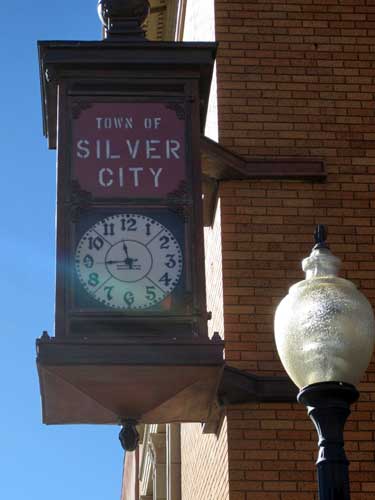

We had a nice, slow morning. Our evening destination was Chiricahua National Monument, but we were in no hurry. We first wandered around the old, historic downtown of Silver City.

Originally, this land was home to the Mimbres group of the Mogollon culture from the year 200 to around 1150. The Apaches arrived in the late 1500's. Spanish and then Mexican settlements made brief appearances. In 1870, silver was discovered nearby, and the small settlement of Ciénega de San Vicente (the Marsh of St. Vincent) changed into Silver City as prospectors poured into the area.

The town was designed with the streets running north to south... directly in the path of the sumer rain runoff. High sidewalks were built in the downtown area to accommodate these regular flood waters. Meanwhile, uncontrolled cattle grazing as well as deforestation thinned the plant life on the surrounding hills. During July 21, 1895, a flood rushed through the downtown business district, turning Main Street into a giant ditch, 55 feet lower than its original level. These businesses had to start using their back doors as main entrances, which eventually became the permanent new front entrances.

High sidewalks indeed! This curb was at least 2 feet tall! If you parked too close to it, you wouldn't be able to open the car door!

Silver City Municipal Court

City Hall

Images of New Mexico... a Yucca plant in bloom and the Zia sun symbol, the image on the state flag which was inspired by a design found on a 19th century water jar from the Zia Pueblo.

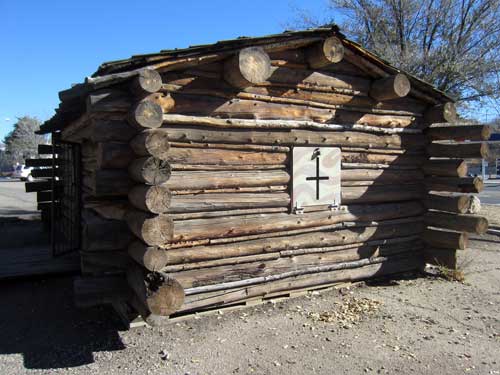

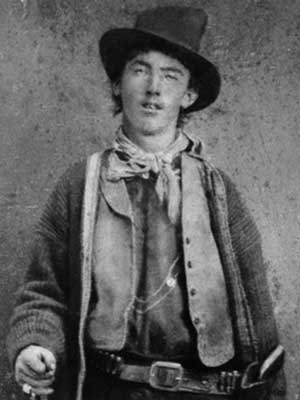

Billy the Kid lived in a small log house with his mother and stepfather on this location from 1873 to 1875. The original cabin was torn down in 1894.

Henry McCarty (also known as William H. Bonney and Billy the Kid) was born in 1859. His father died shortly after the birth of the family's third child. He moved, along with his mother and siblings, to Kansas with Henry Antrim in 1870. His mother married Antrim in 1873 in Santa Fe. Shortly after, they moved to Silver City where she died of tuberculosis in 1874.

Billy had his first run-in with the law (for theft) a year after his mother's death and a day before his 16th birthday. After that, he moved about, working on ranches and spending time in local gaming houses. Eventually he turned to horse thieving, stealing from local soldiers. In 1877, he killed his first man during an altercation in Arizona. He fled to New Mexico where he joined a band of cattle rustlers. From then on, he seemed to get tangled up with numerous shootouts, causing him to be wanted by the law... which he eluded quite well.

In 1880, he was captured by Pat Garrett. Billy went to trial in 1881 and was sentenced to hang. While he was in jail one night with only a deputy on guard, Billy asked to use the outhouse. On their way back, Billy slipped out of his handcuffs and attacked the deputy, eventually getting his revolver and shooting him in the back as he attempted to get away. With his legs still shackled, Billy got a loaded shotgun and killed another deputy who was responding to the gunshot. He freed himself from the leg irons using an axe, stole a horse and rode out of town.

Almost three months after his escape, Garrett caught up with him, fatally shooting him just above his heart. In the weeks following his death, however, people had begun to talk about it being an unfair encounter. In response, Garrett had a book published, highlighting Billy's life and bringing him the fame that he hadn't really had while alive.

Henry McCarty (1859 - 1881) was known as The Kid because of his youthful appearance. According to legend, he killed 21 men, but it is now generally believed he killed eight.

We began our journey toward the Arizona border, stopping briefly in the Lordsburg visitor center. There we learned about the nearby ghost town of Shakespeare. Unfortunately, it wasn't open today (apparently there are safety concerns so one can only enter on a guided tour). But I did learn about one of the town's more colorful stories:

"The Strange Hanging of Arkansas Black"

In the Old West, men were often hanged for murder, cattle rustling and horse theft. One man, however, was actually hanged THREE times for the crime of romance. Robert "Arkansas" Black was a saloon owner. He was well liked by everyone in town... particularly the womenfolk. That was all well and good until he took up with a married woman. Such goings-ons were hard to conceal in such a small town, and soon the other married women were demanding that their husbands do something about it.

So one night, a group of the married men met with Arkansas and told him he had to leave town. Arkansas grabbed for his pistol but was subdued. They tied him up, brought him to the center of town, and hanged him from the crossbeam of a corral gate. After they realized it was not killing him, the lowered him down and once again told him to leave town. Once again, he profanely refused. So they hoisted him up again.

The third time they tried to hang him, he passed out... but still didn't die! They lowered him again and revived him by means of a bucket of water. In reply to their demands to leave town yet again, he offered to kill them all in a fair duel if they would return his gun to him.

Not knowing what to do, they were about to hang him a forth time, when another saloon owner walked over and suggested that since Arkansas was so popular, perhaps they should run the woman out of town instead. And so, the woman and her husband promptly left town the next morning after receiving a threatening visit.

We turned off the main highway, taking a shorter route to Chiricahua, when we saw signs for Fort Bowie (pronounced Boo-ee) National Historic Site. So we decided to check it out. The last bit of the road was quite rocky!

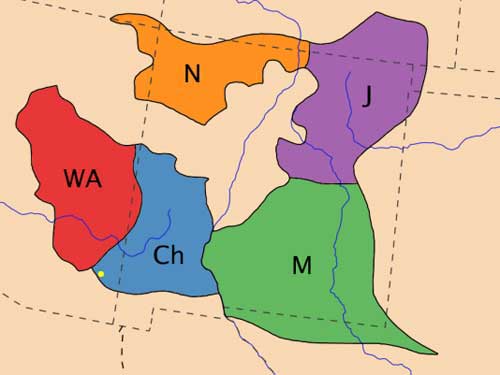

Early history: The Apachean and Navajo peoples were part of the Athabaskan migration across the Bering Strait from Siberia into North American. As they moved south and east, groups splintered off and became differentiated by language and culture over time. Some anthropologists believe the Apache and Navajo were pushed into New Mexico and Arizona by pressure from other Great Plains Indians, such as the Comanche and Kiowa. Among the last of such splits were those that resulted in the formation of the different Apachean tribes. This area was home to the Chiricahua Apaches for hundreds of years.

Apachean tribes in the 18th century: Western Apache (WA), Navajo (N), Chiricahua (Ch), M Mescalero (M), Jicarilla (J). The yellow dot is where we are now.

1849: A low divide separated the massive Chiricahua Mountains from the Dos Cabezas Mountains. It was a rugged corridor through which people and goods were moved. The Spaniards called it Puerto del Dado (the Pass of Chance); we know it as Apache Pass. Because it contained critical supplies for travelers and their animals... wood, grass, water in the form of a reliable spring... the attracted many emigrants, prospectors and soldiers into this Apache homeland. The first established wheeled transport through the pass began in 1849 with the California Gold Rush. This was the shortest and most direct route.

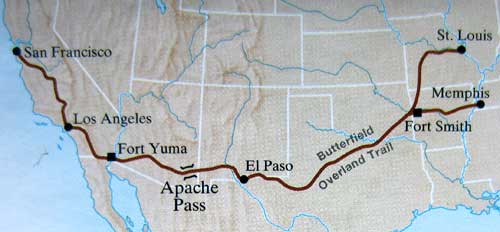

1858: Created by John Butterfield, the Overland Mail Company started its operation with about 2,000 employees, over 250 coaches, several hundred wagons, 1,800 horse and mules, and 240 stage stations along its 2,800-mile route. The government paid the company $600,000 per year for carrying mail. In its 3-year history, it was only attacked once by Apaches.

The route of the Overland Mail Company, which was to be covered in only 25 days

1861: In January, a band of Coyotaros Apaches raided the ranch of John Ward, stole some livestock, and kidnapped the half-Apache 12-year-old son of a Mexican woman who lived there. Ward wrongfully believed it was a Chiricahua Apache named Cochise. Cochise was working as a woodcutter at the Butterfield Overland stagecoach station.

In February, an inexperienced army officer, Lieutenant George Nicholas Bascom, arrived with 54 calvarymen. Under false pretenses, he lured Cochise to his tent. Cochise arrived with his brother, wife (Dos-teh-seh, meaning "Something-at-the-campfire-already-cooked"), youngest son and two other warriors... clearly expecting some sort of social call. Cochise was entirely unaware of the kidnapping, and when he claimed innocence (which he actually was), Bascom ordered his men to seize them with the plan to hold them as prisoners until all property (including the boy) was returned. In the ensuing struggle, one Apache was killed and four others were subdued. Cochise escaped but was shot three times.

In order to put himself in a negotiating position, Cochise promptly abducted several prisoners of his own (first a Butterfield stagecoach stationmaster named Wallace, and later three white men seized from wagons en route to the mines at Pinos Altos) to exchange for the Apache captives. Things continued to escalate... more calvary arrived, bringing three other Apaches captured from completely different tribes... more skirmishes... Cochise tortures, kills and mutilates his captives, spreading the body parts about (Wallace was identified only by the gold fillings in his teeth). In retaliation, Bascom hangs six Apaches... sparing Cochise's wife and son, but including his brother. This whole 'Bascom Affair' ignited a violent rampage of death and destruction that would rage for the next 10 years.

Eyewitness account by Sergeant Daniel Robinson, Seventh Infantry: After witnessing the fiendish acts committed by the Apaches, the minds of our officers and men were filled with horror, and in retaliation, it was decided in Council, that the captive Indians should die. On the 19th we broke camp to return to our respective posts leaving a Sergeant and eight men to take charge of the station until relieved. We halted about half a mile from the station where there was a little grove of Cedar trees. The Indians were brought to the front with their hands tied behind their backs, and led up to the trees. Noosed picket ropes were placed around their necks, the ends thrown over the limbs of the trees and manned by an equal number of willing hands. A signal was given and away flew the spirits of the unfortunate Indians - not to the happy hunting grounds of Indian tradition. According to their ideas or belief in a hereafter, those who die by hanging can never reach that region of bliss. I was in an ambulance with the other Sergeant, and must confess it was a sad spectacle to look upon. An illustration of the Indians sense of Justice: “That the innocent must suffer for the guilty.” And the white man’s notion -“That the only good Indians are dead ones.” Whatever it may be, I do not think it was much worse than the present policy of penning them up on Reservations and starving them to death.

Cochise (1824? - 1874). There is no authentic likeness of him known to exist, only portraits based on written descriptions and facial features based on his sons.

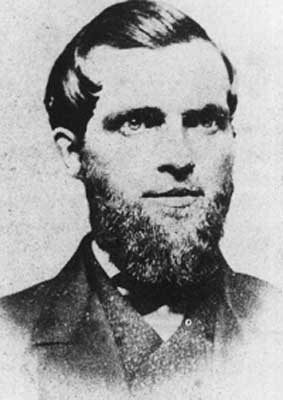

Lt. Bascom (1837 -1862) was killed in a Civil War engagement the following year.

Felix Telles/Ward (1848/51 - 1913/15) was the boy who was abducted. It was unclear who his father was... some say he was part Irish but others think it was an Apache who had kidnapped his mother. Either way, he was never returned home. He was raised to become a warrior by different Apache tribes. He resurfaced in 1872 as an Apache scout and interpreter at Camp Verde, where the soldiers gave him the nickname Mickey Free, after an Irish character in Charles Lever’s popular 1841 book Charles O’Malley, the Irish Dragoon. They often assigned comical names to the Apaches.

1862: In July, an army of 3,000 California volunteers under Brigadier General James Henry Carleton was on its way to New Mexico where they were to establish a supply depot for Union forces and to confront Confederate troops. They were ambushed by Cochise at Apache Pass.

About one week later, construction of a fort was started by soldiers from the 5th Regiment California Volunteer Infantry. Named after their commanding officer, Colonel George Washington Bowie, it was completed in less than 3 weeks... although at this point it was little more than a temporary camp. As winter approached, tents were replaced by crude stone and adobe huts.

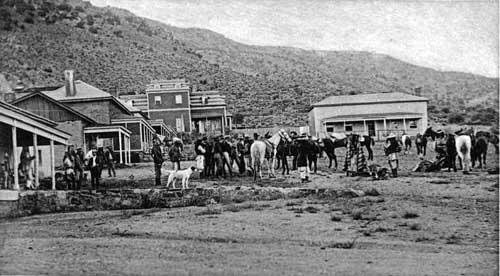

1868: A second, more substantial fort was built which included adobe barracks, houses for officers, corrals, a trading post, and a hospital. More buildings were added over the years, eventually reaching around 38 structures. It provided calvary escorts for travelers, mail couriers and freight wagon supply trains.

Fort Bowie. Click for a larger view

1861 - 1871: Cochise and 200 followers eluded capture for more than 10 years by hiding out in the Dragoon Mountains, from which they continued their raids, always fading back into their mountain strongholds. The fort was the center for military campaigns against them.

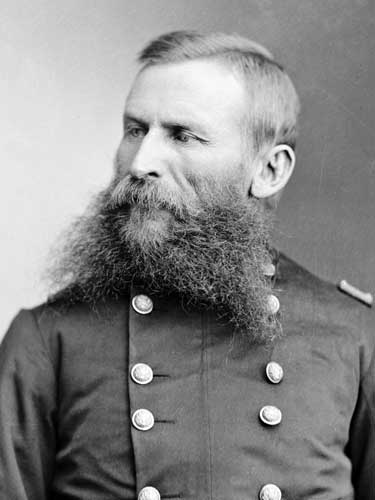

1871: Lieutenant Colonel George F. Crook, commander of the Department of Arizona, succeeded in winning the allegiance of a number of Apaches as scouts (including Mickey Free). Cochise resisted transferring his people to the Tularosa Reservation in New Mexico.

General Crook (1830 - 1890)

1872: Cochise finally surrendered when the Chiricahua Reservation was established. He and his people were moved to the 3,000 square mile reservation nearby that included some of their traditional homeland.

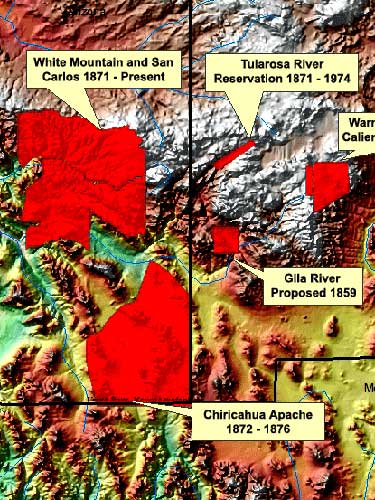

The various reservations

1874: Cochise died of natural causes (probably abdominal cancer) and was buried in the rocks above one of his favorite camps in the Dragoon Mountains, now called Cochise Stronghold. The younger Apache began to grow discontented with their conditions on the reservation.

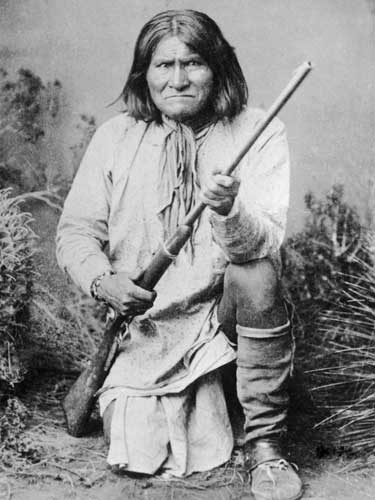

1876: In an effort to impose more rigid control, the government abolished the reservation and moved some 4,000 Apaches to the barren wasteland of San Carlos Reservation far away in the Gila River Valley. Deprived of traditional tribal rights, short on rations and homesick, they revolted. Several bands led by Geronimo and others fled to Northern Mexico and began to terrorize the border region.

Geronimo (Goyahkla, "The one who yawns", 1829 - 1909) in 1887. While never officially a chief, he was a prominent leader of the Bedonkohe Apache who continued to fight for his homeland after Cochise's death.

Geronimo was born near the Gila River. His grandfather had been chief of the Bedonkohe Apache. He married when he was 17 and had three children. In March 1851, however, 400 Mexican soldiers attacked his camp while the men were in town trading. They killed his mother, wife and children. This began his hatred for Mexicans for the rest of his life and he joined with Cochise to help with his revenge. This is where his name of Geronimo came about. During one battle, his attack using nothing but a knife was so fierce that the Mexican soldiers were heard shouting something. It is believed they were pleading to Saint Jerome for help... Jeronimo! The name is synonymous today with extreme courage and heroism to the point of complete disregard for one's own personal safety.

It's unclear exactly how many wives he had over the course of his life although it is believed to be nine. In times of war, it was considered appropriate by the Apache to marry quickly and often. According to Geronimo, he always had at least two wives at a time, and at one point even three. Because his wives were known by both their Apache and English names (and the Apache names are often misspelled), it's difficult to determine the exact order and overlapping of his marriages. We know his first wife was killed; his second was taken by Mexicans and a third was killed along with their child by Mexican troops. One died of tuberculosis while held in captivity in Florida; others disappeared while in captivity or during transportation. Geronimo had around eleven children, although only a few survived to adulthood.

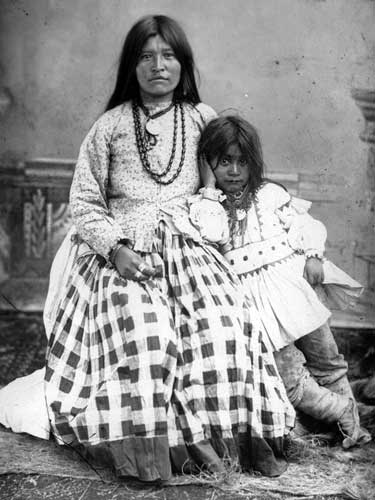

One of his wives, Ta-ayz-slath. At Fort Bowie, she and her son awaited removal (without Geronimo) on a nightmarish train ride to Florida.

His fourth wife Marionetta or She Gha (Early Morning), their two-year-old son "Little Robe"(who died at Fort Bowie) and Dohn-say (Geronimo's daughter from his second wife who was taken by Mexicans). Both Marionetta and Taz-ays-slath disappeared from all records between Florida and Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

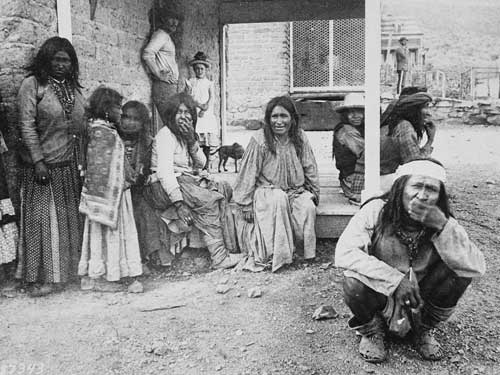

1876 - 1886: During the next 10 years, many Apache were captured and returned to the reservation... where they would promptly escape again. Not only did the people, who had lived as semi-nomads for generations, dislike the restrictive reservation system, but captivity was a hell of dying children and sick adults. Spectators, hoping to see a "war dance," did not understand that the Apaches danced and prayed for the lives of their children.

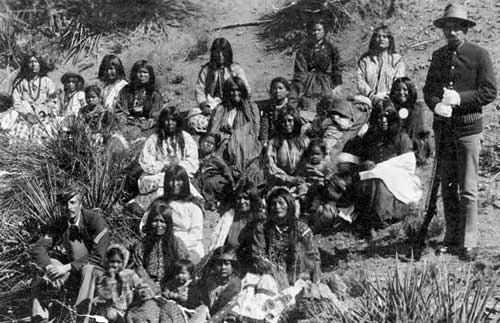

Apache prisoners at Fort Bowie, 1884

1886: The last escape occurred in 1885 when Geronimo and several other leaders, accompanied by 35 men, 8 boys and 101 women, fled the reservation to Mexico. After being pursued by at least 5,000 white soldiers and 500 Indian auxiliaries (including Mickey Free) for five months and 1,645 miles, Geronimo and his followers were worn down, having had little or no time to rest or stay in one place. Camped on the Mexican side of the border, Geronimo agreed to General Crook's surrender terms. However, fearing that they would be murdered once they crossed back into US territory, Geronimo and some of his followers bolted. Finally in 1886, almost a year after the chase had begun, Geronimo surrendered once again after being promised that after a short exile in Florida, he and his followers would be permitted to return to Arizona.

The promise was never kept. Geronimo and other Apaches (including scouts who had helped the army track him down) were brought to Fort Bowie and taken in wagons to the railroad for their exile to Florida. He wasn't even sent to the same fort as his family. Eventually in 1887 they were reunited and transferred to Alabama for 7 years, after which they were moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. He never saw Arizona again.

The captive wives and children of the Apache leaders and warriors Chihuahua, Geronimo, Perico, Bische and Mangus at Fort Bowie in April 1886. It was concern for these families that drove the men to surrender in 1886. Within hours of sitting for their photographs, the unsuspecting women and children were sent into 27 years of captivity and exile.

Geronimo departing for Florida from Fort Bowie

1894: With the end of Apache wars, the fort's usefulness as a military installation. Eventually it was abandoned.

1972: The fort is protected as a historic national site comprising on 1,000 acres.

Click for a larger view

We set out for the fort, with many interesting and informative stops along the way.

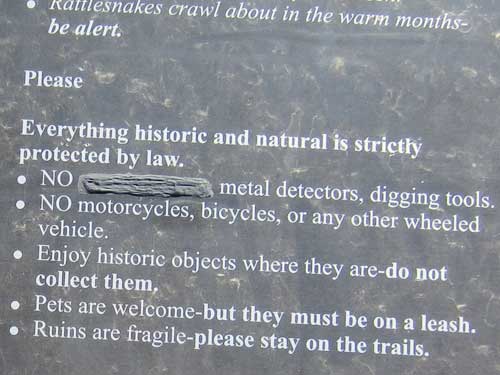

I wonder what was blotted out!