This was a hike on the North Foothills Trail, organized by OSMP (Open Space and Mountain Parks, run by the city of Boulder). Our guides were naturalist Lynne Sullivan and geologist Sue Hirschfeld. Entitled "Rattlesnakes, Rarities and Railroads," the hike took us through the fragile landscape into the environmental, cultural and geologic past of north Boulder.

This area is known as an ecotone, a transition area between two biomes (in this case between prairie and mountain ecosystems). This leads to enormous biodiversity... actually, this stretch happens to be the most diverse spot in the entire inland USA, and fortunately it's been protected since the 1890's. The city of Boulder currently protects some 45,000 acres of open space, including this special Habitat Conservation Area.

Lynne and Sue

Our first point of interest was Silver Lake Ditch which was built by pioneers in 1888. Back in 1859, gold was discovered in Denver. This brought in a wave of folks seeking their fortunes. But for all those digging for the shiny metal, there had to be farmers to feed them... and to farm, there had to be water, and for water, there had to be irrigation ditches. Silver Lake Ditch (originally called "Maxwell and Oliver’s Ditch” after its constructors James P. Maxwell and George Oliver) was the last one to be built and drew its water from the Silver Lake Reservoir (fed by meltwater from Arapaho Glacier).

Map of the long ditch. We are at the red arrow (Click map for a larger view)

The ditch was quite an extensive project. Bringing water through Boulder Canyon required wooden flumes along the cliffs.

At first glance, we were worried these were highly invasive New Zealand mud snails, which were first discovered in this area in 2005. But fortunately these seemed too large.

We continued on to our next stop... a prairie dog colony. Prairie dogs are considered a "keystone species." 70 other animal species depend on them for their survival, both as a food source and/or for using their burrows. There used to be billions of prairie dogs here at one point, but now 98% of their habitat is gone due to housing, agriculture and highways. As a result, other species have either suffered or become extinct in the wild, such as the black-footed ferret.

Prairie dog colonies also serve to keeps grasses short. Generally, the colony slowly shifts as the animals move in search of new vegetation. Unfortunately this is no longer possible since they are forced to live in tiny, closed-off pockets. As a result, they tend to decimate an area. This proved to be a good thing during the last large fire here in 2006. The barren patches of land actually stopped the fire from spreading...

... Unfortunately the area also contains many yuccas. When their roots caught on fire, they turned into small exploding rockets that shot up and over the highway, thereby spreading the fire even further.

Prairie dogs don't need to drink; they get all the water they need from vegetation.

A sample of an overgrazed patch of land

Some seemingly harmless yuccas

A coyote wanders through prairie dog territory.

While it may not necessarily look like it, the landscape tells of great floods. Cemented boulders, gravel-capped hills, terraced landscape and landslides help us piece together the stories of the past.

Sue points out some evidence.

Large sediments (such as this cemented rock) require sufficient energy (hence a LOT of water) to transport them.

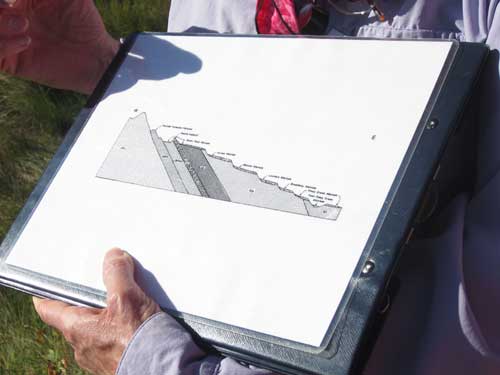

Click for a larger version of the rock diagram

This is where we are now. Note how gravel caps the hills, preventing erosion.

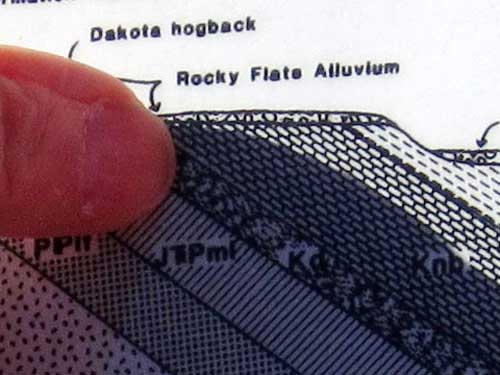

The Dakota Hogback is a long ridge along the Rocky Mountains that runs from southern Wyoming into northern New Mexico. In the Boulder area, it is the first line of foothills. Its name comes from the Dakota Formation, the sandstone that underlies it. It was formed some 50 million years ago, when the modern Rockies were created.

We continued on to the next part of our hike... the railroad. In 1881, the grade was constructed by the Boulder & Middle Park Railroad and Telegraph Company, but the tracks were never laid. Prominent investors were Charles G. Buckingham (a prospector and a banker) and James P. Maxwell (whom we've already learned about from the Silver Lake Ditch. He was also a state senator).

To the left of the trail is the path of the never-completed railroad. Note the indentation in the hill.

The approximate plan for the railway

Lynne then talked about some of the unique flora of the area, such as a large clump of Big Bluestem grass. Big Bluestem is normally found hundreds of miles away down in the prairie where it can get the moisture it needs. This spot is located in a depression carved out by a landslide. The clay soils form a water barrier underground... hence a perfect spot for the grass.

The hills in the background are part of the Dakota Hogback.

Big Bluestem grass

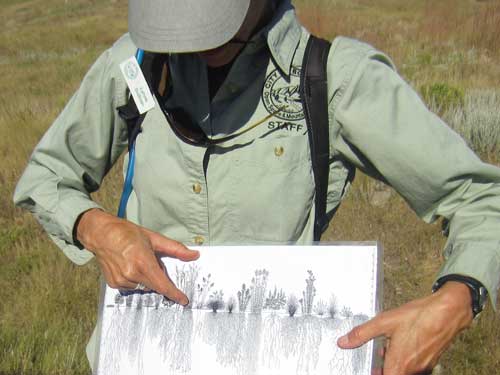

Tiny plants and grasses can have roots up to 14 feet deep. (click for a larger version of the diagram)

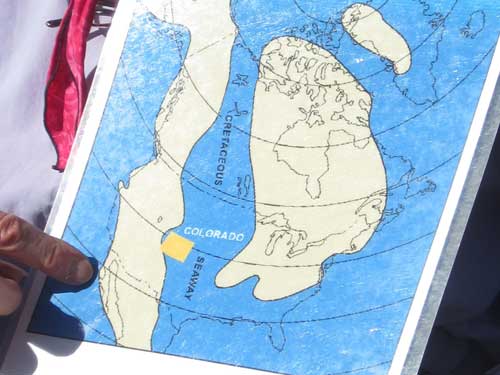

Sue pointed out some ancient and recent landslides and then went on to discuss the history of the rocks. 100 million years ago, this area was covered by a large inland sea. Then about 70 million years ago, the Rocky Mountains began to push upwards. As a result, our hills also contain a lot of limestone and shale... and ocean fossils.

This depression is the result of a giant landslide. Being as this entire area was once just mud on the banks of the sea, it tends to still be somewhat 'slippery.'

Photos of this area from the recent flood of 2013

Our steep mountain slopes also give us more rain than other nearby areas.

We continued on...

This is the path of an old game wall.

Some of these walls date back to as far as 3800 BC. Early pioneers thought they were fortifications used for territorial defense. But today, evidence points toward their use in hunting animals in open landscapes. Built along natural slopes, these slight walls helped hunters drive large game animals (such as sheep, deer or elk) toward other hunters who waited concealed with weapons.

While these cones may look like small volcanos (especially Haystack Mountain on the far left), they are actually a flood-washed structure that used to be part of Table Mountain. Gravel on their tops protects them from erosion.

We stopped along the ridge to explore more geology and flora.

The sedimentary layers of an ancient ocean floor

Pieces of Smoky Hills shale littered the ground.

Shale is a sedimentary rock largely made of clay.

Searching for fossils

Fish scales

A tiny shell

Plants have to be highly specialized to survive in this difficult environment. Due to all the shale, they also have to deal with selenium-rich soils.

Bell's Twinpod is very rare. It is only found here and in two other local counties. It has a five year lifespan.

It was then time for us to turn back and retrace our steps.

A clear view of the old railroad grade

Dung beetles infiltrating a pile of bear scat

There are over 100 species of grasshopper in Colorado. This is the large Two-striped grasshopper.

A Colorado Soldier Beetle rests on some Curlycup Gumweed. The sticky white sap is meant to prevent ants from climbing up from underneath and stealing the flower's nectar.

A local crew works hard at removing teasel.

While it may look pretty in the summer when it is blooming, teasel is highly invasive. Why is this bad? Because it creates a monoculture, wiping out other plants that local species may depend on.

The heads are cut off with the seeds and left to die in the heat of plastic bags. The stalks are left to compost back into the land.

We now got to the final part of our hike... rattlesnakes. Unfortunately (or fortunately, as some may say) we didn't actually stumble upon one. So we had to content ourselves with pictures and stories.

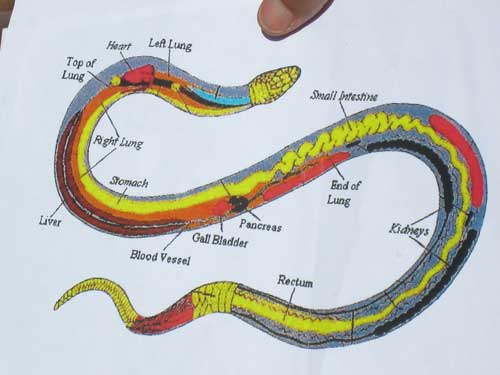

This is the inside of a snake. All the organs are long and skinny. They have only one main working lung, and many of their organs are able to move around (which is helpful when swallowing large prey).

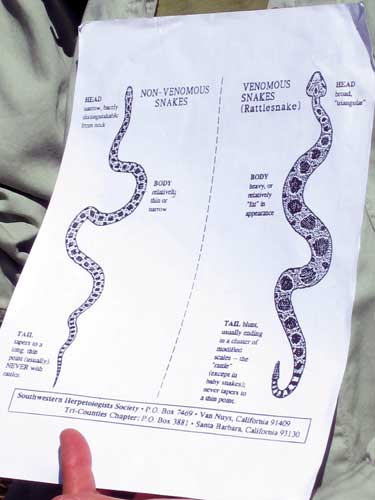

This is a comparison between a bullsnake (left) and a rattlesnake. Bullsnakes will often pretend to be rattlesnakes to scare off potential enemies. They will even coil up and shake their rattleless tail so that nearby dry grass will rustle.

Lynne demonstrates how male rattlesnakes fight over territory. Now, one might think that they would simply strike and lethally bite each other. But if that were the case, odds are we'd quickly have no more male rattlesnakes. So instead they have evolved to solve their differences via an odd wrestling match using their upper bodies, with the loser eventually getting pinned to the ground.... resulting in male snakes surviving to pass on their genes.

Photo of a rattlesnake that Lynne passed around

This is a photo of a rattlesnake that I took the week before on one of the local trails! This snake was VERY unhappy with me! Suffice to say I didn't linger very long.