We got a bit lost getting to Saguaro National Park, but eventually we found it.

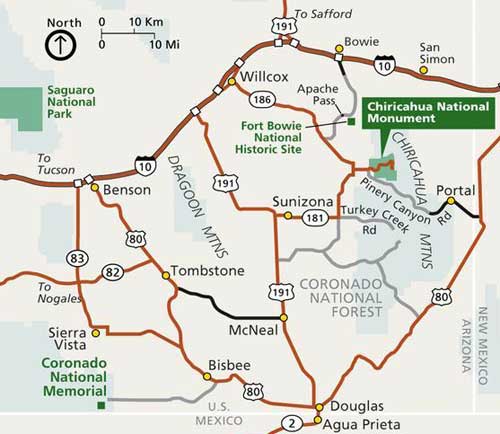

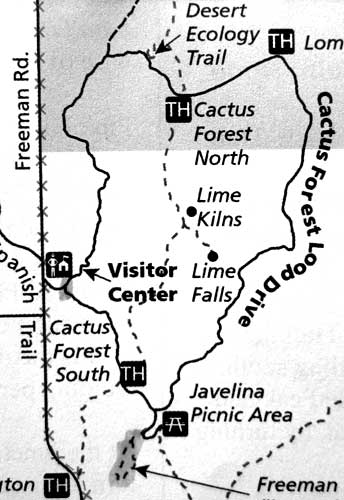

A map of the area and some of the places we'd already seen

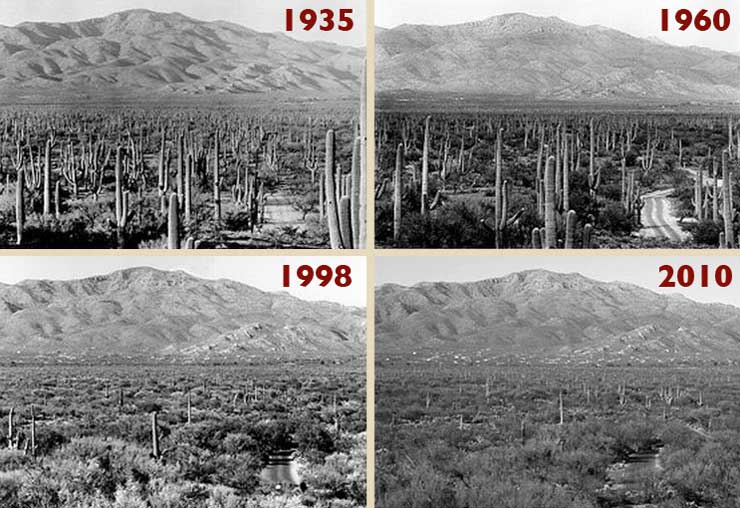

Saguaro National Park was first established as a monument in 1933 on the east side of Tucson (known as the Rincon Mountain District). In the 1960's, however, researchers noticed a decline in the number of cacti and felt more of this landscape needed to be protected. And so, the Tucson Mountain District on the west side of the city was also created. Both sections became elevated to National Park status in 1994.

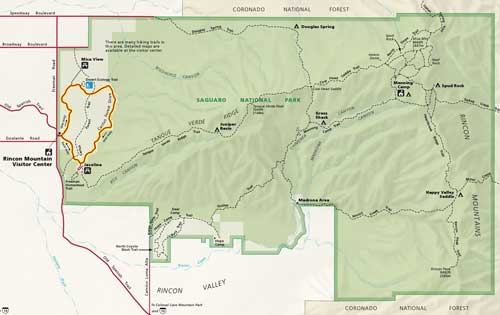

We visited the east side. This side has fewer saguaros than the west side, but they are larger due to higher amounts of rainfall and runoff from the Rincon Mountains.

The two districts lie about 30 miles apart. Together they preserve over 91,000 acres of Sonoran desert.

An early park entrance sign. Note the alternate spelling of Saguaro. In either case, the pronunciation is the same: suh-wahr-oh. It is believed to be an Opata word (who lived in northern Mexico).

Click for a larger view

We first stopped in the visitor center to learn more about these prickly giants.

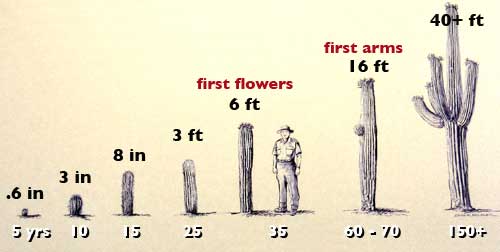

The saguaro is a large tree-like cactus native to this area. Saguaros grow only from seed, never from cuttings. One plant produces tens of thousands of tiny, tiny seeds in a year (about 2,000 seeds per fruit) and as many as 40 million in its lifetime. Out of these millions, however, only a few survive to adulthood. They grow VERY slowly. After one year, a seedling may only be 1/4 inch tall, and after 15 years, it's barely a foot tall. But those that make it to 150 years and older can tower at 50 feet and weigh over 16,000 pounds.

The saguaro in the park are near the northernmost limit of their natural survival zone.

The life of a saguaro. The growth rate is strongly dependent on precipitation.

Typically this area receives less than 12 inches of rain per year. It can go for months without a single drop. Both plants and animals have had to adapt to this.

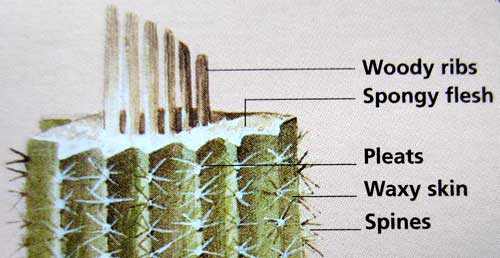

Many features help the saguaro store and conserve water. Accordion-like pleats allow it to visibly expand. Its spongy flesh acts as a reservoir, storing the water as a slow-to-evaporate gelatin-like substance. The cactus has no leaves which could lose water. All photosynthesis is carried out by the trunk and branches. Spines give it shade and shield it from drying winds, not to mention discourage animals for eating it. A waxy skin reduces moisture loss. Its roots are not very deep (only about 3 inches down) but stretch out as far as the saguaro is tall. In a single rainfall, they can soak up as much as 200 gallons of water, enough to last the cactus for a year.

Most animals survive this area by avoiding venturing out in the heat of the day. Those that do have special adaptions. For example, the jackrabbit can dissipate heat from its large ears, while the kangaroo rat never needs to drink, getting all its water from the seeds it eats.

Inside a saguaro

Their huge bulk is supported by a strong but flexible cylinder-shaped framework of long woody ribs.

Along with old age, there are many things that can kill a saguaro: animals, lightning, wind, droughts, freezing... and of course humans. Livestock grazing from the 1880's until 1979 devastated some of the cactus forests. Seedlings were trampled or unable to find suitable places in the cattle-compacted ground. There's also the competition of introduced invasive species, plus vandalism and theft (for landscaping... since who wants to wait 60 years for a decent-sized cactus).

We talked for a while with a ranger. He said we had just missed a large rattlesnake that had been on the trail. He took us to go find it but it had already slithered off.

The rattlesnake had headed off in this direction, but we couldn't see it.

A saguaro without arms is called a spear. The arms are grown to increase the plant's reproductive capacity (more arms mean more flowers mean more fruit mean more seeds).

It was still fairly early in the morning but already QUITE warm (and this in winter! In the summer, it supposedly gets up into the 100's F). We debated briefly about doing a longer hike (there are some 130 miles of trails through the desert and mountains) but decided an easy drive and some shorter hikes might be better.

We set off along the Cactus Forest Drive, an 8-mile loop through a small section of the park.

The perils of the park... dehydration, heat stroke, injury, getting lost, snakebites, mountain lion or bear attacks... woodrats??...

The White-throated Woodrat (or pack rat) covers its nest tunnels with cacti and sturdy sticks as a means of keeping out predators. But it is also attracted to small objects that it finds lying around such as trash, toys, jewelry and even car keys!

That's going to hurt!

Clearly a seasonal flood wash

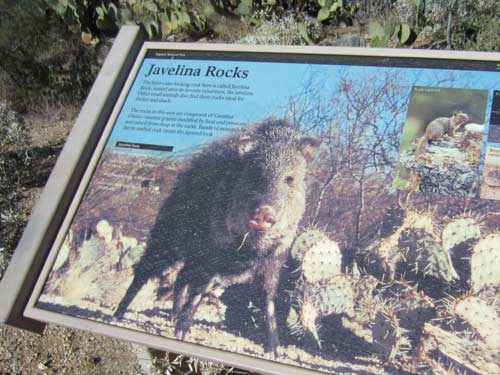

We stopped and walked around at Javelina Rocks, so named because of a favorite inhabitant. We didn't see any though.

Javelinas are not pigs but rather peccaries. Their name comes from their razor-sharp tusks (javelina is Spanish for spear). They weigh up to 60 pounds and have scent glands on their backs.

The rocks are composed of Catalina Gneiss, an ancient granite modified by heat and pressure and raised from deep in the earth.

There aren't just saguaro here; 25 other species of cacti can also be found.

The fruit of a Fishhook Pincushion barrel cactus...

... and the fesity spines that give it its name! Spines are actually just modified leaves.

This is called the Jumping Cholla because pieces of the plant can so quickly and firmly attach themselves to the skin that they almost seem to jump on you!

It's clear to see how easily a piece could break off.

The Teddybear Cholla almost has a soft, cuddly appearance (hence its name) in spite of its solid mass of spines that completely cover the stems.

Holes are made from birds, mostly woodpeckers, but many other types of birds, as well as bees, will move into old, empty holes. Insulated by thick walls, the holes are up to 20 degrees F cooler in summer and 20 degrees F warmer in winter.

Baby arms! Of course, this means the cactus is at least 60 to 70 years old.

Hmmm, some type of grass, I believe

A freeloader back in the car

Next we did the Freeman Homestead Nature Trail, a 1 mile roundtrip. It took us through many tall cacti, to the old homestead, through a long wash, then back through the desert. Handy informative signs lined the way.

Wow! Judging from the arms, this saguaro must be at least 150 years old!

A mighty perch

The Velvet Mesquite plays a vital role in the ecology of the Sonoran Desert. Many animals (coyotes, ground squirrels, peccaries, deer, jackrabbits) eat the pods; birds feed on the flower buds; the tree fixes nitrogen in the soil; it serves as protection to young cacti; it offers shade and protection for small mammals; etc.

The leaves have the ability to fold together to conserve moisture.

The Creosotebush (or Greasewood) is a prominent species in this desert environment. Although creosote bushes produce large numbers of fuzzy seeds, few of them are able to germinate. As such, it also reproduces by forming clonal colonies (much like aspens do). As the shrub grows, stems sprout up around the original stem. Eventually the central stem and branches die and rot away, leaving the surrounding newer stems to continue to grow. They may look like unique plants but are really just clones, all descended from one seedling. The process continues until the clone spreads across the ground in a circular or elliptical shape. Usually, a mound of sand accumulates in the central area. In the Mojave Desert near Lucerne Valley (California), one clonal colony, named King Clone, has a average diameter of 45 feet and has been dated to be 11,700 years old, having lived continuously since the last ice age.... making it one of the planet's oldest living organisms.

Desert Globemallow (or Apricot Mallow) is highly drought-resistant.

Safford Freeman and his family settled in this area in the early 1930's. The Homestead Act granted them 640 acres to farm, graze or mine. Here they built a 3-room adobe home.

The Freemans in 1936 (left to right): Safford, Kirk, Ben, Mary, Tom, Shorty, Dorothy, Jean and Bonnie

Their home in the 1930's...

... and all that's left of it today.

The start of the wash at the far end of the loop

The trail continued back along the wash.