When we got up in the morning, the water had frozen in a gallon jug we had left outside. Fortunately the sun was out. We went and soaked for a while in another set of pools on the other side of the resort.

A life of leisure

I believe the 'hot' was 105 degrees F or so.

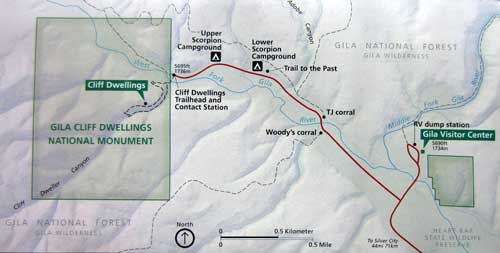

It was a long and very twisty drive up to Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument.

We arrived at the visitor center but were told a ranger tour was just about to begin. So we hopped back in the car and raced over to the actual dwelling site.

The visitor center

The first non-native person to become aware of the ruins was H.B. Ailman, who was out on a prospecting trip in 1878. By the time archeologist Adolph Bandelier arrived in 1884, looters had already stolen many artifacts and destroyed much of the archeological record. Settlement of the region increased after the Apache wars ended in 1886. They carved out mines, raised cattle and sheep, and cut down forests for timber. In the 1890's, the Hill brothers established a nearby resort and offered tours to the ruin for their guests. Of course it was quite acceptable back then to take a souvenir or two. Several mummified bodies had been found, though most were lost to looters and private collectors. Finally the area was protected in 1907 when it became declared a national monument.

More than 40 sites are protected with in the monument's 533 acres. They range from pit houses dating back to 550, to cliff dwellings from the 1280's, to surface pueblos built in 1400.

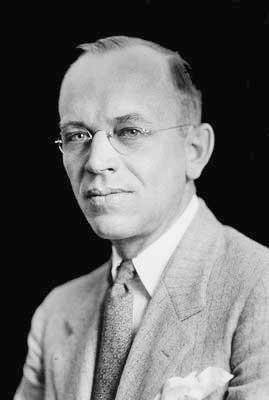

In 1924, ecologist Aldo Leopold persuaded the US Forest Service to establish the Gila Wilderness, the nation's first designated wilderness area.

Here are the different levels of land protection:

National park: A protected area that requires the approval of Congress to be created.

National monument: The president can declare an area to be a national monument without the approval of Congress. This may happen if he feels Congress is moving too slowly and the area would be ruined by the time they made it a national park. Monuments receive less funding, have fewer protections for wildlife, and usually have less diversity than a national park.

Wilderness: This protects federally managed lands that are in pristine condition. Human activities are restricted to non-motorized recreation (such as backpacking, hunting, fishing, horseback riding, etc.), scientific research, and other non-invasive activities.

National forest: National forests are mostly forest and woodland areas owned by the federal government. Unlike national parks, commercial use is permitted, such as timber harvesting, livestock grazing and recreation.

Aldo Leopold (1887 - 1948)

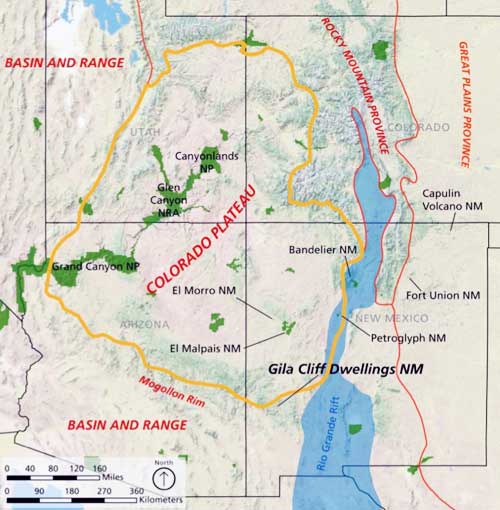

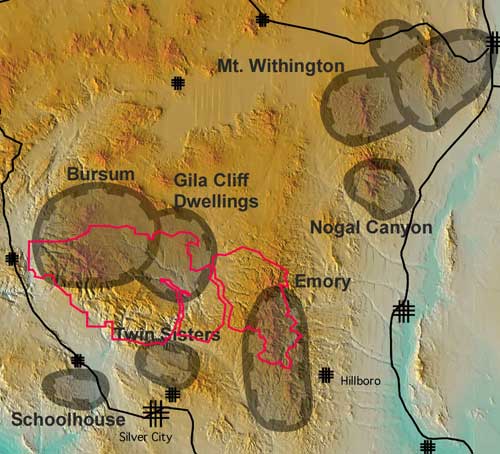

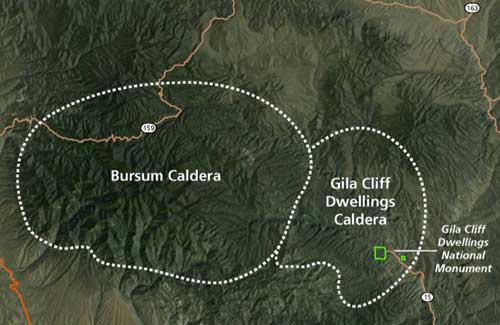

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is part of the Mogollon–Datil volcanic field, which lies on the southeastern margin of Colorado Plateau. Between 35 and 28 million years ago, this area experience the eruptions of several supervolcanos (the largest volcanic eruptions known to occur on earth). They produced catastrophic eruptions that were 1,000 times more powerful than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. The end result was a cluster of calderas... including the one we were in now.

A cluster of calderas

Once the calderas collapsed, they filled in with younger lava flows, making the features difficult to see in the landscape today. The Mogollon Mountains were named after Don Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón, Spanish Governor of New Spain (including what is now New Mexico) from 1712 to 1715.

The Bursum Caldera is 25 miles across.

This is a cross section from the left end of the Bursum Caldera to the right end of the Gila Cliff Dwellings Caldera. Click for a larger view

Different groups of people have inhabited this region for the past 3,000 years because the river offered a reliable water supply. But we have no hard answers as to who built the dwellings in these cliffs or why. We do know that they only stayed a few decades though. We also know they belonged to a larger group known as the Mogollon (mo-go-yon).

The Mogollon culture has been accepted as distinct from the ancestral Puebloans farther north. A large subset of the Mogollon culture is the Mimbres branch, centered in the Mimbres Valley not too far from here. And yet, this small group of people was different. It is suggested they came from the Tularosa River region (about 60 miles to the north). Unlike the traditional groups of the area who built pueblos on the mesa tops, they built pueblos inside the cliffs using rock, mortar and timber. They lived here between 1276 and 1287.

There were many regional variants of the Mogollon culture... the Mimbres, Jornada, Forestdale, Reserve, Point of Pines, San Simon, and Upper Gila branches. The entire Mogollon occupation spans around 1,000 years.

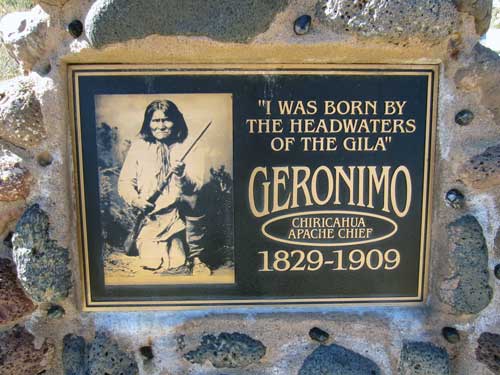

In the 1500's, the Apache migrated to this area. Geronimo was born near here when battles raged with Mexico. 30 years later, the US moved in, built army posts, and by 1870 began to relocate the Apache to reservations. in 1886, the last of Geronimo's people (the Be-don-ko-he) were removed from these lands.

Apache leader Goyahkla (or Geronimo)

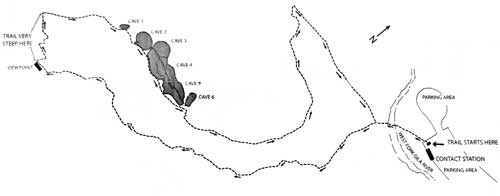

We were to meet the ranger at the caves. This required a brisk walk along a one-mile loop trail... with a fairly steep climb at the end.

The Cliff Dweller Canyon trail. Click for a larger view

The West Fork of the Gila River

There were several bridges that ran back and forth over a small stream. There wasn't much water in it at the moment, but a small spring ensures a constant flow that helps sustain the canyon.

Our first glimpse of the caves overhead

At the top

There was already a small group gathered for the tour. Crystal was our guide. She told us a bit about the dwellings and the people who lived here.

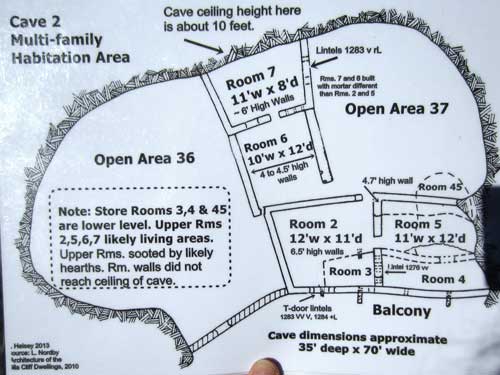

Again, there were no definite answers. It is believed they were a Mogollon tribe based on their style of pottery. There are about 40 uniquely shaped and sized structures built inside of five natural caves. With only 40 to 60 people, it wasn't very crowded. Evidence shows they traded both materials and ideas (such as building styles). They grew corn, beans and squash but also hunted and foraged. They lived here for 30 or 40 years then just left. There are records of a 20-year severe drought in the region. Perhaps that forced them out to here away from rest of their tribe. When the drought was over, they could return home.

There were these mysterious holes in the ground nearby. Geologists originally argued they were natural, but this type of rock wouldn't weather like this naturally. Therefore they are man-made. But for what purpose? It could be for grinding corn, but it has also been suggested they are gate post holes... not so much for actual protection but more symbolic.

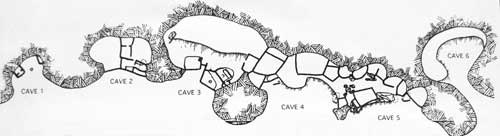

A map of the caves. Click for a larger view

We then entered Cave 1. Of all the caves, this is the least preserved. All the timbers are gone and there were only a few walls and other structural features. There were not many artifacts found, just a few pottery shards. There were black marks on the ceiling from fires. And there were a few red lines of pictographs.

But even from these scant clues, we gain some insight into these people. For example, the pottery style was from some 70 miles away although the items were made from local clay. The pictographs tell us that had had enough free time for leisure activities. The short walls indicate that there were three small storage areas and a larger central room. This was probably the home of one family of perhaps 4 to 8 people. The black soot on the ceiling and the circle depressions on the floor suggest they cooked in large, round-bottom pots.

Cave 1

A storage area and soot marks on the ceiling

Pot holders for cooking

Hints of pictographs

Archaeologists classify ceramics based on how the pots were made and the materials used for the paste, slips and pains.

Cave 2 is the oldest, built in 1276. In the 1880's, it was still in good shape. But when Bandelier wrote his first report in 1898, it revealed that vandals and relic-seekers had broken down walls, burned roofs and removed pots, tools and other items. Back in those days, people made a living any way they could off the land. And since it was not owned, it was ok to take things. Actually, the land was owned (in a sense). It had been promised to the Apache. But the US government reneged on the deal. So the Apache started killing people in an attempt to drive them away. In retaliation, people burned down these places so the Apache couldn't use them as hideouts.

Walking to Cave 2

The sturcture now...

... and before it was burned and damaged.

We can only guess that the smallest rooms were for storage; the medium ones for residences, and the larger ones for communal gatherings.

A photo of the inside. The walls are all original.