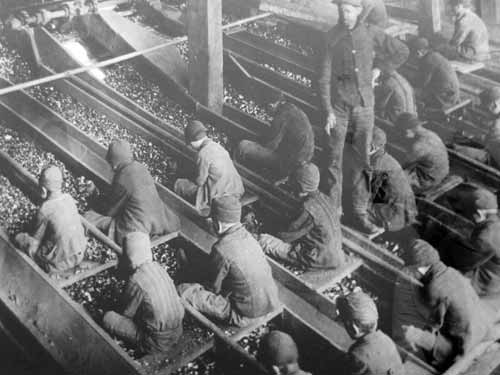

These look like they could be kids working the sluice boxes!

Grabbing tags from the brass board. Note the round lunch pails.

We headed back to the car via some back alleys, then hit the road again toward Buena Vista (you might be tempted to pronounce it 'Bwayna Vista' but you'd be wrong; apparently it's "Boona Vista"). There we turned onto a road that used to be the old stagecoach route up to St. Elmo during the mining boom in the late 1870's. It was paved most of the way, but the last 5 miles were gravel (still a good road though).

A hidden bell tower

The side of the church

Interesting.

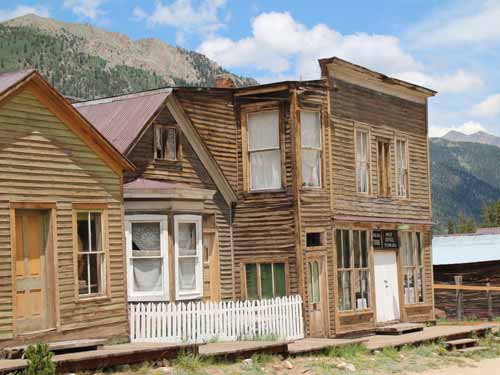

Heading toward the 'hills'

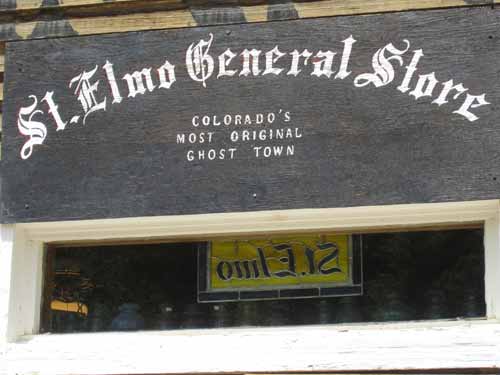

When we got there, the area was jam-packed with people... in cars, campers, motorcycles, atv's, etc. Now, if you read about St. Elmo on the internet, it will spin some yarn about it being a 'ghost town'. It isn't. Nothing's really abandoned (all of the buildings are owned and some are even restored) and there are still residents in very nice houses just off the main street. All in all, it felt rather fake and touristy. But, we still tried to take some nice photo's anyway... although sometimes it involved some waiting for the large groups of people to pass.

The town was originally named Forest City. However, there already was a Forest City in California, so the post office wouldn't allow it. They then chose St. Elmo, possibly after a popular novel of the time by Augusta Evans.

The town's story: Abundant water and game had always drawn Native Americans here. In the 1860's the area was also used by ranchers for grazing cattle in the summer. The trappers and prospectors arrived in the early 1870's. In 1875, silver ore was discovered nearby. Add to that the arrival of the railroad in the 1880, and you have people pouring into the area. It reached an estimated peak of 2,000 in 1881. There were at least 50 mines in the area, producing gold, sliver, zinc and lead. The largest mined 75 to 100 tons of ore per day in 1881. Two fires, combined with the silver crash in 1893, began the city's slow decline. The railroad closed down in 1926 and the tracks were pulled up. The largest mine closed in the 1930's.

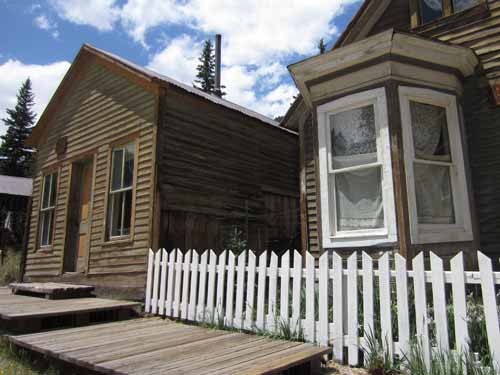

The ghost town feel:

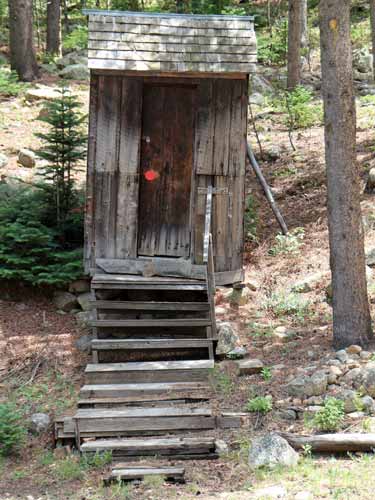

A lopsided outhouse

Abandoned, rusty items in the yards

Creative kludging

Chipping and faded paint

Square nails. Nails give clues to the history of a building, especially those constructed during the 19th century, when nail-making technology advanced rapidly. In the old days, nails were made one-by-one by a blacksmith. Between the 1790's and the early 1800's, various machines were invented for making nails from bars of iron. The earliest ones are known as type A cut nails. By the 1810's, a more effective design was developed, and these nails became the type B nails (as seen above). Starting in the 1880's, soft steel wire could be used (the round nails we know today), and by 1913, they had all but replaced the old iron nails.

The NOT so ghost town feel:

If you have a sign announcing it, you probably aren't it.

Not to mention a working store packed with sodas and souvenirs

The Stellar's Jay is a common opportunist found where people are.

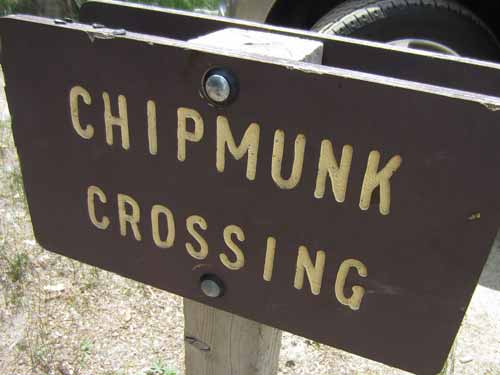

Cute... but this is supposed to be a ghost town not a tourist resort, remember?

Brand new walkways for the tourists

Fresh paint

More fancy upkeep. The false building fronts, so common in the old Wild West towns, were almost always used for commercial purposes. It was a way to make hastily built towns look more like the established commercial buildings back East. In Colorado, the false fronts not only made the buildings look more impressive, they also helped hide the view of the surrounding mountains that reminded residents they were not back home.

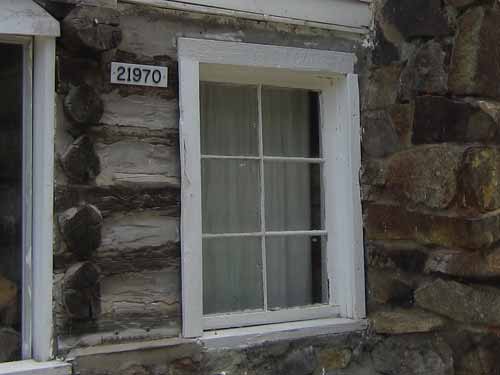

A building address

Flowers in the windows

A satellite dish

Wires