CAPITOL & PROMONTORY (Day 2 - part 4)

We headed north out of Salt Lake City.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on Capitol Street

Marathon Petroleum's refinery ... and rock quarrying

Interstate 15 north

Part of the Wasatch Mountain range

Cutting over on State Route 83

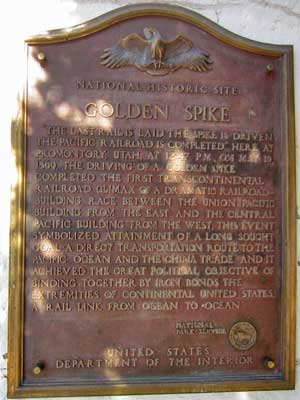

We arrived at Golden Spike National Historic Site at Promontory Summit, north of the Great Salt Lake. This is where the first Transcontinental Railroad was completed... where the Central Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad met on May 10, 1869. The rails were jointed by a ceremonial Golden Spike. The area became preserved as a national historic site in 1965.

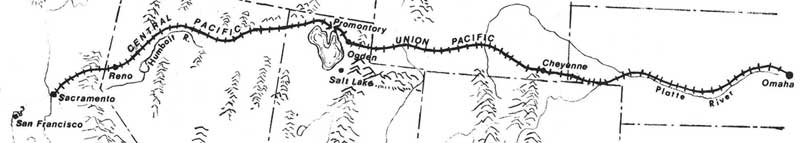

The route of the Transcontinental Railroad (click for a larger view)

The project took six years (and six million spikes) to complete. The continuous railroad line ran 1,912 miles. The Western Pacific Railroad Company built 132 miles from Oakland to Sacramento; the Central Pacific Railroad Company constructed 690 miles from Sacramento to here; and the Union Pacific built 1,085 miles from the end of the eastern rail system at Council Bluffs (Iowa) to here.

Surveyors worked hundreds of miles ahead. Graders worked some 20 miles ahead of the tracklaying gangs. They cut ledges, blasted hills and filled in ravines using picks, shovels, one-horse scrapers and black powder.

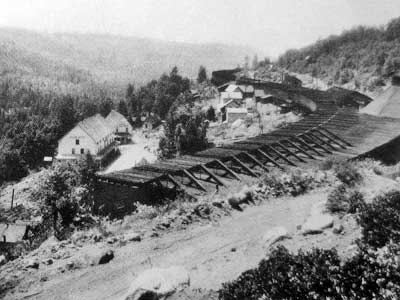

(left) Blasted tunnels .... (right) In order to get through the Sierra Nevada mountains, some 37 miles of snow sheds and sloped galleries were needed to handle snow drifts and avalanches.

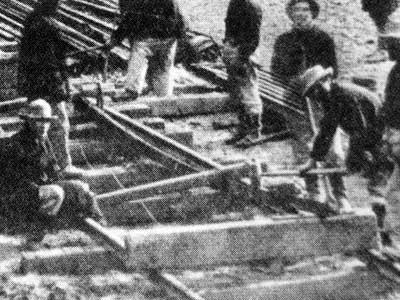

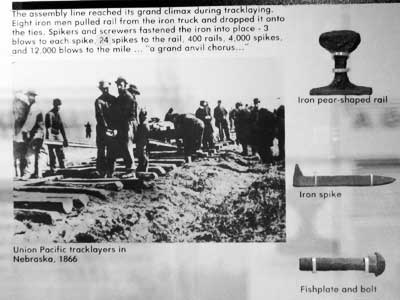

Eight men would pull a 30-foot, 560-pound iron rail from a truck and drop it onto the ties. Spikers and screwers fastened it into place... 3 blows per spike, 24 spikes per rail... and 2,500 ties, 400 rails, 4,000 spikes, and 12,000 blows per miles. A gang could lay two pairs of rails per minute.

The Central Pacific built sawmills in the thick forests of the Sierra Nevada mountains and produced perfectly identical ties. The Union Pacific used hand-hewn ties delivered from tie-cutting camps

The Central Pacific hired some 10,000 Chinese workers, since most other folks were off trying to strike it rich with the gold craze. The Union Pacific hired immigrants, ex-slaves and Civil War veterans.

Finished!

During the final ceremony, speeches were given as was a long prayer. Then Governor Stanford (president of the Central Pacific Railroad) picked up a hammer to drive in the final spike... but missed! Then Dr. Durant (vice president of Union Pacific Railroad) took his turn... and missed! Of course, all the workmen laughed and applauded. Then the two crew bosses, James Strobridge and Samuel Reed, grabbed a pair of hammers and proceeded to drive the spike in.

I'm standing on the exact spot where the tracks were joined.

Replicas of the Central Pacific Jupiter and the Union Pacific No. 119

A peak inside the steam trains

Outside stood the restored Southern Pacific monument.

In 1916, this monument was placed near the historic golden spike site. By 1965, the aging monument had been damaged by weather and vandalism. Early restoration attempts failed because water often remained trapped inside. In 2001, it was removed from the ground, allowed to dry out, and moved here. The old stucco was replaced with modern, breathable masonry.

The monument in 1927

The visitor center

Tools of the trade

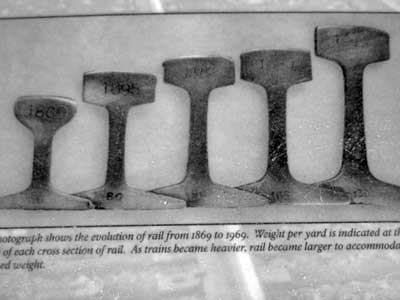

The evolution of the rail from 1869 to 1969. As trains became heavier, rails became larger. Before the Civil War, rails were made from iron. After the war, steel production drastically increased and costs dropped. Shiny new steel rails required less material and increased efficiency. Over time, all pear-shaped iron rails were replaced with T-shaped steel ones.

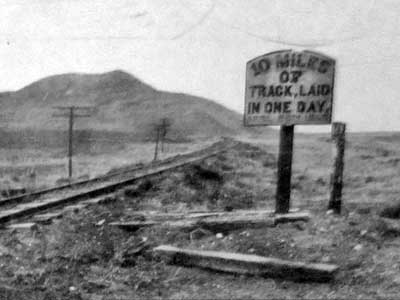

In the final days, with the lines only 25 miles from each other, a friendly wager was made between the two railroads... who could lay the most track in a day? Union Pacific laid an impressive 7 miles... but Central Pacific pulled off 10 miles! This sign was put up for passengers to see from the train.

A model of the ceremony

For the ceremony, four gold and silver spikes were set into predrilled holes of polished laurelwood. These were promptly removed and replaced with iron spikes into a tie of white pine. The original spikes were engraved later.

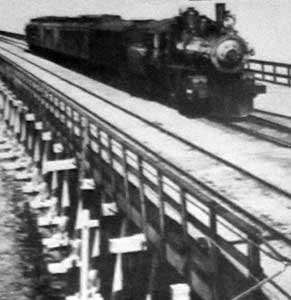

The Lucin cutoff

Unfortunately Promontory Summit's sharp grades and many curves became a problem as trains became heavier and longer. The trains had to be broken into segments and attached to helper locomotives. This resulted in "traffic jams" even in good weather. Since the Great Salt Lake had also been receding, a plan was made in 1902 to build a track straight across the lake from Ogden to Lucin. Because of the lake's soft bottom, a 12 mile trestle was built, using over 38,000 pilings (with several being driven down 120 feet before they hit solid ground). The new route saved 44 miles; trains no longer had to be broken down; and travel time was reduced from 36 to less than 10 hours.

The Promontory line remained, but only one or two trains came through per week. In 1942, steel was needed for WWII, so a small "undriving" ceremony was held, and within a few months, the line was salvaged.

The old trestle ... and new causeway

Unfortunately again, after 50 years of use and even heavier trains, the Lucin cutoff trestle started failing. So it was decided to build a permanent causeway. Nearby mountains were blasted apart, and over 45 million cubic yards of rock were used to fill the 25-foot deep lake. The causeway is 600 feet wide at its base and only 35 feet wide at the top. It was completed in 1959. The old trestle was finally pulled down in 1993.

We were then torn about what to do... we only had enough time to either 1) watch the steam trains actually run down the track or 2) explore a nearby site my friend Rebecca had told us about, the Spiral Jetty. We chose the jetty.

It was only about a 16 mile drive south, but the rough road left a bit to be desired.

Views of the Great Salt Lake

Driving along the shore but uh... where did the water go?

Trying to befriend the unfriendable

return • continue