It was exceedingly windy all night and hadn't let up at all by the morning. Originally we were considering doing some hiking in the area, but seeing as it was difficult to even remain on our feet, we decided to head underground... with a trip to Carlsbad Caverns.

Windblown seeds danced upon the road in the millions.

Entering the Guadalupe Mountains

When we arrived, the wind was still extremely fierce. We fought our way into the visitor center.

Darren is about to lose his hat!

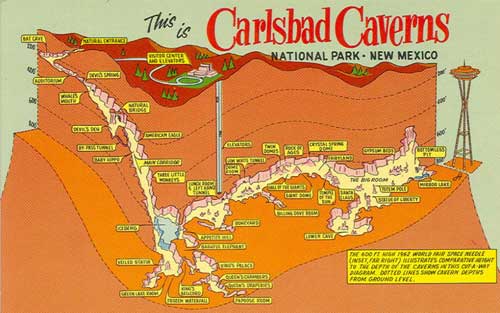

There are over 300 caves in these mountains and over 100 have been surveyed in this park alone. Three of them are open to the public, but Carlsbad Caverns is the most famous and easiest to walk through. It has electric lights, paved trails and even elevators. The other two, Slaughter Canyon Cave and Spider Cave, are undeveloped and require special tours. The area was first protected as a national monument in 1923 and became an official national park in 1930. The caverns get some 400,00 visitors every year. Most people come to see the Mexican free-tailed bats which inhabit the cave from are present from April/May to late October. Darn, missed 'em!

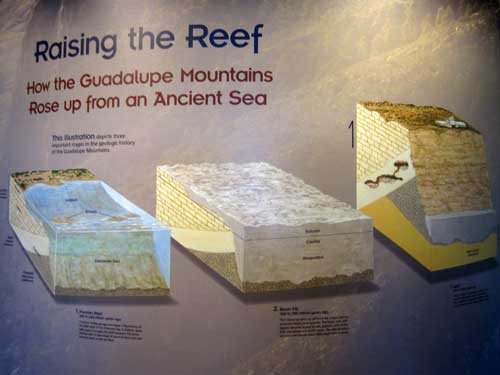

Carlsbad Caverns (named simply after the nearest town) is a limestone cave deep inside in a fossil reef known as Capitan Reef. Some 240 to 280 million years ago, this area was the coastline of a warm, inland sea. The reef was built of sponges and algae, not by coral like those of today. The water eventually receded and the coastline was buried by sediments, forming a limestone layer of rock over 1,800 feet thick, 2 miles wide and 400 miles long. It lay buried for tens of millions of years. Tectonic movement (20 - 40 million years ago) then uplifted the area almost 10,000 feet. Erosion weathered away the overlying younger sediments and the ancient reef was exposed.

90% of the world's limestone caves are created by carbonic acid. These types of caves are generally very wet with streams, lakes or even waterfalls in them. But there are no flowing rivers in any of the Guadalupe Mountains caves. That's because these caves were carved out by sulfuric acid instead, which is much stronger (and can carve much faster).

Sulfuric acid is formed by the oxidation of hydrogen sulfide (a colorless, poisonous, explosive gas with the smell of rotten eggs) in water. The hydrogen sulfide possibly came from nearby oil fields but it also occurs in volcanic and natural gases. So, while most caves were formed by surface water trickling down, these caves were formed by sulfuric acid moving up. It wasn't so much a case of the acid moving upward but rather as the Guadalupe Mountains uplifted little by little, the level of the water table dropped in relation to the land surface... causing the highly aggressive acid bath to drain away leaving a newly dissolved cave behind. Hence, the oldest caves are actually closer to the surface while the youngest caves are the deepest.

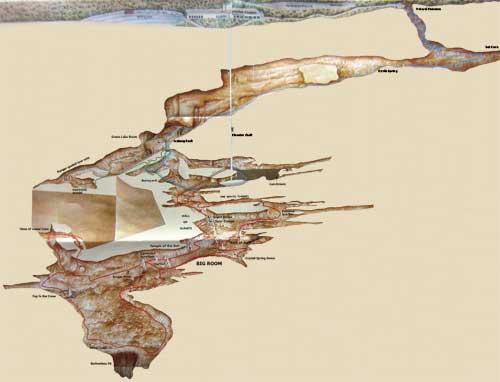

Side view. Click for a larger view

Cave formations (known as speleothems) begin to appear once the chambers become air-filled. Rain and snow percolate down through the limestone rock, picking up carbon dioxide. Each droplet of weak carbonic acid continues to dissolve and carry with it tiny amounts of limestone. When it reaches a cavern ceiling, some carbon dioxide escapes into the air and the water's ability to hold limestone in solution is reduced... so a tiny deposit of calcium carbonate (the chief component of limestone) is left behind. Year by year, drop by drop, the cavern decorations are slowly created.

In the case of Carlsbad Caverns, air began to enter the chambers with the collapse (and opening) of the natural entrance within the last million years. Climate affects how fast or slow speleothems grow. Today, few speleothems inside any Guadalupe Mountains caves are actively growing. This is a direct result of the dry desert climate. Most of those inside Carlsbad Caverns would have been much more active during the last ice age-up to around 10,000 years ago.

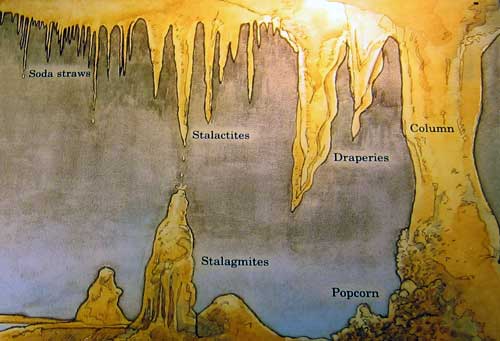

Growths from the roof downward are called as stalactites; growths from the floor upward are stalagmites. The slowest drips tend to stay on the ceiling long enough to deposit their mineral there; the faster drips tend to make some type of decoration on the floor.

It has always been my experience that one MUST go on a guided tour in order to visit any cave. But not here! There were indeed ranger-led tours offered to some of the amazing side caverns, but we were also allowed to do our own self-guided tour through most of the largest sections of the cave. So we opted to do it ourselves.

Click for a larger view

We braved the strong gusts of wind during the short walk out to the main entrance. A ranger explained a bit of how things worked and we were off... headed straight down into the giant, gaping mouth of the cavern into the darkness.

Jim White is given credit for discovering, exploring and promoting the cave as a boy. He eventually became a park ranger. One day while riding his horse looking for stray cattle, he saw a plume of bats rising from the hills. He went to explore and "found myself gazing into the biggest and blackest hole I had ever seen, out of which the bats seemed literally to boil". A few days later, he returned with some rope, fence wire and a hatchet. With a makeshift ladder and a homemade kerosene lantern, he began the first of many explorations.

James "Jim" Larkin White (1882 - 1946)

Still going down

There were glowing informative signs along the way.

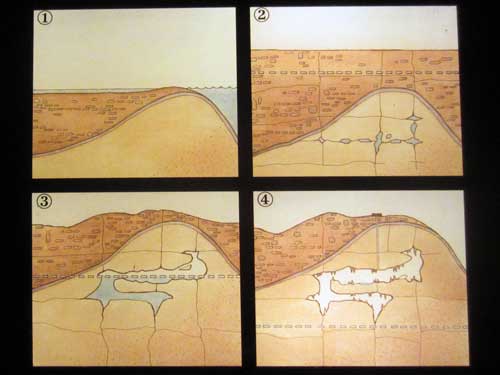

ONE - 250 million years ago: Marine plans and animals built a limestone reef along the edge of an inland sea.

TWO - 60 mya: Hydrogen sulfide gas (from deep oil and gas deposits) and water formed sulfuric acid which dissolved cavities within the limestone.

THREE - Three mya: As more limestone dissolved, cavities enlarged. Water slowly drained from the cavern. Roof sections collapsed.

FOUR - Recent: Stalactites, stalagmites and other cave decorations formed as limestone-laden ground water dripped into the air-filled cavern.

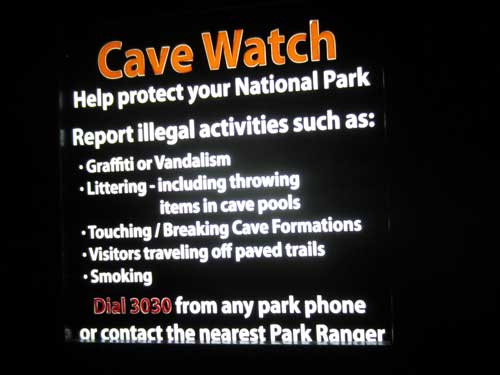

These features rest in a pool of water called Devil's Spring. It's not actually a spring but rather a pool fed only by dripping water. No streams flow in or out of it, so contaminants can not be washed way. Litter is very harmful: the copper in coins turns the rock green; decaying food discolors the water and causes a bad smell.

A park ranger attempts to clean a pool contaminated with coins.

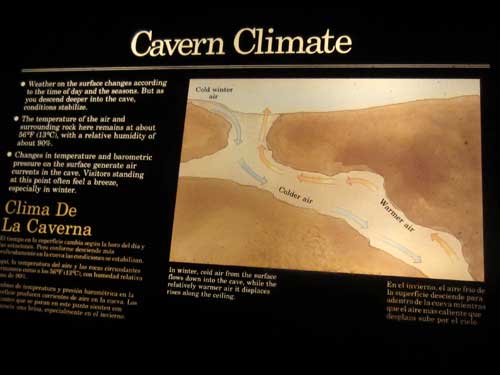

Weather on the surface changes according to the time of day and the seasons. But deep in the cave, conditions are stable... a constant 56 degrees F and a relative humidity of about 90%. Sometimes changes in temperature on the surface (especially in winter) can generate air currents, creating a slight breeze as cold air from the surface flows down into the cave while relatively warmer air rises out along the ceiling.

Going all the way down!

There actually very few people in this section. Almost everyone had signed up for the giant tour groups. There were rangers along the way so we took the opportunity to ask questions. Why, for example, do people sign up for the crowded tours? Well, mainly because the tours go to places in the cave that are closed off otherwise. Why are they closed off? Primarily because of graffiti, but also because of people urinating and defecating all over the place. Apparently once someone had even used a t-shirt to wipe afterwards and left that as well. Eew!

This formation of draperies is aptly named the Whale's Mouth.

Speoloethems (cave formations) form when groundwater containing calcium bicarbonate solution seeps into the cave. When the solution becomes exposed to air, carbon dioxide is released and calcite is deposited. Over time, these grow into the different shapes and textures we see.

Speleothems take various forms depending on whether the water drips, seeps, condenses, flows or pools. Some common types are:

Dripstone is calcium carbonate in the form of stalactites or stalagmites:

- Stalactites hang from the ceiling (it has to hang on TIGHT)

- Soda straws are thin, hollow stalactites

- Stalagmites point up from the ground beneath the stalactite that drips down and creates it (it MIGHT reach the ceiling one day)

- Columns result when stalactites and stalagmites meet or a stalactite reaches the floor

Flowstone is sheet-like and found on cave floors and walls:

- Draperies or curtains are thin, wavy sheets hanging downward

- Cave bacon is a drapery with colored bands

- Stone waterfalls simulate frozen cascades

Along with Cave crystals and Speleogens (formations created by the removal of bedrock rather than as secondary deposits), there are also other interesting formations such as Cave popcorn (small, knobby clusters of calcite and Calcite rafts (thin accumulations of calcite that appear on the surface of cave pools).

Speleothems made of pure calcium carbonate are a translucent white color, but often they are colored by minerals such as iron, copper or manganese, or may be brown because of mud and silt.

Cave popcorn

Flowstone

A column

This is just the tip of Iceberg Rock, a 200,000-ton slab that broke loose from the cavern wall and fell to the floor.

Passing by the Green Lake Room

Cave popcorn

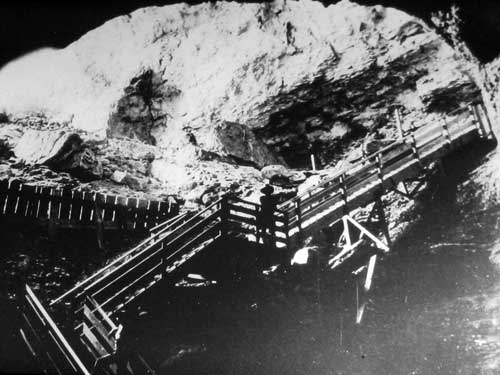

The cavern became a national attraction in the 1920's. However, back then there were no elevators, paved trails or good lighting.

Some of the old stairs

In the Boneyard, the limestone is riddled with holes. It reminded the early explores of old bones.

When the cave was developing, weakly-acidic groundwater permeated joints or cracks in the limestone. Holes formed where acid dissolved the rock.

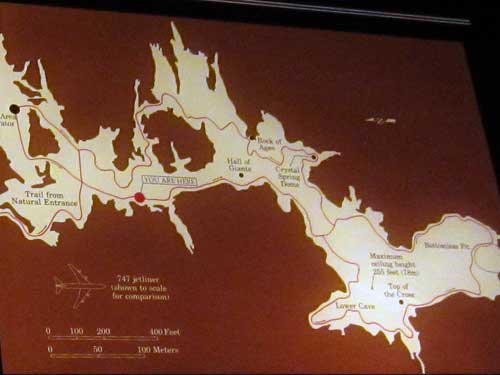

We then entered... The Big Room. It is the largest known natural limestone chamber in the Western Hemisphere. The chamber is almost 4,000 feet long, 625 feet wide, and 255 feet high at the highest point. The floor space is over 600,000 square feet (about 14 football fields) and the path is a mile and a quarter long.

Click for a larger view