BAYOU & PLANTATION (Day 6 - part 4)

Oak Alley Plantation is located on the west bank of the Mississippi River in the community of Vacherie, St. James Parish. It is named after its 800-foot-long canopied entryway created by a double row of 28 southern live oak trees which are 200 - 300 years old. The trees can live up to 500 years old.

Click the image for a larger view

We had tickets for a 1:45 tour of the big house, so we quickly headed over.

In spite of how lovely this looks, this path is not the actual oak alley. That's on the other side of the house.

There are 28 Doric columns wrapping around all four sides of the house that correspond to the 28 oak trees in the alley.

The roof is made of slate and originally had four dormers. ... More of the columns

This is the amazing pathway ... looking towards the levee...

... and back towards the house.

Unfortunately we weren't allowed to take any photos inside.

Originally known as Bon Séjour, the sugarcane plantation was established in 1830 by Valcour Aime. In 1836, he exchanged this property for the planation that his wife's brother, Jacques Roman, owned. The following year, Roman had his slaves begin building the mansion. The brick walls are 16 inches thick (which provided insulation and storm protection), finished with stucco and painted white to resemble marble.

Jacque and his wife Celina owned 220 slaves. Sugarcane, known as white gold, was a very high-risk but also high-reward industry. But with 12 siblings (all in very powerful positions) the family already had lots of land and wealth. Jacque and Celina Roman had 6 children of which only two daughters and one son made it to adulthood. Jacque had never been very healthy, but as he got older and sicker, the household became unstable. He feared his brothers would take over. Jacques died at the age of 48 of tuberculosis and Celina had to take over managing things. Unfortunately she was just a socialite and had never been taught any of the skills of running a sugar plantation. She fixed up the sugar mill and hired new workers. Many of these people, however, took advantage of her inexperience and greatly overcharged her. During the next 10 years, the estate was nearly bankrupted. To pay off some of the massive debt, she was forced to sell slaves, furniture and silverware. In 1859 she handed control over to Henri, her 19-year-old son.

Jacques Télesphore Roman (1800 - 1848) ... and his son Henri (1839 - 1905)

Marie Therese Josephine Celina Pilie Roman (1816 -1866)

In 1861 (during the Civil War), the price of sugar dropped. Then the slaves were freed in 1866. The estate was sold at a public auction at a loss. The land passed through many hands since the next several sets of owners could not afford the cost of upkeep. By the 1920s the buildings had fallen into disrepair. In 1925 Andrew and Josephine Stewart acquired it and renovated the house. They turned it into a cattle ranch. Andrew died in 1946, and when Josephine died in 1972 (at the age of 93), she left the estate to her nonprofit foundation, which opened them to the public.

Andrew and Josephine Stewart

We saw the living room with a wooden fireplace that had been painted to look like marble. It ironically cost more to hire the artists than to import actual stone.

The dining room could seat 12. The sugar bowl on the table was SUPER tiny. They didn't use sugar like we do now! Known as domestiques, the slaves in the house spoke French and worked closely with the family. They held a variety of jobs, including as servers. They therefore could discretely listen in on family discussions and pass along any important information to the field workers regarding upcoming changes.

Jacque had rheumatoid arthritis and gout which often restricted him to the master bedroom. At night he slept in a bed stuffed with Spanish moss, and during the day he rested in a bed with horsehair. A portable table allowed him to still work.

We were allowed to take photos on the upper outside balcony.

A large ship happened to be passing by on the river! Given the angle with the levee, it looked like it was floating by on the grass.

A 100- year-old magnolia tree

The different gardens

After the tour, we headed through one of the gardens to the old car garage which now houses the Sugarcane Theater.

Views of the mansion

(right) Skimmers were used to remove the foam from the juice as part of the boiling process.

Hogshead-sized barrels held 62-140 gallons of sugar and weighed 700-1,200 pounds. ... Cane juice was boiled in cast iron kettles of different sizes.

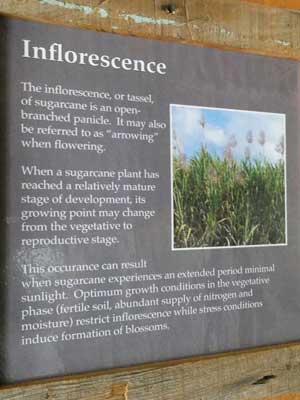

The tassel (or inflorescence) of sugarcane is made up of thousands of tiny flowers that produce seeds.

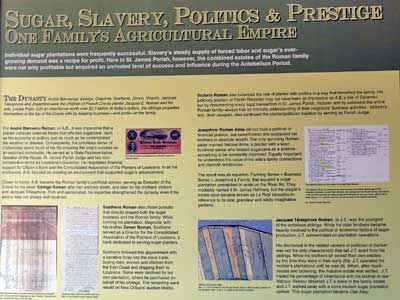

All of the Romans were successful. ... The face of Andre Beinvenu Roman (one of Jacque's older brothers) graces the front of a bank bill.

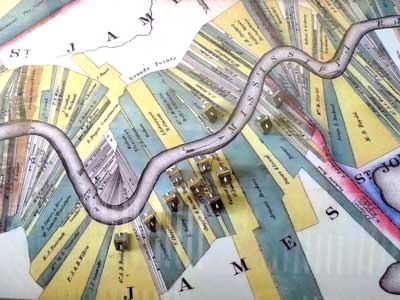

They owned many plots of land along the river.

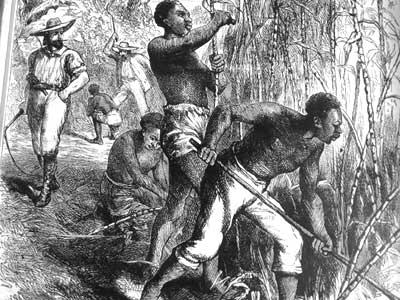

Sugarcane was a labor-intensive crop and the driving force behind the high demand for slaves. Most crops, such as corn, are planted every year, but sugarcane, once planted, grows and is harvested each year for the next 3 to 4 years. As a result, sugarcane fields vary dramatically in height, with one field being recently planted while another may be mature.

The 1850s:

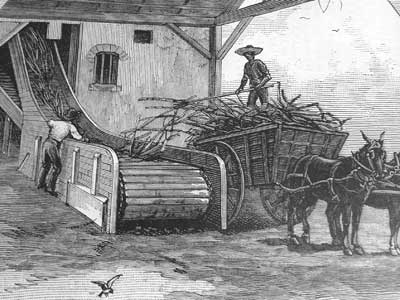

Small plantations were rarely lucrative. The crop was so time consuming that planters only got significant profits with large production volumes. At Oak Alley, 600 acres of sugarcane were grown and up to 80 field slaves were tasked with planting, tending, weeding and harvesting. Everything was done by hand. Wood also needed to be cut for the sugar mill or repairing roads. A bad road that was mucky or unstable could cause the entire operation to stop for days. Oak Alley used mule-driver railroads to solve this problem, regardless of weather. Harvest season was between October and January. The crop couldn't be allowed to freeze or it would be worthless. The cane was cut, brought to the sugarhouse and squeezed for its juice which was crystallized into sugar by boiling. It was a 24 hour operation that went on for weeks, with slaves working 18-hour shifts.

Today:

While the plant has not changed much and still grows for several years before having to be replanted, modern machinery and techniques have greatly improved things. In 1850 if a planter could expect 1,500 pounds of sugar from an acre, that number is closer to 8,000 pounds today. Crop rotation, fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and fungicides ensure a successful crop. The use of ripening agents and meteorological predictions lead to a more predictable harvest season. A single machine separates the leaves from the stalk, cuts the stalk into billets and shoots them into a wagon, leaving enough stubble to sprout next year's crop. The wagons unload into trucks which deliver it to a mill for processing. Even planting is done by machine.

We spent about 15 minutes watching a video on the modern process. Here are some of the steps:

return • continue