It was a mile and half hike out to the ruins of the old fort. The original route was a wagon road created by the soldiers who garrisoned the post. The trail today basically follows the old military road.

The hills lie within the Upper Sonoran life zone, with desert grasslands on the lower slopes rising up to chaparral with tough evergreens; oak, juniper and pinyon pine on the higher slopes; willow, walnut and cottonwood along the drainages.

These are the ruins of the cabin of prospector Jesse L. Millsap (1863 - 1929). Millsap, 65 years old, was being hoisted up from the bottom of a 125-foot well. He had gone down to set some dynamite. He was only 10 feet from the top when a knot in the rope slipped, hurtling him back down. He was killed instantly. His head was crushed and his legs were broken... and then the dynamite charges he had set went off.

Mining in Apache Pass started in 1864 with the discovery of gold with the Harris Lode. With the expansion of Fort Bowie in 1877, mining activity in this area became illegal. It became popular again in the early 1900's.

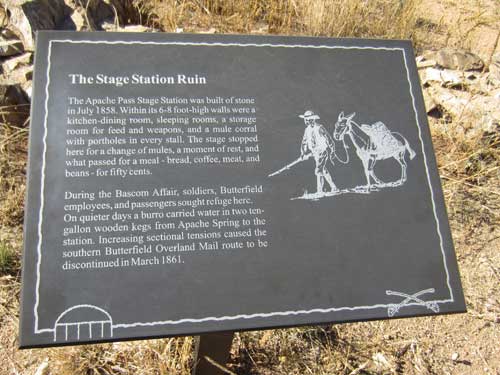

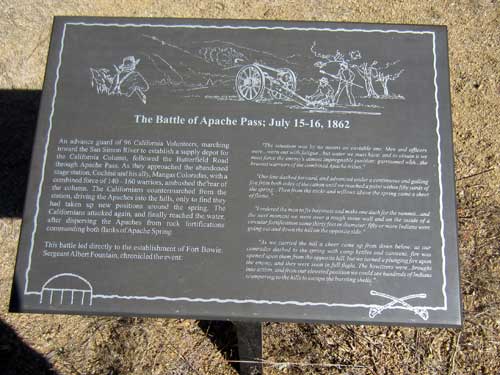

Numerous informative signs lined the way.

Ruins from the old Butterfield stage station

The Apache Pass Stage Station was built of stone in July 1858. It had high walls (6 - 8 feet), a kitchen/dining room, sleeping rooms, a storage room for feed and weapons, and a mule corral. Before the Bascom Affair, they paid Cochise and his people to supply the station with wood. After the southern section of the route was discontinued on the Civil War in 1861, the station was abandoned.

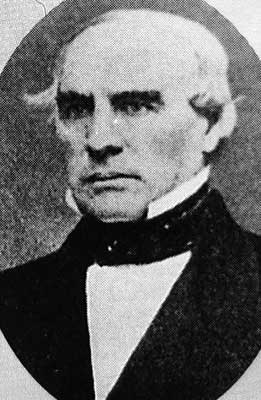

John Butterfield, founder of the Overland Mail Company

The Celerity Wagon was fast and light weight, specially designed for this rugged portion of the Butterfield Overland stage route.

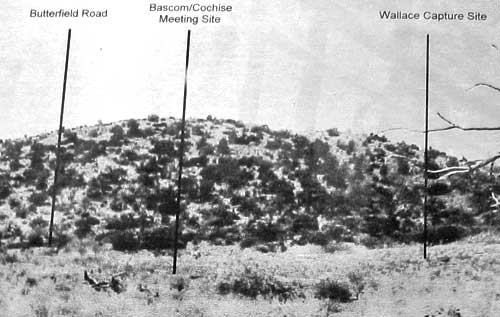

Location of the Bascom Affair of 1861

Another excerpt from Sergeant Daniel Robinson:

Our wagons were placed end to end, forming a semicircle, covering one side of the station, and the corral, making a basis for outer breastworks. There was a deep ravine on this side, the head or nearest point of it about a hundred yards from the station. Empty grain sacks were filled with earth and placed on the inner side of the circle. …the Apaches were assembling in force on a hill 800 yards off.

The ‘talk’ commenced by Cochise making a strong appeal for the release of the … captive Indians. He was told that they would not be released until the boy was given up or found … In this manner the talk continued for about an hour.

[Butterfield employee James] Wallace approached the ravine at a point above us apparently unnoticed by anyone … A dash was made by a few Indians from the ravine. They seized and dragged him into it out of sight. This broke up the talk in quick time.

Continuing on

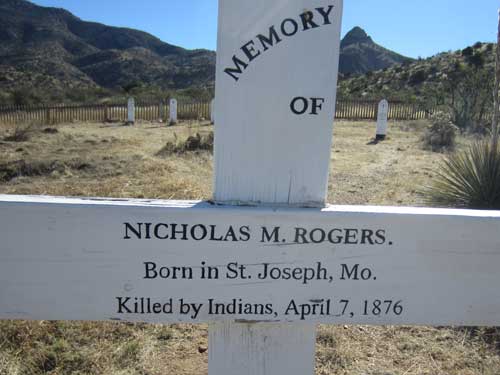

The Post Cemetery predated the establishment of the fort, when soldiers of the California Column were buried here in 1862. The area was unfenced until 1878 but then a wall was built to protect the graves from desecration by livestock. In 1885, a fence replaced the wall and by 1887, headstones replaced the wooden headboards. There were soldiers and the families, civilian employees, immigrants, mail carriers and three Apache children. The final burial, brining the number up to 112 graves, was of a murdered miner. Five months after the fort's closure, 72 soldiers and their family members were removed for reinternment at the San Francisco National Cemetery. It is thought that 23 to 33 bodies remain.

When the National Park acquired the cemetery in 1964, there were only two original headboards remaining... and the inscriptions on both of them had completely weathered away. Replacements for some of them were based on historic photographs; others were based on written descriptions from a newspaper reporter who visited in 1886. The fence was rebuilt in 1989.

Julian Aqueira: a 46-year-old mail rider, killed en route by Apaches in 1871

H.B. Elliot: a 35-year-old with tuberculosis en route to medical treatment. He began hemorrhaging in his lungs upon arrival at the fort in 1875

Juan Frentes: a 56-year-old Mexican-born post trader, died of chronic pneumonia in 1875

Milton Sage: a 32-year-old scout and military man, died of pneumonia in 1884

Litte Robe: the 2-year-old son of Geronimo and Marionetta (or She Gha). This was clearly a name given to him by someone at the fort. He was part of a group of Apache prisoners (7 women and 8 children... 2 were Geronimo's wives and 2 were his sons) captured in 1885. Little Robe died probably of dysentery, and the soldiers of fort buried him here. While the marker still remains, the body has been removed. Traditionally, Apaches buried their dead by sealing them in small caves or crevices or by placing them in natural depressions, with the heads pointing toward sundown. Burials were concealed by covering them to blend with the environment. Their locations were usually not marked.

S. Merejildo Grijalva: a 5-month-old born at Fort Bowie but died of unknown causes in 1872. The child's father was an army scout who had been raised as an Apache captive.

Unknown Apache Child: died of dysentery two weeks after Little Robe in 1885

The three young children

Pedro Veldez: a Mexican native who worked at the fort, died of pneumonia in 1887

John Slater: a 35-year-old infantry man and US mail carrier, killed by Apache ambush in 1867

Nicholas Rogers and Orisobo Spence: 28-year-old Rogers ran the mail stage station at Sulphur Springs and had a habit of selling whiskey to the Apaches on the reservation. 33-year-old Spence worked as a cook for Rogers. In 1876, Rogers had sold some whiskey to some Apaches. When they came back a few days later for more, he refused, and both men got killed.

Spence received the Medal of Honor for gallantry in action in a fight against Cochise in 1869

James F Walker: a 6-year-old, accidentally run over by a wagon in 1867

J.G. Duncan: a 34-year-old captain of the Union army, died of tuberculosis in 1870

John McWilliams: the 26-year-old quit working for the mail because the job was too dangerous, took a job as a cattle herder for a beef contractor. Unfortunately the herd was attacked by Apaches in 1872 and he was killed.

J.B. Fletcher: unknown citizen who died in the hospital of unknown causes in 1880

Leonardo Orosco: a 20-year-old teamster who ran the fort's trading store, died suddenly in 1880

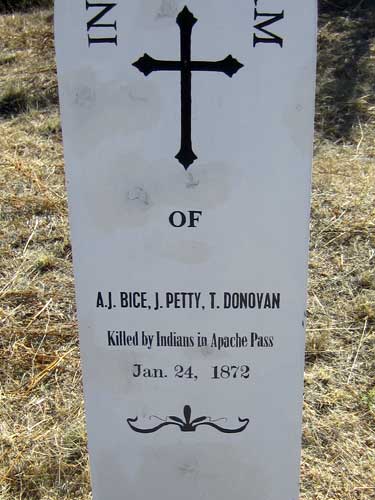

Aaron J Bice, John Petty and Thomas Donovan: this grave contains all three of their remains. Bice and 42-year-old Petty were killed by Apaches heading with the west-bound mail; Irish immigrant Donovan was killed while en route with the eastbound mail on the same day in 1872. Donovan's partner was injured but survived.

Marcia Ju: among the first group of Apache prisoners (3 women, 8 children) brought to Fort Bowie. She was probably already sick and died a day later in 1885.

John Brownley: a 25-year-old teamster on a mail coach, killed during an Apache attack in 1868. The 3 other men on the coach were captured and later killed.

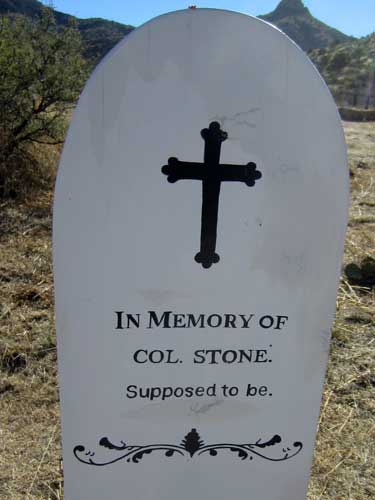

John Finkle Stone: a 33-year-old enlisted in the infantry who helped develop the Harris Lode mine, killed by Apaches near Dragoon Springs along with 5 other people on the stagecoach in 1869

The term "supposed to be" was used when the condition of the body or the lack of identification of the grave left cause for doubt as to the actual person buried there.

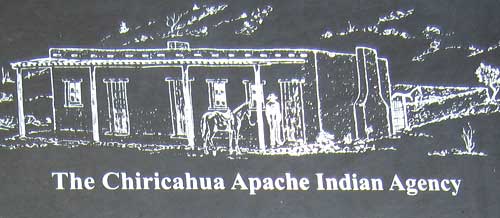

US Indian Agent Thomas Jeffords governed some 900 Chiricahua Apaches here in 1875 - 76, under the vigilance of the US Army at Fort Bowie. After Cochise died and unrest began to increase, Jeffords was removed and 325 Apaches were transferred to the San Carlos Reservation.

The position of "Indian agent" first appeared in 1793. Legislation allowed the appointing of persons, from time to time, as agents to reside among the Indians, and guide them into forced acculturation of white American society by changing their agricultural practices and domestic activities.

From the 1800's to late 1820's, duties included:

- Work toward preventing conflicts between settlers and Indians

- Keep an eye out for violations of intercourse laws and to report them

- Maintain flexible cooperation with US Army military personnel

- See to the proper distribution of annuities granted by the state or federal government to various Indian tribes

- See to the successful removal of tribes from areas procured for settlement to reservations

In the 1830's, the primary role of Indian agents was to assist in commercial trading supervision between white traders and Indians.

By the 1870's, the average Indian agent was primarily nominated by various Christian denominations. Part of their belief was that civilization can only be possible when Indians cease communal living in favor for private ownership.

In the 1880's, job duties were:

- Induce his Indian to labor in civilized pursuits and absolutely no work must be given to white men which can be done by Indians

- See to it that the Indians under one's jurisdiction can farm successfully and solely for the subsistence of their respective family

- Enforce prohibition of liquor

- Provide the instruction of English education and industrial training for Indian children

- Allow Indians to leave the reservation only if they have acquired a permit for such

- Compile an annual report of his reservation with the following information: Indian name, English name, Relationship, Sex, and other statistical information

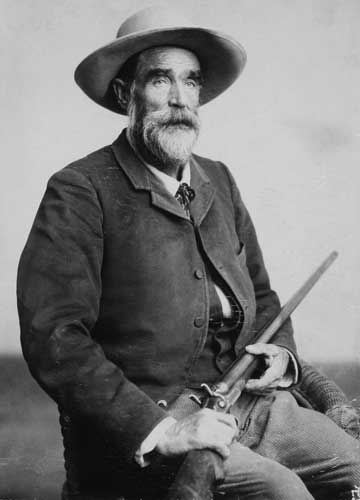

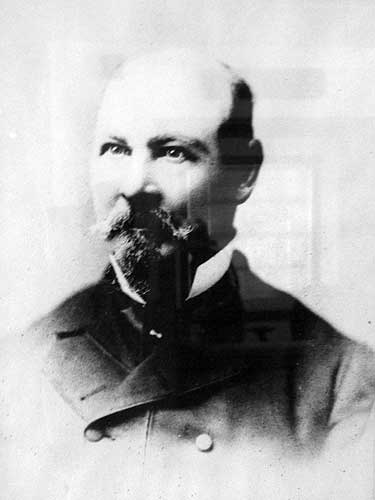

This is the only known portrait of Thomas Jonathan Jeffords (1832 - 1914) from 1895.

Jeffords was born in New York in 1832 and moved steadily westward, compiling a variety of occupations... mining, army scout, and later deputy sheriff in Tombstone and a stagecoach driver in the Arizona Territory. He married an Apache girl named Morning Star, but unfortunately she was killed in a raid shortly thereafter.

During his job as superintendent of a mail line that later became part of the Pony Express, some of his mail riders were killed by Apache raiding parties. Jeffords rode out alone to Cochise's camp to talk. This bravery so impressed the chief that they became friends. It was this friendship that helped end the Apache wars in a treaty between Cochise and General Oliver Howard in 1872. Cochise requested that his people be allowed to remain in the Chiricahua Mountains (creating the Chiricahua Reservation) and that Jeffords be made Indian agent for the region. Both requests were granted.

Certain white residents of the area disapproved of this arrangement because it denied them access to the copper and silver that had been discovered on Apache lands. They called Jeffords an “Indian lover” and wrote scathing reports to politicians back in Washington. By this time, Cochise had died and there was unrest in the reservation. Jeffords was removed as the federal agent in 1876 and the Chiricahua Apaches were relocated to the San Carlos Reservation, promplty ending the original conditions of Cochise's treaty.

These ruins of the old agency were excavated in 1984. There were three rooms, each with fireplaces and wooden floors. It probably had a porch in front and a corral in back. It would have had a flat roof and small windows.

Location of the Battle of Apache Pass

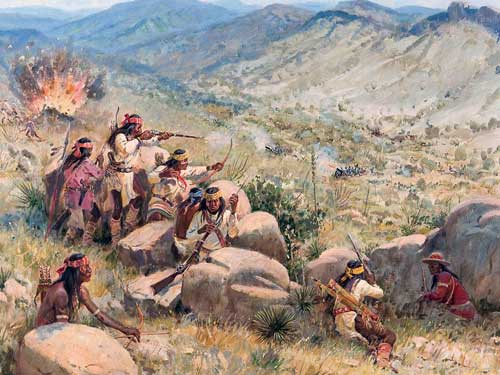

In 1862, an advance guard comprised of 96 California Volunteers marched through Apache Pass on their way to establish a supply depot. As they approached the abandoned stage station, Cochise and about 150 warriors ambushed the rear of the column. The Californians countermarched from the station, driving the Apache into the hills, only to find they had taken up new positions around the Apache Spring. The Californians attacked again, and finally reached the water, after dispersing the Apache from rock fortifications commanding both flanks of the spring. This battle led directly to the establishment of Fort Bowie.

Painting by Joe Beeler (1931 - 2006)

Sergeant Albert Fountain wrote of the event:

The situation was by no means an enviable one. Men and officers were worn out with fatigue ... but water we must have, and to obtain it we must force the enemy's almost impregnable position: garrisoned with the bravest warriors of the combined Apache tribes. Our line dashed forward, and advanced under a continuous and galling fire from both sides of the canyon until we reached a point within fifty yards of the spring. Then from the rocks and willows above the spring came a sheet of flame.

I ordered the men to fix bayonets and make one dash for the summit and the next moment we were over a rough stone wall and on the inside of a circular fortification some thirty feet in diameter; fifty or more Indians were going out and down the hill on the opposite side. As we carried the hill a cheer came up from down below, as our comrades dashed to the spring with camp kettles and canteens. Then fire was opened upon them from the opposite hill, but we turned a plunging fire upon the enemy, and they were soon full flight. The howitzers were brought into action, and from our elevated position we could see hundreds of Indians scampering to the hills to escape the bursting shells.

Painting by Francis Beaugureau (1920 - 2001) with a 12-pound mountain howitzer

Next we arrived at a recreation of an Apache home. A camp usually considered of several thatched wickiups clustered together and hidden for safety. The camps were not permanent. Low food supplies or discovery by an enemy forced the Apache to move frequently.

Camp life centered around the wife's extended family. At marriage, the husband entered into the family and took responsibility for supporting her relatives. Men hunted and raided; women harvested and took care of the crops. Food was shared in the community and surpluses were stored.

A wickiup consisted of a simple pole framework covered with beargrass and animal hides.

Native Americans had many different styles of housing. Each tribe needed something that would fit their lifestyle (nomadic hunters, permanent agricultural), location (desert, forest, arctic, swamp, etc) and climate.

WICKIUP - domed dwelling in the Southwest US; temporary; could be assembled quickly from materials easy to find in the environment.

WIGWAM (also wetu or birchbark houses) - domed dwelling in the Northeast US and Canada; woodland regions; wooden frames covered with sheets of birchbark; good for staying in the same place for months at a time; not portable but are small and easy to build; could hold up to bad weather.

TIPI (or Teepee) - tent-like dwelling used by Plains tribes; cone-shaped wooden frame with a buffalo hide covering; designed to set up and break down quickly; transportable to follow the buffalo herds; with few trees on the Great Plains, it was important to carry the long poles with them.

CHICKEES (stilt houses or platform dwellings) - an elevated platform several feet off the ground supported by thick posts with no walls and a thatched roof; used primarily in Florida in hot, swampy climates; the long posts kept the house from sinking into the marshy ground; a raised floor kept animals like snakes out; walls were not needed since it didn't get cold.

PUEBLOS (adobe houses) - multi-story houses made of adobe (clay and straw baked into hard bricks) in the Southwest; each unit was a home for one family; the whole structure could contain dozens of units.

KIICHA - cone-shaped hut of willow branches covered with brush or leaves; in California; temporary shelter for sleeping or as refuge in bad weather; when a dwelling reached the end of its practical life it was simply burned and a replacement made in about a day's time.

EARTHEN HOUSE (Navajo hogan, Sioux earth lodge, subarctic sod house, pit house of the West Coast) - semi-subterranean dwelling dug from the earth with a domed mound over the top (usually a wooden frame covered with earth or reeds); permanent home in non-forested areas; good in harsh climates with protection from wind and strong weather.

ASI (wattle and daub houses) - used by Southeastern tribes; made by weaving rivercane, wood and vines into a frame then coating it with plaster; roof was either thatched with grass or shingled with bark; permanent structure that took a lot of effort to build; required a fairly warm climate to dry the plaster.

GRASS HOUSE - domed dwelling thatched with prairie grass; used by Southern Plains tribes; good for warm climates.

LONGHOUSE - similar to wigwams just much larger (up to 200 feet long, 20 feet wide, 20 feet high); in the Northeast US and Canada; raised platforms created a second story; mats and wood screens divided it into separate rooms; could house up to 60 people; permanent dwelling; took a lot of time to build and decorate.

A piece of mysterious material found nearby

Pottery fragments found around Apache Spring suggest it was used by Mogollon tribes long before the Apache arrived. The Butterfield Trail was built through Apache Pass simply because of this reliable water source. If this water had not been here, there probably wouldn't have been all the wars, or a stage station, or even the fort.

The second Fort Bowie (left) and the first Fort Bowie

Aerial view of: 1 - old fort; 2 - Apache Spring; 3 - second fort

The ruins from the first Fort Bowie, built in 1862. It was basically a 4-foot-high stone wall surrounded a collection of tents and a stone guardhouse. While the Apaches no longer controlled the spring, the did continue raiding and killing travelers not escorted by the military.

It was an undesirable place to be... isolation, bad food, sickness, crude quarters, stress from seldom-seen but ever-present Apaches, low morale, frequent troop rotation. In 1866, regular soldiers arrived to relieve the California volunteers, and in 1868, the new larger fort was finished.

We arrived at the ranger station and took a look around. The woman working there wasn't a ranger but rather the wife of the ranger. He had gotten called away to Chiricahua National Monument... which is where we were headed next. We asked if she could call over and help us make a quick reservation since tomorrow was a holiday and we were concerned things might already be all booked up. Unfortunately no one was answering, not even her husband. So we were just going to have to wing it.

Naiche, Cochise's youngest son, who supposedly strongly resembles his father

George Washington Bowie (pronounced Boo-ee), after whom the fort is named

Albert Jennings Fountain, a sergeant in the California Column who wrote one of the most accurate accounts of the Battle of Apache Pass

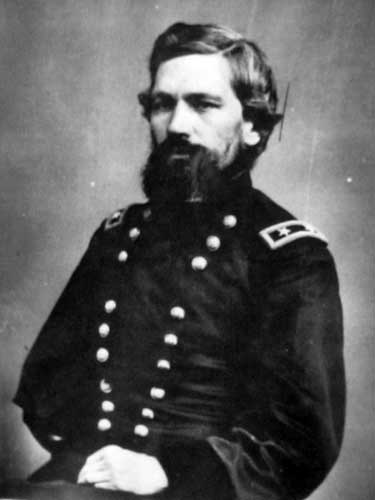

General O.O. Howard, the one-armed general who, together with Tom Jeffords, negotiated peace with Cochise in 1872

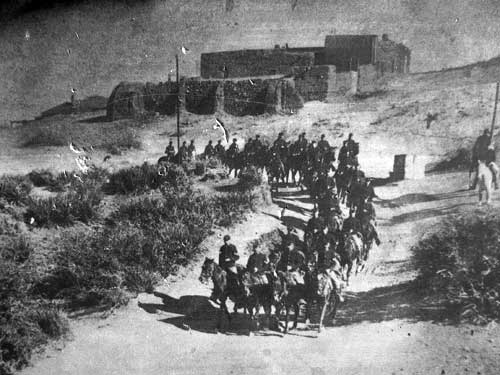

Riding out from the fort

Negotiations

1862 uniform of a 5th Regiment California Volunteer Infantry

Dress parades were held every day at sundown and for special occasions (such as visits from high-ranking officials). Roll call was held and assignments were given. This is the uniform of a 6th Calvary sergeant from 1881.

Women on the frontier

Army regulations of the era required that only single men be enlisted in service. Soldiers were allowed to marry later provided the company commander granted consent. Most captains, however, attempted to discourage their men from assuming the burden of a wife on a soldier's pay, which in the 1880's was $13 per month for a private. Even once married, the army refused to recognize the wives, denying them government quarters... which was especially difficult if the the company commander denied the soldier the privilege of residing out of quarters.

The only women officially recognized by the army were company laundresses. Maintaining soldiers' clothing was considered a military necessity. They were always in high demand as wives and seldom remained single very long. Such women possessed their own quarters, income and rations... and she could live near her husband no matter where he was stationed.

Then the rules changed. In 1878, Congress decided they had become an expensive luxury. They were no longer seen as part of the army. Married laundresses were exempted until their husbands' current enlistment ended. But she no longer got government housing or pay. That said, there was no law forbidding women to work and get paid as civilians doing the laundry. This change was seen at Fort Bowie, where within two years of the rule, the number of laundresses dropped from seven to just one. By then, two Chinese laundrymen had set up shop nearby to fill the void.

Besides laundering, prostitution was one of the few occupations open to women in the environs of the fort. These "women of bad character" were available at the stage station as well as at a few saloons within a couple miles of the fort. In spite of the commanding officer's attempt to drive these places out of business, their doors only closed once the fort was gone.

Items found around the fort...

... including Captain Roberts' false teeth. Apparently a packrat had stolen them from his bedside in the 1880's. They were found about 100 years later!

Apache items

The Sibley Stove, patented in 1858. Inspired by a visit to a Comanche tipi, Major Henry H. Sibley invented a tent and a stove for use by the US Army. He was to receive a royalty for every tent and stove manufactured. During the Civil War, the Union army used 43,958 of his tents and 16,000 of his stoves. Unfortunately, Sibley fought on the Confederate side... so he never received a single penny, which would have added up to $250,000 in royalties.