It was still a bit windy when we got up. Originally we were going to spend another day here but instead decided to hit the road. We drove west, crossing over the mountains in Lincoln National Forest to White Sands National Monument. Our trip took us through a wide range of ecosystems... from desert scrub to mountains forests to expansive sand dunes.

There was snow at Cloudcroft Village (elevation 8,650).

What's that long white line beneath the mountains? That's the sand dunes!!

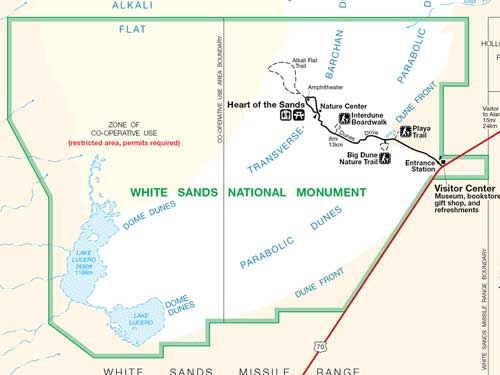

White Sands National Monument is located in the Tularosa Basin (Spanish meaning 'reddish reeds'). Wave-like dunes of gypsum sand cover 275 square miles, 40% of which is protected by the national monument. The remaining 60% lie in a government missile range... where the world's first atomic bomb was exploded.

White Sands is the largest gypsum dune field in the world, with a size of 10 miles by 30 miles. The green patch to the right is Lincoln National Forest.

In the early 1900's, commercial interests tried to mine the area for its resources. Fortunately they were unsuccessful due to the low market value of unprocessed gypsum sand. As a result, the area fit the description of what the National Park Service sought in prospective sites: economic worthlessness and monumentalism. It took 35 years, but finally 224 square miles of the area fell under government protection in 1933 when President Herbert Hoover declared it a national monument. The construction of the museum, residences and other structures were the result of the Works Progress Administration.

A commercial building from the 1920's

Click for a larger view

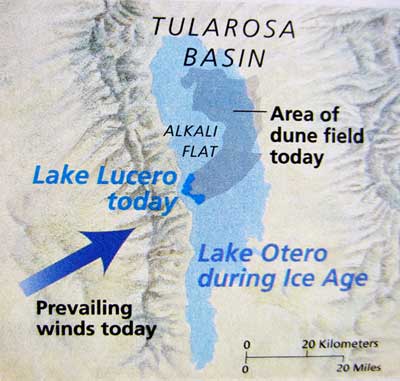

The dune field is less than 10,000 years old. During the last ice age (24,000 to 12,000 years ago), the climate was much wetter. Rain and snowmelt carried gypsum and salt into the Tularosa Basin from the surrounding mountains. This runoff settled in a 1,600 square mile lake called Lake Otero. As the ice age ended, the lake began to evaporate, changing into a playa (dry lake bed). Concentrations of crystallized gypsum (called selenite) formed beneath the clay and silt surface of the flat. When winds began to sweep the area, the dry air currents exposed these buried crystals. Freezing and thawing eventually broke them up into smaller and smaller pieces, finally turning them into sand. The tiny grains were picked up by the wind, moving a few inches at a time, to eventually form the dunes.

Lake Otero dried up around 4,000 years ago.

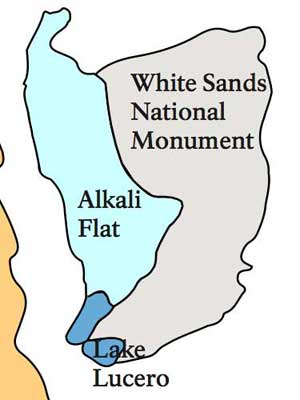

Alkali Flat is a dry lakebed which was once part of large Lake Otero. Lake Lucero was also once part of the ancient lake. It continues to serve as a sort of mini-Otero, still creating selenite crystals (from gypsum-laden rainwater that trickles down from the mountains) which then replenish the white sands of the dunes. It is named after the Lucero brothers, Jose and Felipe, who ranched in the area and took turns serving as a local sheriff.

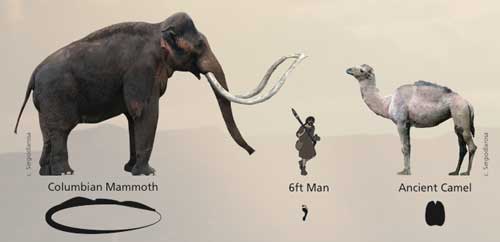

30,000 years ago, megafauna (basically big animals) roamed this area. The majority of the fossil tracks suggest they traveled along the shorelines of Lake Otero and across the surrounding wetlands. Once exposed from beneath the sand, however, the tracks weather rapidly.

Those are some big animals! Fortunately, they pre-date the arrival of humans in the area by about 20,000 years!

White Sands Missile Range is one of six national ranges that support missile development and test related programs for the army, navy, air force, NASA and other government agencies. It is the largest all-land military reservation in the US. The area was selected for several reasons: the land was cheap (and much of it was already government owned); the weather offers good visibility year-round; and the region was sparsely populated at the time.

In the 1940's, soldiers were allowed to practice tank maneuvers, even inside the monument’s boundary.

The range was established in 1945. One week later, the world’s first atomic bomb was detonated approximately 60 miles north of the national monument. The test was code-named Project Trinity. The explosion sent a multi-colored cloud 38,000 feet into the air and left a crater a 1/2 mile across and 8 feet deep. The intense heat fused the sand in the crater into a glass-like solid, which was given the name trinitite. After the explosion, the site was closed off for radioactivity until 1953.

Trinitite (also known as atomsite or Alamogordo glass) is usually a light green, although the color can vary. It is mildly radioactive but safe to handle. In the late 1940's and early 1950's, samples were gathered and sold to mineral collectors as a novelty. Any remaining pieces were bulldozed and buried by the US Atomic Energy Commission in 1953.

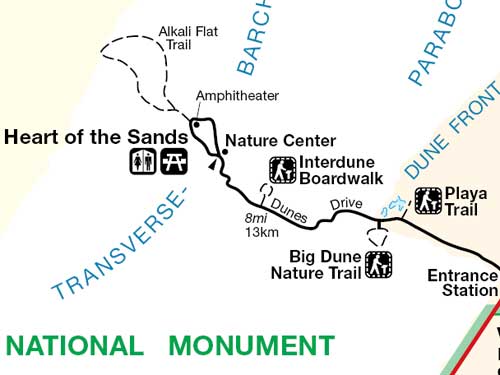

We stopped briefly at the visitor center then drove into the park. Our destination was the Alkali Flat Trail, the furthest one in the park.

The adobe visitor center was completed in 1938.

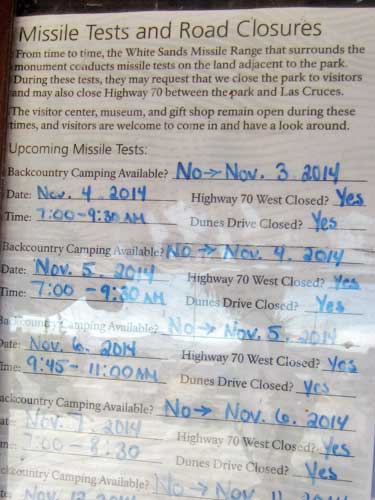

This notice was posted outside. Each year, the range fires around 900 missiles for testing, requiring park closures. Fortunately nothing was on the list for today!

It was hard to remember this was sand... not snow!

Alkali Flat Trail was a 4.6 miles loop trail. It leads through the Heart of the Sands over unbroken dunes that stretch for miles and ends at the beginning of the Alkali Flat, the edge of old Lake Otero. We weren't planning on doing the entire thing. We mostly just wanted to get a feel of the dunes.

A satellite image of the area. On the far lower right, you can just barely see the loop of the road. There is an obvious transition line between the sand dunes and the flat.

Heading out

The trail is marked, with each post visible from the previous and the next one.

Surprisingly, it wasn't just a uniform blanket of white. There were dunes and flat parts. There was soft sand and hard sand. There was light sand and dark sand. And the ripples came in all sorts of patterns!

Trudging up a dune

The highest dunes are approximately 60 feet tall.

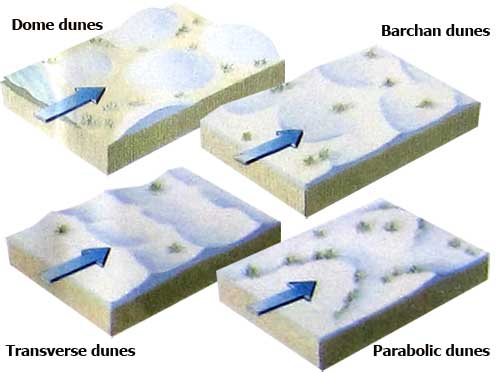

There are four types of dunes found here.

Two main factors are necessary for creating sand sheets and dunes: 1) an adequate supply of sand, and 2) winds strong enough and persistent enough to move the sand. In general, sand tends to accumulate near obstacles, such as a rock outcrop, vegetation, a small depression, etc.

This is taken looking straight down, so not very high up. But it's amazing how similar it looks to the satellite photo I showed at the start of the trail.

Remember, the grains are particles of gypsum, not silica.

There are five basic forms of gypsum: selenite (normally in crystal form, but ground up very fine here), satin spar, alabaster, rock gypsum (the most common form) and gypsite. Gypsum is actually rather heavy. Being expensive to transport, combined with this remote location, it's not surprising that early mining businesses failed.

Clumps...

... and sheets

This blue tint wasn't just shadow, ...

... it was actually the color of the sand.

Believe it or not, animals actually live out here. These are some mouse tracks.

This poor little insect wasn't so successsful.

The depth of the sand goes 30 feet below the interdunal surface. There are about 4.5 billion tons of sand, which is enough to fill 45 million box cars... for a train long enough to circle the earth at the equator over 25 times!

Some kind of facility sat beyond the monument's boundaries on the flat.

Along with the usual warnings of bring enough water, wear appropriate clothes, pack out your trash, what to do if a storm hits, etc, was also this: "The air space above the park is periodically used by military aircraft and for missile testing. Debris from testing occasionally falls into the park and gets buried by sand. If you see any strange objects, please do not touch them as they may still be able to detonate." Nice.