We made our way back into the sound, learning even more fascinating geological history. The sides of the mountains were carved into 'steps' with each one representing the bottom of the u-shaped floor of another glacier. The bottom one (the last one above the water, that is) was from 600,000 years ago. The last ice age here was around 20,000 years ago.

Turning back into the sound

Looking all the way back toward the end. Again, use the boat for scale.

Palisade Falls (left) and Disappearing Falls (right, so named because the wind often blows it away before it can reach the ground). Note the 'step' in the land which represents the previous floor of the glacier.

Palisade Falls

Palisade Falls

It began to get rather chilly and the rain started to lightly fall. We approached Copper Point again, and there were seals on the other side as well. It was unbelievable how an animal with just flippers could climb to the tops of these rocks! One was playing at the bottom of the rock... jumping into the water, then out onto the rock, then back in, then out.

Sometimes they slept in the oddest poses!

Fresh and sleek from the water, climbing up the steep rock

One strong jump and voila, back on land

A seagull watches from nearby, clearly unamused.

Sterling Falls was where the adventure part of the journey was to take place. Those who wanted to, could put on bright orange, thick waterproof jackets and stand in the blasting spray as the boat pushed its nose up to the falls. At some point, we had to hide the cameras!

Sterling Falls is three times the height of Niagara Falls. It is glacier fed, rather than being solely dependent on rain water. Unfortunately, at the rate at which the glacier is disappearing, the falls will be gone by 2020.

Approaching the falls

The way the fine spray rippled outward was mesmerizing.

Leaving the falls behind us

The large horizontal stripes in the rock are more evidence of glaciers. Use the kayakers for size.

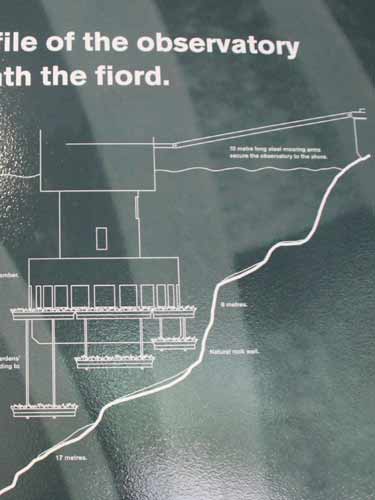

The final highlight was Milford Discovery Center and floating underwater observatory, built in 1995 in Harrison Cove. The location was chosen because it was sheltered from wind, had minimal risk of tree avalanche, had a good cross-section of marine life, and had a slope below water level (to allow the observatory to stay close to land as it rose and fell with the tide).

We first got a bit of history about the observatory, then headed down the stairs to the observation platform some 30 feet (10 meters) below the surface.

The Discovery Center (left) and floating observatory (right)

The observatory is surrounded by trays containing underwater 'gardens.' These can be raised or lowered depending on water conditions (such as storms or saline levels).

Demonstrating the thickness of the glass. To the left is a model of the station.

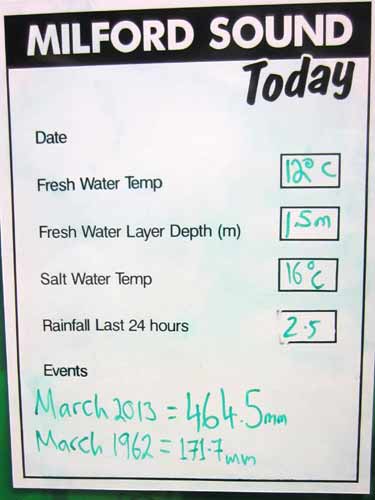

Today's stats

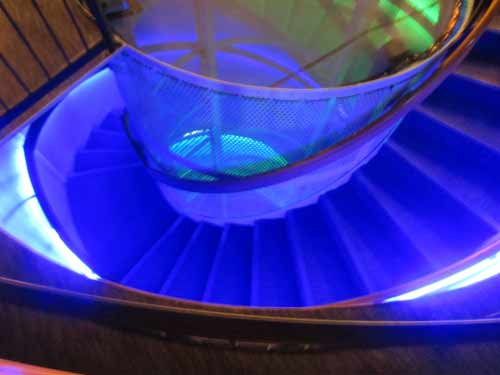

Descending the spiral staircase to a different world!

Heavy rainfall soaks through the forest floor, becoming stained brown by leaf litter on its journey to the fiord. This tea-colored band of fresh water is up to 30 feet thick and floats on top of the heavier salt water. This filters out the light, creating unusually dark conditions in the calm and relatively warm sea water beneath. Black sea corals (and other sponges and animals) which are normally found at depths of several hundred feet, thrive here less than a few dozen feet below the surface. Anything below 130 feet and the water is too dark for most life.

Black Coral... the star of the show!

So why isn't Black Coral black?? Well.... the skeleton is. When alive, this structure is completely covered by white polyps (tiny sea anemone-like animals). Using stinging tentacles, these stationary creatures fish for microscopic animals that float into rage. The black skeleton grows just like a tree, with growth bands that record environmental occurrences (such as good or bad growing conditions).

More black coral

The animals were free to come and go as they wish.

A sea pen (left) and a sea anemone

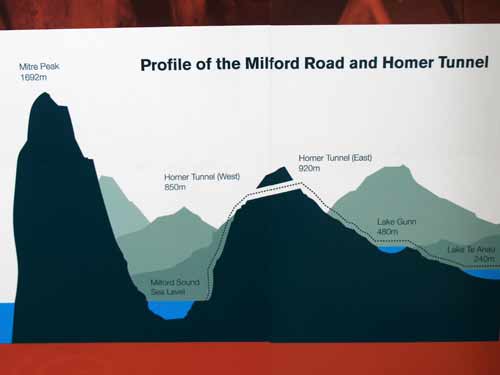

We then went back upstairs to have a look at the discovery center. It contained lots of information about the fiords and surrounding area... including the building of the Homer Tunnel.

See, I told you it was a steep descent through the tunnel!

Some of the construction workers. The tunnel is named after a gold-panner named William (Harry) Homer, who discovered the area in 1889.

We went out on the dock and waited for the next passing boat to take us back. The afternoon light and clouds played on Mt. Pembroke. A few minutes later, we were disembarking and making our way back to the car.

Nearing the dock with its nearby giant waterfall

A farewell view

"Confined space hazard"? Did they have these signs on WWII submarines?

return • continue