Minuteman Missile National Historic Site

Even though we arrived before the station opened, there was already a line and we didn't get on the first tour. But we got on the second one at 9 am. Having some time to kill, we first looked around the station.

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite into space which brought the Cold War (which many Americans saw as the resistance to Communism) even closer to home. If the Soviets could launch a satellite into orbit, then they could easily send a nuclear warhead all the way to the US.

In 1961, with the fear of a Russian attack, the US planted 150 Minuteman II missile sites across South Dakota within a period of just 2 years. Each missile could deliver a payload equal to 60% of all the bombs used during World War II. The sparsely populated Great Plains provided an ideal place. The missiles were far from the oceans and Soviet submarines. Other sites were placed in the surrounding states.

Many of the silos were installed into the lands of old homesteads.

And so, the arms race was on. It wasn't until the 1980's that talks of peace began, but it took until 1991 before an actual arms reduction began. This lead to half of the Minuteman missiles being decommissioned and the eventual establishment of this national historic site. Today, however, there are still 500 active Minuteman III missiles on duty.

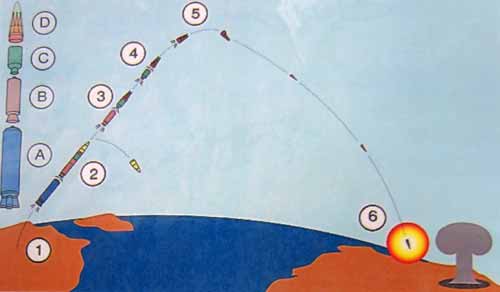

The Atlas D, the Titan I, and the Minuteman II. The Minuteman could travel over 15,000 miles per hour, was 56 feet tall, 5.5 feet across and weighed 65,000 pounds.

Deploying the 1.2 megaton nuclear warhead

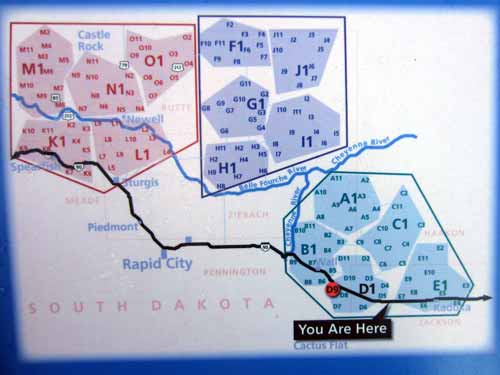

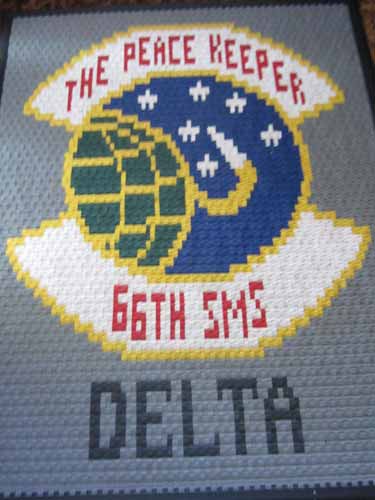

This area was part of the 66th Missile Squadron. Each squadron had five LCCs (or Launch Control Centers). For the 66th squadron, those centers were labelled as Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta and Echo flights, each in charge of 10 missiles. Every missile and LCC had to be at least 3 miles apart, with the missiles not being more than 15 miles from their LCC.

We would also get to visit the missile silo D-9 (Delta 9), which is the red dot. The "You are here" is the ranger station, and the LCC for the Delta filght would be located in the center of the blue D1 shaded area.

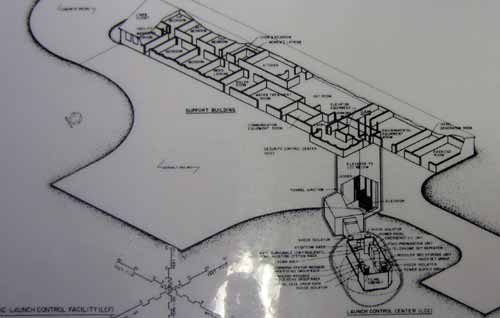

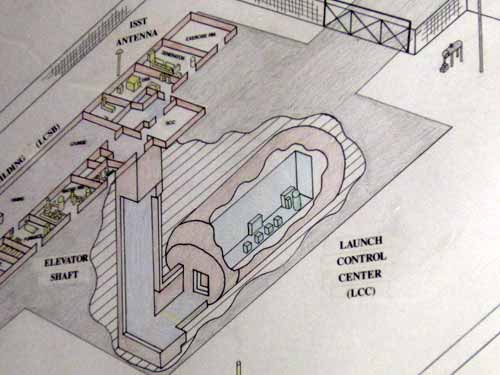

The LCC was buried deep beneath the Launch Control Facility. It was completely secure and had its own power and limited supply of oxygen should anything happen to the building above it.

It was a small area, meant only for 2 people, which is why the tour groups were kept so small.

We still had a bit more time before our tour, so we headed back down the road to an old sod house homestead in the early 1900's. Unfortunately the entry fee felt a bit too pricey, so we consoled ourselves with a nearby giant prairie dog.

We were still a bit early but we headed out to the command center (the LCC) anyway. From the road it was practically invisible, and it was highly believable that people could have driven by these things for decades without ever thinking twice about them... and CERTAINLY not thinking it was a nuclear missile control center!

The center as seen from the highway

We turned off the highway and reached a dirt road which lead us to the Delta-01 LCC. The building was designed to look like an average ranch house (if you ignored all the high protective fencing).

Apparently this site (and the silo) were selected to be preserved because 1) they were the most typical and least altered from the original 1961 design and 2) they were easy to get to (right off the highway).

"Freedom is not free"

The facility had its own gas pump (not free, but at least convenient).

We were let into the complex and first given a tour of the Launch Control Facility above ground.

A piece of the rebar used to construct the underground portion of the building

The highly reinforced communication cable. It was imperative to keep in contact with the launch control centers no matter what.

Some of the beautiful decor of the 1960's

The dining room...

... and entertainment room. I love the woodland wallpaper!

Peace through giant weapons was (and still is) a strong belief.

Entering the security command center

This intercom was state of the art in its time.

The ranger told us that on a previous tour, a little boy was very excited to see that phones used to be "attached" to a spot (especially with a cord).

While all of this may seem such a long time ago, it really spanned a long time.... from the late 1940's to the mid-1990's. Not only did my parents have the Cold War in their lives for a long time, I did too. I remember such slogans as "Better dead than red" and having to do drills practicing hiding under our desks for when the Russians attacked. It was very scary, mostly because it was so vague.

The LCC was 30 feet underground so we had to take an elevator.

Ooooh... scary. The people in charge of our national safety couldn't even spell?

The ranger manually closes the elevator door.

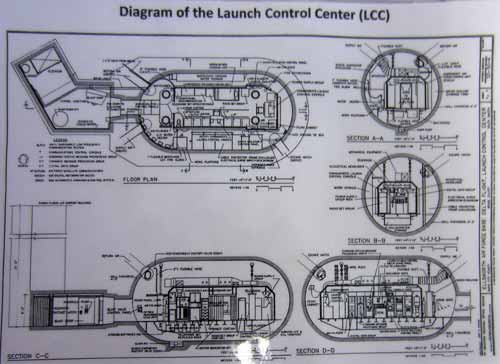

We exited the elevator and approached a giant vaulted door. Behind that was a narrow, very low passageway that led to the LCC (Launch Control Center). There were many features designed to isolate it from any kind of outside force - including that it was completely suspended.

We then entered the LCC. The missileers worked in 24-hour shifts. Their primary duty was to be ready to launch the missiles if they received the orders. From that point, it would take less than 5 minutes to complete the launch sequence. Two crews within the same squadron had to turn their keys at the same time. Once completed correctly, the missiles would blast from their silos within 30 seconds.

To launch, all four keys (two here and two in another squadron) had to be turned simultaneously. The inserts were placed 12 feet apart so that one person couldn't turn both keys at the same time.

In the event only one of the missileers turned their keys, there would be 1 1/2 hour delay before the missiles launched and alarms would sound in the other LCCs within that squadron. If it did turn out to be an unauthorized launch, any of them would be able to inhibit it with the turn of a knob (on the far right in the above picture).

The ranger then told us stories of some close calls, on both sides. In the US, the main computer once malfunctioned and started sending launch codes. Fortunately these didn't match the ones the missileers had and the problem was quickly detected. The Russians once mistook the silver lining on a cloud as an incoming missile and gave the order to launch. Knowing that he was potentially starting World War III (and destroying most of the planet), the commander questioned the order instead of just pushing the button. By then, the others had realized their mistake and cancelled the order. His reward? He was demoted for not following orders!

We then returned back to the elevator and headed upstairs.