My friend, Ron, and I spent a amorning at the Valley Forge National Historical Park in May 2007. Valley Forge was the first state park of Pennsylvania in 1893 and became a national park in 1976.

No battle was fought here. Valley Forge (named for an iron forge along Valley Creek) was a military camp situated 20 miles northwest of Philadelphia, where the Continental Army resided in 1777-8 for their third winter encampment during the American Revolutionary War against the British. The first three months were filled with great suffering (starvation, disease, supply shortages and a severe winter), but fortunately in the three months that followed, the army was revitalized, both in morale and in fighting capabilities.

In early December 1777, General George Washington sought a secure location for the army's winter quarters. Several locations were considered but Vally Forge was chosen because it was located between the Continental Congress in York, supply depots in Reading, and British forces in Philadelphia. In many ways, it was not ideal. It was unable to protect southern Pennsylvania and was also within easy striking distance of the British (who were well-provisioned). But the dense forests made it defensible, and there were also rivers and plenty of timber to build with.

Washington and his 12,000 men arrived on December 19, 1777. Only about one in four of them had shoes after the long marches. They promptly set about to building huts. But the supply situation was a far more serious threat than the enemy army. Conditions were crowded and blankets were scarce. Hundreds of horses either starved to death or died of exhaustion. Soldiers deserted in great numbers and officers resigned. Snow made it impossible to keep dry and caused diseases (such as typhoid, typhus, smallpox, dysentery and pneumonia) to fester. Many soldiers were also still wounded from previous battles.

After the horrendous winter, the Continental Army learned that France had become an ally. When they heard the British had left Philadelphia, they departed from Valley Forge on June 19, 1778, and retook the city. Washington maintained that the events at Valley Forge made the Continental Army stronger and eventually able to win the war.

George Washington (1732 - 1799) was one of the country's founding fathers, served as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, presided over the convention that drafted the United States Constitution, and became the first President of the US (1789 - 1797).

Our first stop were some reconstructed cabins that served as huts for the soldiers.

Huts line the original street of Muhlenberg's brigade.

Following their arrival on December 19, 1777, the men immediately set to work building huts for shelter. Each hut was to be 14x16 feet, 6.5 feet high, with a door next to the street and a fireplace in the back. In spite of these orders, the huts varied drastically in terms of size, location and materials used. Men from different regions used the building techniques they were familiar with.

A bit far off the road!

Inside one of the huts

Nearby, some "Continental soldiers" were having lunch.

A set of cooking gear was issued to every six or eight men. This included a kettle, cooking forks and spoons and often a water bucket. Soldiers had to provide their own plate (usually of wood or pewter), utensils and cup.

The uniform of the American Revolutionary soldier consisted of:

- a hat, usually turned up on one or three sides

- a shirt of linen or cotton

- a black leather stock worn around the neck

- a wool coat with the collar, cuffs and lapels of a different color

- a waistcoat or vest of linen or wool

- a pair of trousers, either breeches or overalls

- stockings

- leather shoes

Various items they would have carried with them... with the jacket of an Artillery man

Uniforms were actually quite important. Back then, battles were fought with black-powder weapons which would produce enough smoke to make it difficult to see more than a few yards.... eventually obscuring the battlefield. In order to distinguish between friend and foe, bright colors were used. Commanders could see these colors through the haze and then give new fighting orders. The British mostly wore red; the French had white and blue; and the Americans, browns. Unfortunately, there was a shortage of brown cloth, so uniforms had to be brought in from France... which were mostly dark blue with red accents. You take what you can get!

The flintlock had been around since the early 1600's. (Note the piece of flint)

An important weapon was a muzzle-loading musket, often with a bayonet. When a piece of flint struck steel, a spark was created, which in turn set off black powder in the barrel of the gun. It could fire a single shot ball or multiple projectiles (like a shotgun). A trained soldier could reload and fire about four times a minute.

This type of gun had many problems though: it didn't work in wet weather because damp gunpowder doesn't ignite (in general, armies avoided battles when it was raining); misfires were common (from a dulled piece of flint that didn't cause a big enough spark) as were accidental firings (from residual burning embers when having to reload so quickly, or having your neighbor's spark set off your powder).

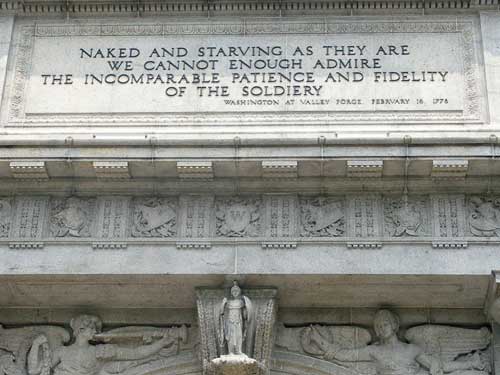

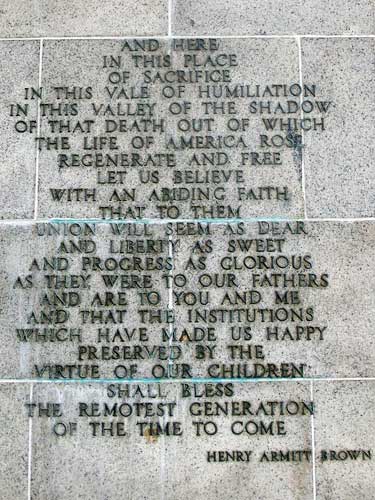

The National Memorial Arch was authorized by Congress in 1910 as a tribute to George Washington and his army.

The arch was in need of major repairs by the mid-1990's and the preservation was funded mainly by the Freemasons of Pennsylvania. Washington was a Freemason and served as master of his lodge at the same time he was president of the US.

Next, was a stop at a statue...

Brigadier General Anthony Wayne (1745 - 1796)

Brigadier General Anthony Wayne commanded the First and Second Pennsylvania Brigades. A brigade contained about 800 men. With sixteen brigades stationed here, that added up to a lot of food required to feed them... 34,577 pounds of meat and 168 barrels of flour per day! It was up to their home states and the Continental Congress to supply them with food, clothing and equipment. Shortages varied widely between the regiments. Any number of misfortunes, such as spoilage, bad roads or capture by the British, could prevent supplies from reaching camp.

When food ran so low that mutiny seemed imminent, Wayne led an emergency foraging raid to round up all the cattle they could find (and destroy those they couldn't bring with them). Cattle owners tried to conceal their herds in the pine woods, but the general was successful in spite of their attempts.

Dinner has arrived!

Wayne's military exploits and fiery personality earned him the nickname of Mad Anthony.

The headquarters house was the center of military activity. From here, General Washington and his staff directed military operations from Georgia to Maine.

This land was originally owned by William Penn, who gave it to his daughter Letitia Penn Aubrey and her husband William in 1701. They gradually sold off the property, with the last piece going to three men in 1730 who built the Mount Joy Forge (later known as Valley Forge). In 1757, it was purchased by a prominent Quaker named John Potts. His son, Isaac, built a large stone house along the creek... which Washington rented to serve as his military headquarters.

For 6 months, this area was filled with activity... express riders from Congress, guards, civilians, couriers rushing out with new orders, foreign officers, etc.

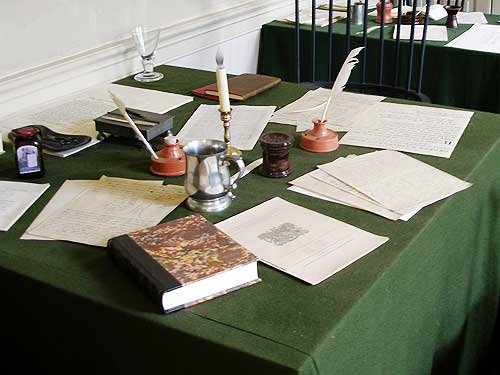

The office. In the afternoon, the papers were cleared and the tables pushed together for lunch and discussions. The tables would be pushed away at night to make room for sleeping.

Aides were required to make three copies (all handwritten back then!) of each official document.

There were various bedrooms for officers, aides and guests. Up to 25 people at a time would be living in the house.

As the saying goes, "Washington slept here"... although in this case, he really did.

The kitchen

The barn

This railroad station was built in 1913 to service visitors to this historic site. Trains were still more popular than private cars at this point. The tracks were first used in 1832 to meet the demands of industrialization.

This white tail deer would not have faired well with Mad Anthony!

return • continue