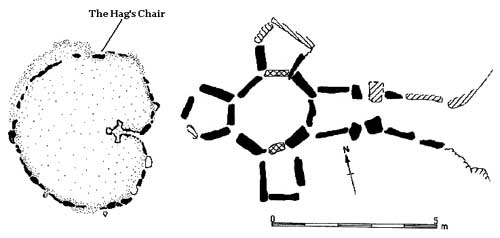

Perched on the highest hilltops in County Meath, the Loughcrew cairns were built by Neolithic (New Stone Age) societies, Ireland's first farmers. These communities built large communal tombs (megaliths) for their dead. There are four main types of tombs: court tombs, portal tombs, passage tombs and wedge tombs. The typical passage tomb is shaped like a cross, with a long central passage leading to a main chamber, off of which there are three smaller chambers. The dead were cremated and the remains placed in the chambers above the ground. The tombs were then covered in great mounds of earth and stones called cairns. This means they were built from the ground up and not dug inside an already existing hill.

Loughcrew (from Loch Craobh or Lake of the Branches) is also called Sliabh na Caillighe (Hill of the Witch or Mountain of the Hag, depending on how nice you want to sound). Built around 3,000 BC, the cairns form the largest complex of passage graves in Ireland, with a concentration of around 30 passage tombs (although there were probably once as many as 50).

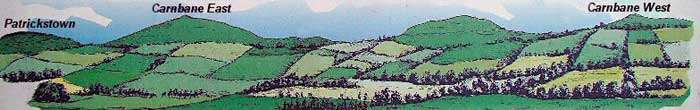

The prehistoric cemetery is spread across three adjoining hilltops: Carnbane East, Carnbane West and Patrickstown. Only the east one was open. The west one is located on land owned by a farmer who does not allow public access to the site.

Signs were both in English...

... and Gaelic

Location of various sites

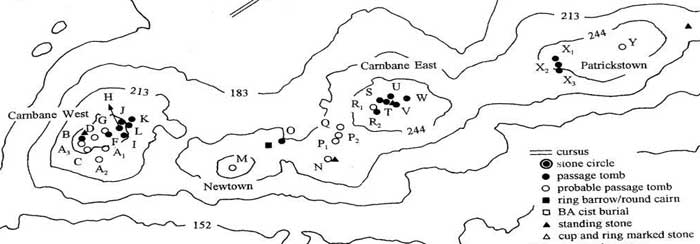

The one we would be visiting

It was an incredibly scenic walk up a long, sloping grassy hill.

Regan battles with the gate.

Heading up

Exquisite views!

Just a rock or an indication of things to come?

Sheep dotted the landscape...

... although some tried to be more discrete about it.

Cairn S and Cairn T

Getting closer

Cairn S still has a passage, chamber and kerbstones (or curbstones, the outside ring of stones) but the cairn stones that once formed the top mound are gone. It wouldn't be at all surprising if most of them had walked off to build the zillions of field walls criss-crossing the countryside (if you examine some of the above pictures, you can see them).

The kerbstones of Cairn S

The inner passage and chamber

Making our way around the giant central Cairn T, we arrived at Cairn U. Again the mound was missing but the inner passage was much more obvious.

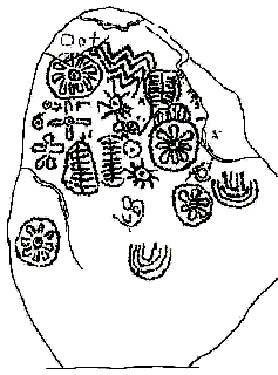

A distinguishing feature of Irish passage tombs is the presence of rock art, with circles, spirals, arcs, triangles, zigzags and flowers being common.

We then approached Cairn T, the highest point of the whole complex. It was open and a guide sat outside. He shared some stories and information, then gave us a flashlight to go inside.

In 1980, researcher Martin Brennan discovered that Cairn T was positioned to receive the beams of the rising sun on the vernal (March) and autumnal (September) equinoxes. The light shines down the passage and illuminates the carvings on the backstone. The event lasts for 50 minutes. The orientation of numerous Irish sites based on solar and lunar cycles reveal the importance of astronomy to the builders.

The cairns were used through the Bronze Age, but then very suddenly, the people changed from doing cremations to burials. Perhaps a new group of people with different traditions took over.

Mesolithic (8000 - 4000 BC) - hunter-gatherers

Neolithic (4000 - 2500 BC) - farmers & cairn builders

Copper and Bronze Ages (2500 - 500 BC)

Iron Age (500 BC - AD 400)

38 kerbstones contain the stone mound that is approximately 120 feet in diameter. It originally was also covered in a layer of white quartz, causing it to be called Carn Ban or the White Cairn.

Cairn T is one of the oldest free-standing buildings in the world. Loughcrew is estimated to be 5,200 years old.

The location and layout of the inner passage. Note the cross shape, with a large central chamber and side chambers.

Heading in. One could only go a short way along the passage.

Most of the carvings are presumed to be original since they are inside tomb.

The backstone is carved with many symbols.

It is also called the Equinox Stone.

A hole in the corbelled roof allowed for light. Originally this would have been covered over with a capstone.

After returning to the outside world, we made the climb to the top.

The top of Cairn T, looking in the direction of the entrance

This is where the capstone was.

On top of the world!

Looking down on Cairn S

And an overview of Cairn U on the other side. Originally 6 cairns encircled Cairn T, but only 3 of them somewhat survive.

At the north side of Cairn T was a large stone called the Hags Chair. Technically it is a kerbstone but is substantially bigger than the rest. Perhaps it was used to sit and watch the stars.

A cross carved on the seat dates to the 17th century when priests were hunted and masses were held in the open air.

Local tradition says that a wish you make while sitting on it will come true. Only Regan will know!

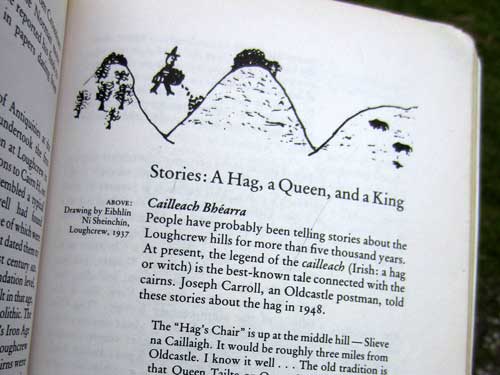

The guide let us read a story about the hag in one of his books.

In order to rule over all of Ireland, the hag (Cailleach Bhe'arra) had to complete a feat of enormous strength. She had to leap from hill to hill her apron full of stones. As she jumped from peak to peak, she dropped a handful of stones, which became the cairns. On her final jump, she fell and broke her neck. She was buried under the stones on the side of the hill.

We passed one final cairn, Cairn V, then began the walk back down.

Although there is not a lot left of Cairn V, it is believed that it indicated the winter solstice sunrise.

The path down