CABRILLO & LA JOLLA (Day 8 - part 1)

After a delicious hotel breakfast involving a cheese omelet and french toast, we drove out to Cabrillo National Monument, located at the tip of a peninsula.

Click for a larger view

Click for a larger view

In 1906, the president became authorized to set aside significant historic and scientific sites. So in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed a portion of Point Loma as Cabrillo National Monument, honoring Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo (we had briefly learned about him at the mission) who was the first European explorer to land on Alta California in 1542.

In 1932, the site was designated as California Historical Landmark #56, and the following year, President Roosevelt transferred authority to the National Park Service. At the time, it was the smallest unit in the park system, encompassing only 1/2 acre. Major renovations were done, including refurbishing the deteriorating lighthouse and building a new road.

The area was off-limits to the public during WWII because the entire south end of the Point Loma Peninsula was reserved for military purposes. After the war, however, the area was significantly enlarged by Presidents Eisenhower and Ford. In 1965, the visitor center was built and improvements to trails, parking areas and other features were made. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966 and currently includes some 160 acres.

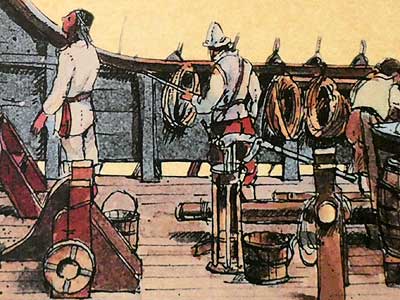

Conquistadors

There were no official military uniforms in the 16th century so soldiers just wore what they had. Some had metal helmets and restrictive breastplates, others preferred leather and canvas vests with metal plates sewn in. Metal neck, knee and thigh protectors added more weight and were also hot to wear. Most of them quickly adopted the thick, quilted cotton armor worn by the native inhabitants.

Golden treasure

"They died in the service of God and of his Majesty and to give light to those who sat in darkness - and also to acquire the wealth which most men covet." - Bernal Diaz del Castillo

From the mission, we learned that Christopher Columbus' discovery of a "new world" in 1492 unleashed a half century of exploration. The Spanish monarchs received one-fifth of all the treasures found in the Americas, therefore they hoped their conquistadors would uncover incredible riches to finance their dreams of becoming a leading European power.

The Spanish believed they had an obligation to conquer this new world. Not only was it was their duty to the Catholic Church to bring Christianity to the "heathen" natives, they also felt it was their right to the land's riches.... including the mythical cities of gold.

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo (circa 1497 - 1543) had arrived in the New World by 1520 and became a corporal of crossbowmen under Hernan Cortes in Mexico.

Mayan warriors (left) throw rocks to defend their home during the conquest of Mexico.

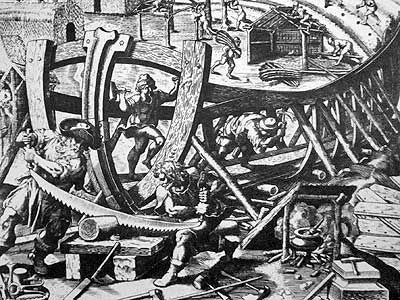

There was also the hope of finding a western route to the Orient. Cabrillo was commissioned to build a fleet of 13 ships, so he established a shipyard in Guatemala.

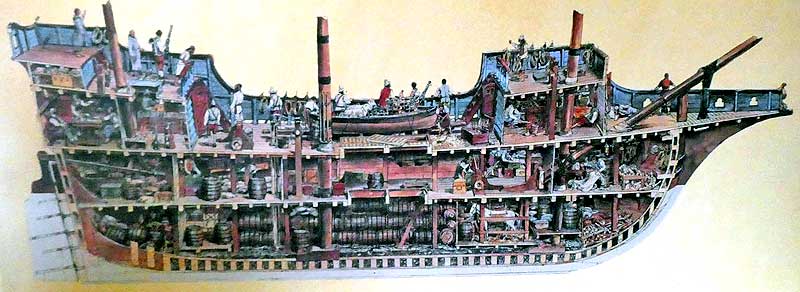

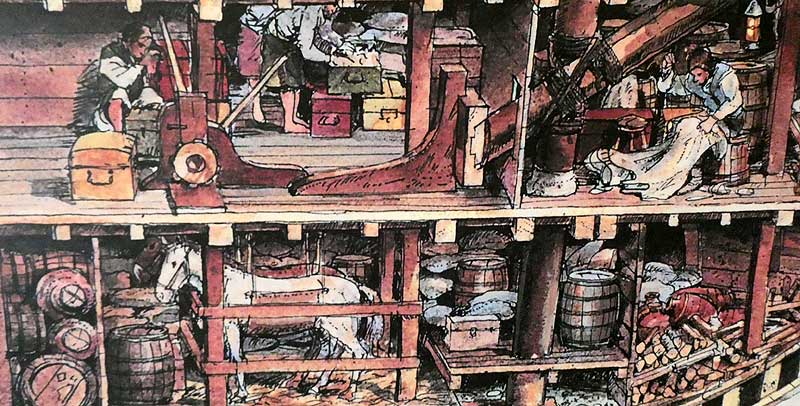

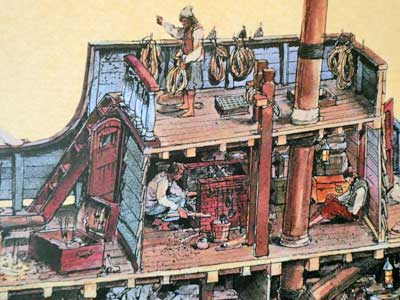

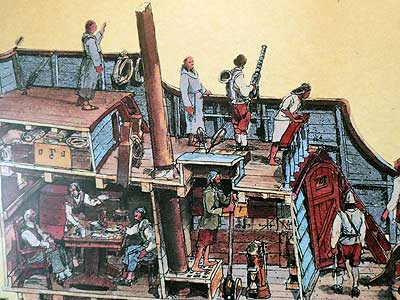

The cross-section of a galleon, a type of ship frequently used by the Spanish in the 1500's. Designed for warfare, these ships were narrower and more maneuverable.

Cabrillo built his flagship, the San Salvador, sometime between 1536 and 1540. It was 80 feet long and 22 feet across the beam. It carried about 100 people... 4 officers, 30 seamen, 3 apprentices, 25 soldiers, a priest (as well as a couple of brothers), servants, slaves and even a few merchants with their goods.

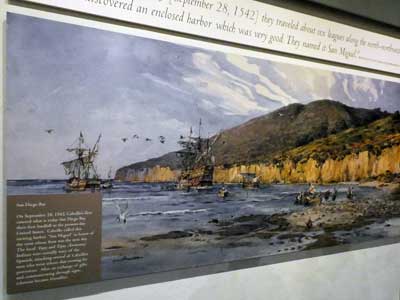

In 1542, his fleet entered San Diego Bay, their first landfall in the United States. He called the harbor San Miguel in honor of the saint whose feast was the next day. The local people were initially wary of the Spanish and attacked several of the men who went ashore that evening for provisions. After an exchange of gifts, however, they became friendlier.

(right) Prince Henry the Navigator (1394 - 1460)

Cabrillo used the most sophisticated navigational tools of the time. Sailors were able to calculate latitude using the sun or North Star, but since no accurate timepiece existed then, they could not calculate longitude. They were forced to rely on "dead reckoning" by using the ship's speed and unreliable charts.

Early navigators used an astrolabe by turning the pointer until a star or planet could be seen in a straight line through both pinhole sights. They then calculated latitude by noting the angle of the object above the horizon.

A nocturnal was used to determine what time it was at night. After sighting known constellations such as the Big or Little Dipper, navigators could determine the time by noting where the pointer stood on the date and hour of the disks. ... The quadrant was also used to determine latitude.

The compass is one of the oldest and still most widely used instruments. In the 1500s, dry-card compasses were often a card with magnetized bars of iron on its underside. They were not submerged in water or oil, hence their name. ... The sand glass was used to help calculate distance. By measuring the speed of the ship with a plumb line, sailors would then measure each half hour of time with this glass and thereby be able to roughly estimate distance. Accurate sea-going clocks were not invented until the 1700s.

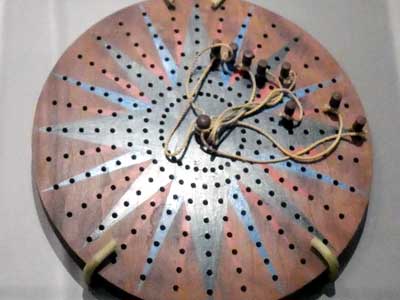

Since ships rarely traveled in a straight line, navigators needed to know how often and how long they veered off line. A traverse board was used to calculate the number, direction and distance of each zigzag. ... A sounding line and weight were used to measure the water's depth to ensure the ship wouldn't run aground.

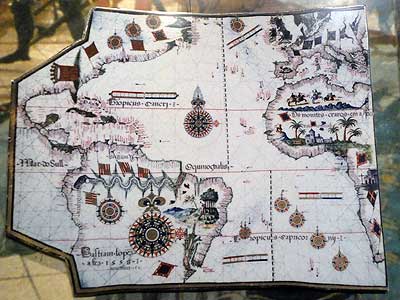

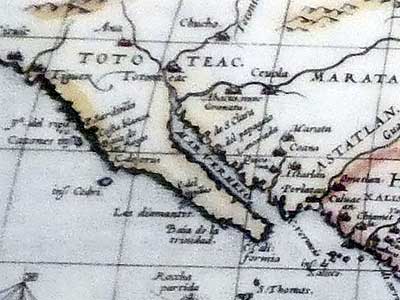

Mapmaking in the 1500s relied on equal parts fact, guesswork and fantasy. Cartographers created accurate charts of land which had already been explored. Cabrillo carried with him a fairly detailed map of lower California pieced together from earlier explorations.

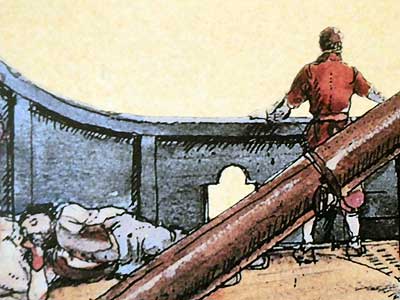

The details of Cabrillo's death are as mysterious as those of his birth. One account says that he fell in 1542 and broke leg. Another says it was an arm near the shoulder. Presumably, complications ensued and he died in 1543. But was he buried at sea or on one of the local islands?

The first conquistadors were lucky if they returned home alive. Cabrillo, Hernando de Soto (c. 1497 - 1542) and Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478 - 1541) all died during their expeditions, while Panfilo de Narváez (1470 or 1478 - 1528) simply disappeared without a trace. Francisco Vazquez de Coronado (1510 - 1554) survived but was put on trial for alleged mistreatment of the natives (he was acquitted of all charges). Only Hernan Cortes (1485 - 1547) lived a full life.

Cabrillo's expedition was considered a failure since he found no gold, treasure, exotic spices of trade route to Asia. They did return with the first recorded account of the people, places and climate of California at least. In the centuries the followed, the galleons sailed past this area, rarely venturing near land. Sebastian de Vizcaino retraced Cabrillo's route in 1602, creating new charts and changing many of his place names. It wasn't until 1769 that spain established a colony in Alta California.

return • continue