ZION & BRYCE (Day 14 - part 2)

Inside the Human History Museum

An overview of the canyon, carved by the Virgin River

The earliest people to explore the canyon were the hunter-gatherer Archaic people dating back 2,500 to 7,000 years ago. They were eventually replaced by the Ancestral Puebloan cultures around 100 BC. They disappeared around the year 1200, after which the Southern Paiute established themselves here. They called the canyon 'Mukuntuweap,' meaning 'straight-up land.'

A Southern Paiute hunter, 1873. The Paiutes moved with the seasons.

Many of the early Spanish explores as well as American trappers passed either a bit too north or too south to have actually discovered the canyon.

Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez, Jedediah Smith, William Wolfskill, Captain John C. Fremont

Mormon leader Brigham Young led his followers to Utah in 1847 with the goals of escaping religious persecution and growing cotton. In 1858, he sent Nephi Johnson to scout the river. It was his recommendations that led families to settle in the valley.

The first were Isaac and Elmina Behunin in 1863, who had come from New York. Feeling the place was a sanctuary with the cliffs serving as temples, Isaac named it Zion, a Biblical reference to a "place of refuge." The Crawfords arrived in 1879.

The Mormons make their way to a new home.

The settlers relied on the water from the North Fork of the Virgin River which flowed through the canyon. Although it flowed year-round, its levels weren't very consistent... being too muddy to drink during the spring floods or becoming too shallow in the summer, with side tributaries turning into dry washes.

Tourism began in the early 1900's as roads and trains allowed for easier access.

The number of visitors went from 3,692 in 1920 to 21,964 just 6 years later. Today the park receives over 3.6 million visitors.

Promotion came in the form of Harper's Magazine (1876 issue)...

... and an article by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh (a mapmaker and painter) in Scribner's Magazine, 1904. This helped lead to the creation of the park.

Zion became a national monument in 1909 and a national park 10 years later. The building of structures in the canyon was aided by the Cable Mountain Draw Works, a pulley system designed by David Flanigan to lower lumber down from the rim, thus saving days (even weeks) of hauling over rough roads. Starting in 1906, the system ran for some 20 years.

David's father told him of a prophesy that Brigham Young made back in 1870 that "someday lumber would come off those canyon walls, flying like a hawk." When David visited the canyon in 1888 at 15 years of age, he was already dreaming of ways to make the prophesy come true.

The top of the Cable Mountain Draw Works

The informative movie

We then turned onto the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway that would eventually lead us out the east side of the park.

To read about my previous visit to Zion (including hiking the Narrows) in 2014, visit my

California Trip

|

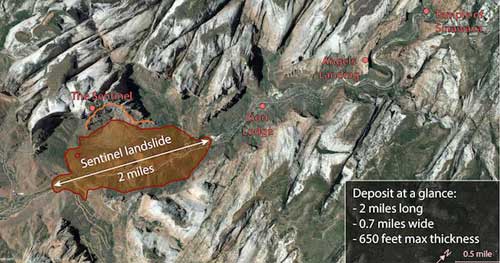

The Sentinel (7,157 feet) towers over the valley to the far left.

The Sentinel is actually largely responsible for how the canyon looks today. Around 4,800 years ago, a large part of the peak collapsed in a giant landslide which blocked off the valley, essentially creating a dam which formed a 2.5 mile long, 400 foot deep lake in the canyon that lasted for about 700 years. Eventually it was filled with sediment, which is why the valley floor is actually flat instead of in a sharp v-shape. The Virgin River continues to carve down into it today.

While rock slides happen all the time, it's unclear what caused this one. There's no real evidence of an earthquake but perhaps it was due to some weaker shale layers within the rock. The whole thing took place in about 20 seconds, with rocks rushing down the peak with speeds of up to 200 miles per hour, crushing and burying everything instantly. The volume was 90 times the amount of concrete used in the Hoover Dam. It took about 5 - 10 years for the lake to fill.

Crossing over the Virgin River

The Beehives (named for their shape) on the left and the Sentinel on the right. I wonder if they were part of the giant mountain landslide?

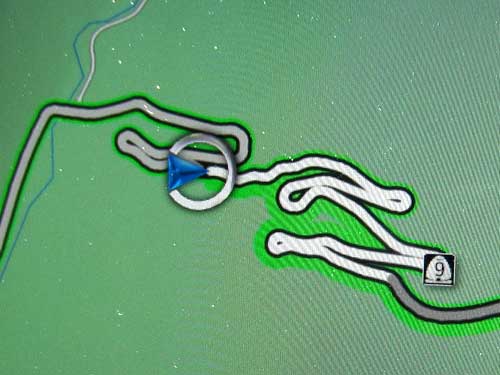

The road gets curvy going up, up, up!

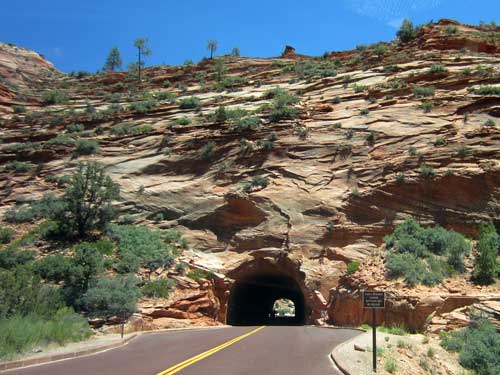

In the 1920's, this arm of the canyon was a dead end. A road over the tall cliffs was impossible... but a tunnel through it wasn't!

The Great Arch overlooks Pine Creek Canyon.

This large hole in the cliff...

... is one of several windows (or galleries) that line the tunnel since there are no artificial lights inside.

Looking down where we had just been

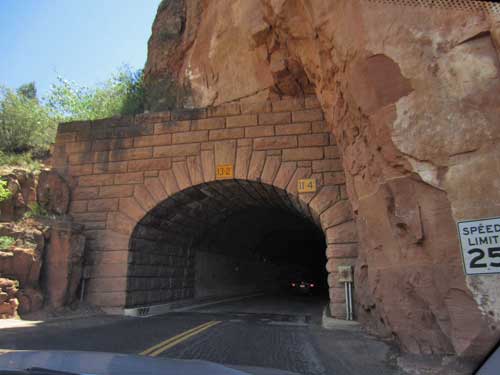

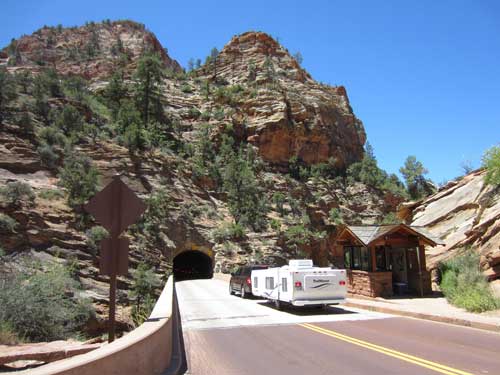

Today, tour busses and RV's are too large for two way traffic, so we had to wait to take turns.

Entering the tunnel

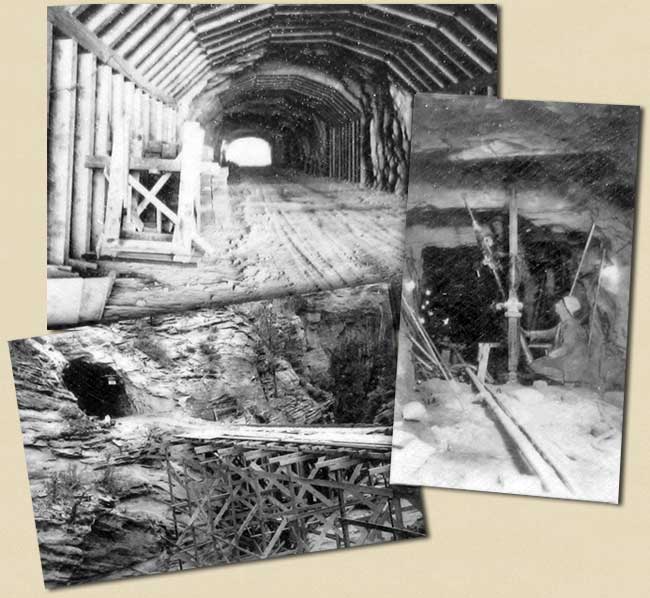

The Zion-Mt. Carmel tunnel took 3 years to build. Completed in 1930, it was the longest in the country at 1.1 miles. Six large galleries in the sandstone walls allowed for light and (very brief) views.

In the old days, people were able to stop and take in the scenery. But a continual stream of cars keeps us flowing nowadays.

Don't blink!

There was a small parking lot on the other side of the tunnel where we stopped and appreciated the construction marvel.

Wow! That's a tight fit!

We emerged into a very different landscape... one filled with colorful mesas and slickrock.

Slickrock sandstone was formed when rounded beach sands were cemented together to create a uniform layer. The texture is actually somewhat rough, like sandpaper. The name was given by the early settlers because their horses' metal shoes had difficulty gaining traction on the rock's sloping surfaces. It does, however, become quite slippery when wet.

return • continue