CABRILLO & LA JOLLA (Day 8 - part 2)

Outside, there was a lovely area overlooking the bay.

Red and green buoys (or lights) indicate primary channels.

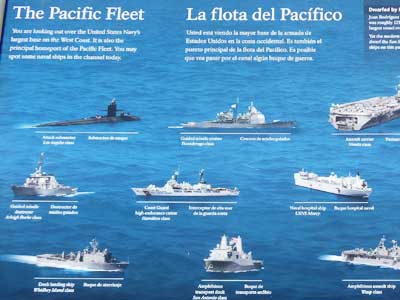

Heading out to open water ... returning to the harbor

"Right Red Returning" - In most circumstances, this phrase works as a reminder of the correct course when returning from open waters or heading upstream.

Wow! A submarine! And according to the buoy, it's heading out.

A statue in the distance

We made our way over to the monument. In 1939, the Portuguese government commissioned a statue of Cabrillo and donated it to the U.S. The sandstone statue was 14 feet tall and weighed 14,000 pounds. It was intended for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco but arrived too late. After being stored in a garage in Oakland for a while, it was shipped to San Diego where it was stored for several more years. It was was finally installed here in 1949. Due to severe weathering because of its exposed position, it was replaced by a limestone replica in 1988.

Cabrillo was listed by some historians as Portuguese while others claimed him to be Spanish. In 1615, historian Antonio de Herrera listed him as Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo Portuguese, with this extra last name implying his origin. However in 2015, a researcher discovered he was actually a native of Spain.

A view uphill at the lighthouse

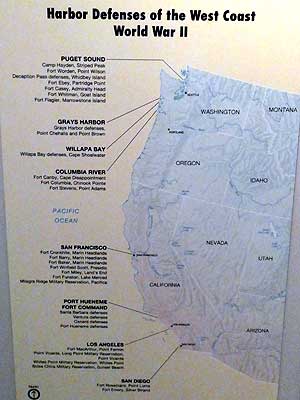

We then followed a path to a small building which once served as a radio station used to help defend the San Diego Harbor during WWII. San Diego was considered a prime military target. In 1941, ship repair yards, supply depots and other support facilities lined the shores of the bay. The area served as a principal staging port for troop, supply and naval convoys in the Pacific.

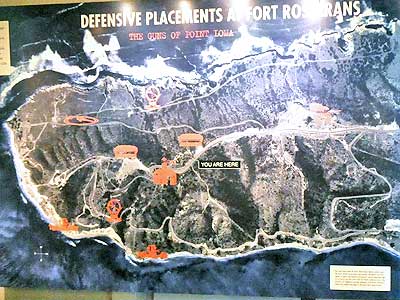

The history of Fort Rosecrans:

The original fortification at Point Loma (known as Castillo Guijarros) was built by the Spaniards sometime between 1797 and 1798. By 1840, the low earthen-walled fort had fallen into disuse.

In 1852, President Millard Fillmore set aside this area for military purposes (as the Fort at Ballast Point). Initially, however, the executive order had no funding, but by 1873, the whalers had been evicted and construction had begun. In 1899, the fort was completed and renamed Fort Rosecrans after Major General William S. Rosecrans, a Civil War general and California congressman.

Over the next 17 years, the number of people stationed here varied widely. For the most part, the fort served as temporary housing for troops that were needed elsewhere. During World War I, it was fully staffed with four 10-inch guns, two 5-inch guns, two 3-inch guns, and eight 12-inch mortars. It also served as a training ground.

After the war, it had minimal staffing levels and almost no activity. Because of the good weather, it became a highly desirable duty station, but only highly experienced servicemen had enough seniority to be posted here.

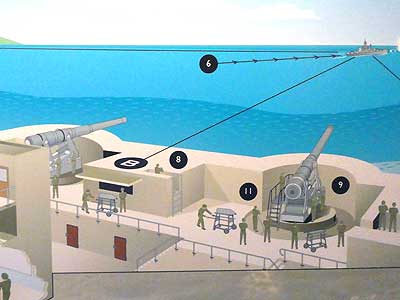

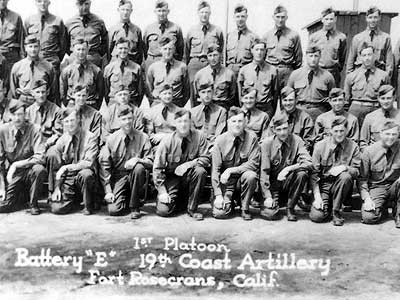

As the real threat of war in the Pacific loomed in connection with WWII, several new 8-inch guns and 155mm howitzers were installed, and by 1943 two 16-inch battleship guns had been added. From 1940 through 1944, it was garrisoned by the 19th Coast Artillery Regiment.

Immediately following the war, Fort Rosecrans was no longer considered strategically important and officially abandoned. The land surrounding the old Point Loma Lighthouse was turned over to the National Park Service, and by 1959 the rest of the facilities were transferred to the Navy.

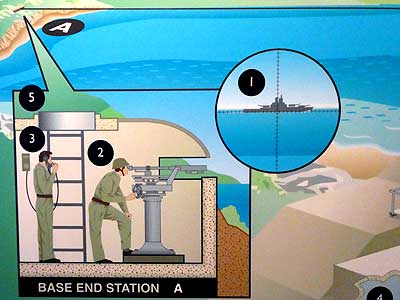

The buildings were part of a larger coastal defense system.

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, most Americans assumed the war would be fought elsewhere. In 1942, a Japanese submarine crept close to shore and fired at an oil installation near Santa Barbara. While little damage was caused, panic set in. Troops shot 1,440 rounds at non-existent airplanes and newspapers reported civilian sightings of Japanese tanks in Malibu Canyon.

Three-man teams operated 24/7, communicating with ships entering the channel. It was also used as a meteorological station to support the coastal artillery. It recorded wind, air density and other conditions that could affect gunfire.

Soldiers spent thousands of hours in concrete stations looking through binoculars for anything unusual that could represent danger. It was the duty of the observer to spot the enemy first, then track and report its movements to those soldiers at the gun positions. During the war, 61 possible enemy targets were spotted... although most turned out to be fishing boats or whales. Others were never identified.

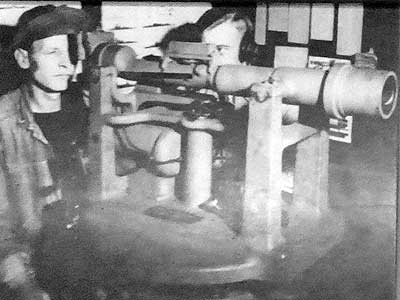

Azimuth scopes were used to measure horizontal angles towards targets. The minimum crew was two men, one to keep the scope on target, the other to read the bearing angle.

Hitting a moving target at 25 miles required precision. The target's course and speed had to be determined; gunners measured temperature and humidity to estimate the muzzle velocity of the projectile; even the arc of the projectile's trajectory along with the effects of the earth's rotation had to be calculated before the gun could be aimed and fired. These observations were done exactly every 20 seconds and it took three sightings (one minute) to accurately locate a target. Everything was mathematically calculated and then telephoned to the gun position.

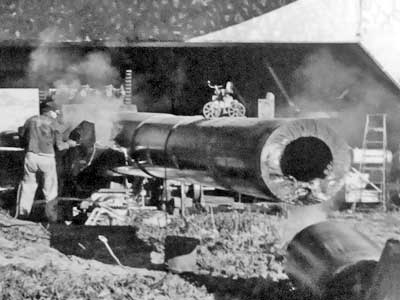

(right) This is a full scale model of cross section of 16-inch gun barrel (the largest gun in the U.S. arsenal). Four years later, these guns were declared surplus. Long range bombers and the atomic bomb made them obsolete. By 1952, the guns were dismantled and sold for scrap.

Battery E ... A gun being melted down.

return • continue