THREE ISLANDS CROSSING (Day 4 - part 1)

We grabbed a hearty breakfast at AJ's Restaurant, then drove east.

Our first overlook was at Two Island Crossing, at Glenns Ferry. After having just traveled for two days across a desert with no water available, many emigrants and pioneers following the Oregon Trail decided to cross the Snake River here, at the mouth of Rosevear Gulch. Most continued downstream two miles to Three Mile Crossing. The Snake River was their largest river obstacle. They sometimes lost their wagons, stock and even their lives.

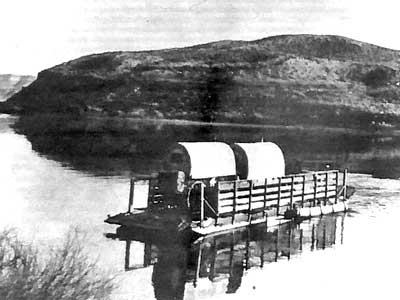

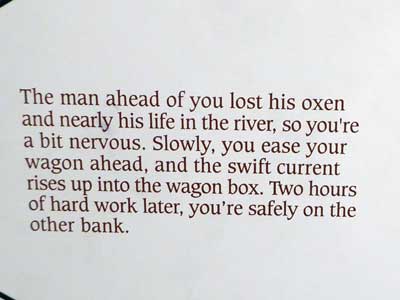

The water here was too deep to ford, so wagons had to be floated across. Holes were plugged with clothing; wagons were caulked with whatever materials were available; wheels were removed and loaded into the wagon. Usually one person would swim across with a rope, so the wagon boats could be pulled over. Others tried to row them across. Cattle were forced to swim.

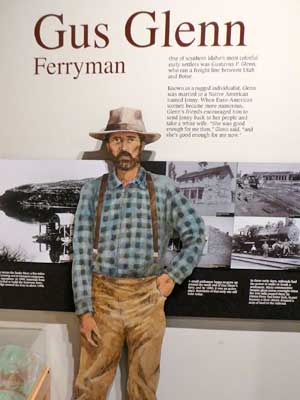

After the cross-country railroad was completed in 1869, Gustavus Glenn, who was a local rancher, set up a ferry to service heavy freight wagons, farms and ranches. In 1890, Rosevear's Ferry (by Joseph Rosevear) replaced Glenn's Ferry until 1908, at which time a bridge was built.

Pulling by rope ... Rosevear's Ferry

We continued on to Three Island Crossing State Park.

A day park's pass only cost a little bit more but would allow us into other nearby parks for free!

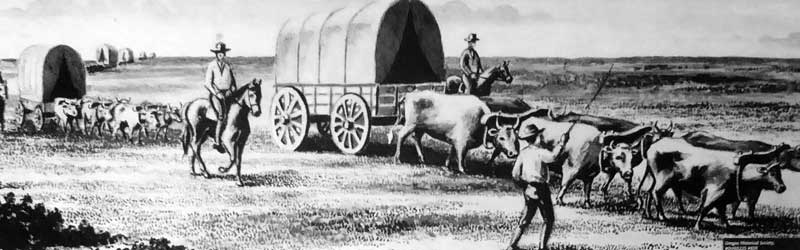

Contrary to popular belief, not all wagons were like this large, heavy Conestoga wagon, which was commonly used back East. Lighter, smaller, sturdy wagons (called prairie schooners because their white covers looked like sails) were better for oxen to manage. There were no seats in the wagon since every last inch was used for supplies. The people had to walk the entire way (shoes wore out quickly along the 2,000 miles of trail).

The Oregon Trail History & Education Center

Click map for a view of the entire Oregon Trail

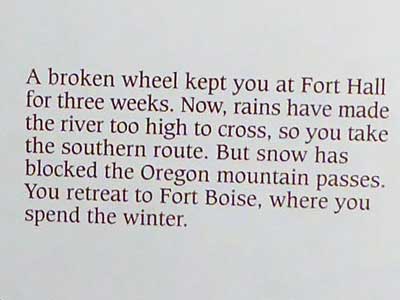

At this location, pioneers rode their horses and drove their wagons across the river. Those who couldn't, faced a much longer, more difficult southern route. There were substantial risks with either decision. Cross here at great risk but have plenty of water and grass the rest of the way, or deal with lack of water and food on the other trail, possibly even missing Fort Boise to restock.

About half of the 53,000 Oregon-bound emigrants crossed here. Most crossings were attempted in late July or early August, when the river was 2 to 4 feet deep. This could still take hours. Things that couldn't get wet were placed as high in the wagons as possible. If water ran into the wagons more than a few inches, there was a chance of it being overturned.

Three Island Crossing. Currents could be very swift between the islands.

Native American tribes, including the Shoshone, lived in this area. They survived on seasonal salmon runs and gathering. In the winter, they moved south. Horses had been brought to the New World by the Spanish conquistadors in the 1500s, and by the early 1700s, horses were an invaluable part of the local cultures of the Snake River Plain.

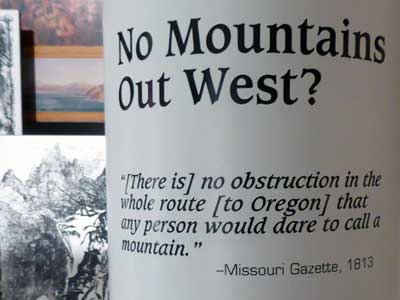

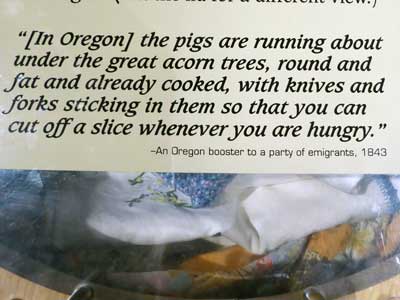

In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the country, sparking an even greater expansion westward. Manifest Destiny was the belief that the pioneers had the right... obligation, even... to settle this land from coast to coast. By the early 1840s, this manifesto was combined with practical reasons to motivate many to make the hard journey. Epidemics such as typhoid, tuberculosis and cholera were killing large numbers of people. It was rumored the air was purer out west. In 1837, the country had suffered it first financial collapse. People were unable to by their mortgages, and farmers looked for free land and fresh starts.

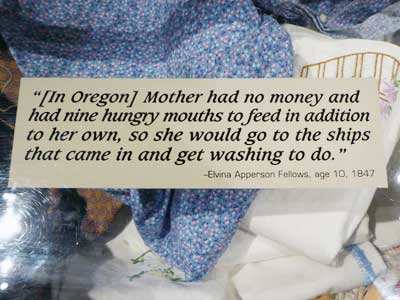

Those who had never set foot in the West claimed it was a paradise. Others argued the journey would be absolutely impossible for entire families with their possessions. Most emigrants found the journey to be difficult and perilous, but doable. However, the paradise at the end of the road still meant plenty of hard work and times.

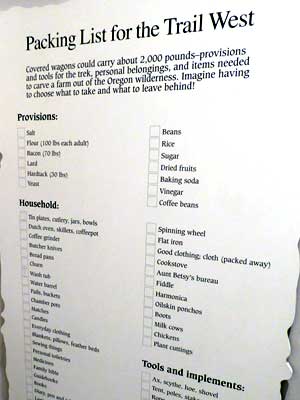

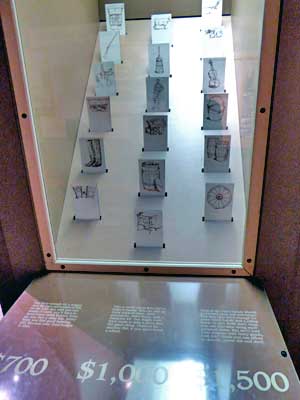

What to take? Items cost money and took up space. For $700, you would have a wagon and the bare necessities. It would be a risky trip, with possibly not enough food or oxen. For $1,000 (worth about $20k today), you got an extra team of oxen, more provisions, extra boots and even a medicine kit. You might even have enough room to take a plow or good dishes. If you didn't break a wheel, your chances of success awerere fair. For $1,500, you could have enough for a couple of horses and hired hands. But don't overload your wagon. That could be fatal.

Most wagons were pulled by oxen (neutered bulls). They cost less than mules, hauled heavier loads, ate anything, and didn't run away. They were slow, however.

Look at this kid's face! So believable!

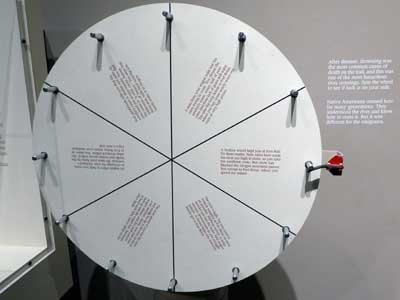

Spin the wheel and see your fate. This was mine.

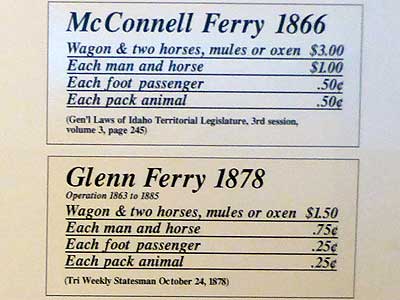

There were many ferry sites along the river beginning in the 1860s. But these cost anywhere from 40 cents to $16.

We already learned of Gus back at Two Island Crossing.

Trade and setting up camp

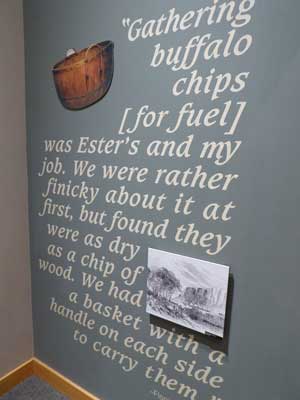

4 am - get up, hitch the teams, make breakfast over a buffalo-chip fire

7 am - roll out!

Midday - rest and eat leftovers

5 pm - circle the wagons to form a corral for livestock (not for protection against attacks)

Dinner - dig trenches before lighting the fire (to prevent sparks from causing fires); cook a meal of beans, bread, bacon; wash dishes

Evening - visiting, dancing, singing, exploring, sewing, laundry

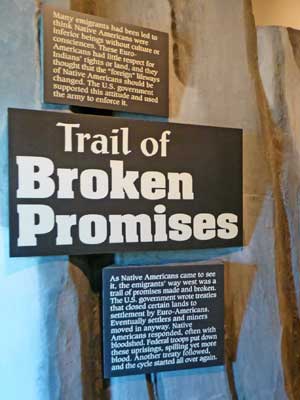

At first, relations between the emigrants and the tribes of the Snake River were friendly. There was trade and an exchange of knowledge. Over time, however, many settlements became important points along the trail and began to grow. The two cultures began to compete over the same space. Native Americans began to resist the settlers' threats to their way of life.

By the late 1870s, Euro-American settlers and miners had claimed most of the Snake River Valley. Many emigrants had been led to think of the native peoples as an inferior culture. The U.S. government supported this attitude and used the army to enforce it. Most of them were moved to reservations. But the poor conditions there led to a skirmish in 1878. Since food was scarce, a party of Bannocks was allowed to leave in search of roots. Discovering that settlers' pigs has dug them all up, they formed a war party with the Paiutes and attacked the communities. The war ended after several months, and the Paiutes were moved to a reservation in central Washington. Over 500 men, women and children were forced to march there.

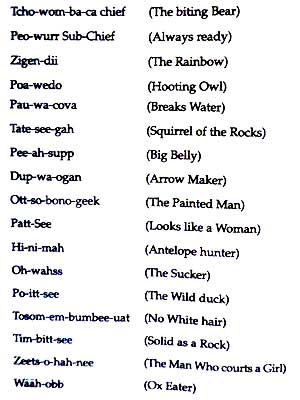

Some of these native names definitely have a story behind them!

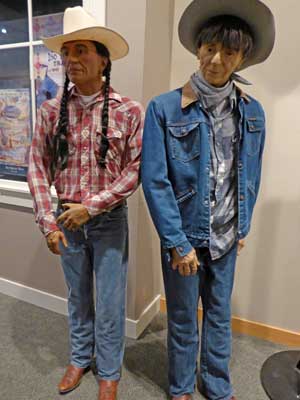

I couldn't find a sign explaining these guys...

... but their faces were so distinctive that I had to wonder if they were modelled after real people.

We headed over to the river for a quick view, although oddly enough the state park is not very close to where the actual three islands are.

return • continue