DEATH VALLEY (Day 10 - part 3)

Our next stop was Zabriskie Point.

Christian B. Zabriskie (1864-1936) was vice president of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and oversaw the operations in Death Valley during the transition from mining to tourism. By the 1920s, mining had slowed and the company began to look for other uses of the land. The Furnace Creek Inn was opened in 1927 with great success. As more and more tourists arrived, the need to protect the area became obvious, and in 1933, this area became a national monument (and then upgraded to a national park in 1994).

3 to 5 million years ago, lakes filled the long mountain-rimmed valley. Fine silt and volcanic ash washed into the lake and settled to the bottom. It created a thick deposit of clay, sandstone and siltstone. These level layers were then folded and uplifted and tilted due to seismic activity, and then exposed by periodic rainstorms into the strange shapes before us.

The top black layer is lava that oozed out onto the ancient lakebed. The colors are from minerals such as borax, gypsum and calcite.

Continuing back up the valley...

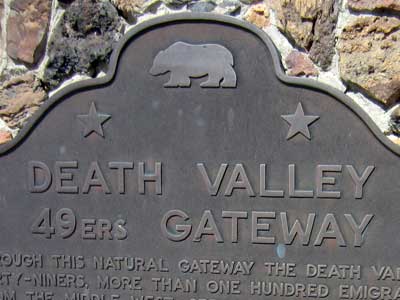

State registered landmark number 442. This is where the Bennett-Arcan party entered the valley in 1849, as a part of over 100 immigrants. From here, they split up... with the Bennett-Arcan group going south over the salt flats, and the rest going north to the sand dunes find a way out of the deadly valley.

Ruins from the old Harmany Borax Works company village

Next stop... the Harmony Borax Works.

Remains of the mine

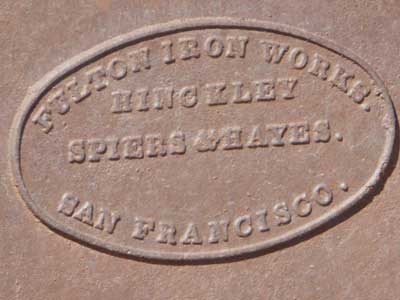

The mining of borax (or white gold) here began in 1882. Harmony Borax Works was one of the area's first borax operations. It operated from 1883-8. Built by San Francisco businessman William T. Coleman in 1882, the plant refined "cottonball" borax found on the nearby salt flats. The high cost of transportation made it necessary to refine the borax here rather than carry both it and waste to the railroad 165 miles across the desert. It closed due to financial problems and numerous competing borax discoveries on other (easier) parts of California.

As mining became more modern, huge open-pit and strip mines began to destroy the landscape. In 1976, a law was passed which closed the park to prospecting, although privately-owned mining claims still exist.

(left) Scraping the borax ... 1892 photo of the closed borax works and company village

Chinese laborers scraped the borax off the salt flats and carried it on a wagon to the refinery. They earned $1.30 per day... minus the cost of lodging (often crude shelters or tents scattered across the flat landscape below us) and food they bought at the company store.

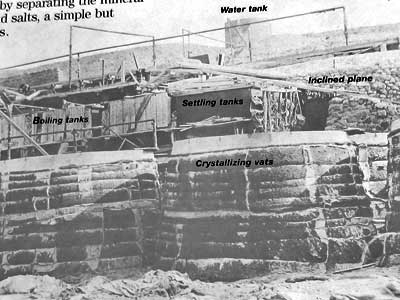

Borax was refined by separating the mineral from unwanted mud and salts. It was a simply but time-consuming process. Since borax will not crystallize at temperatures above 120 degrees F, operations had to stop during summer. To keep the crystalizing vats cool the rest of the year, workers had to wrap them in water-soaked felt padding.

The plant in 1900, 12 years after operations ceased

The surrounding landscape

View of the company village ruins

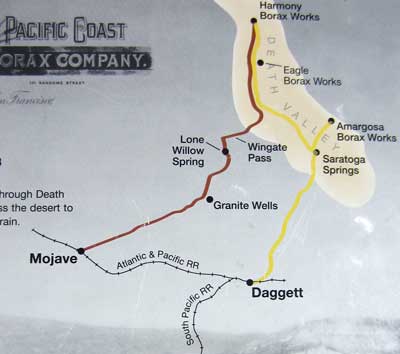

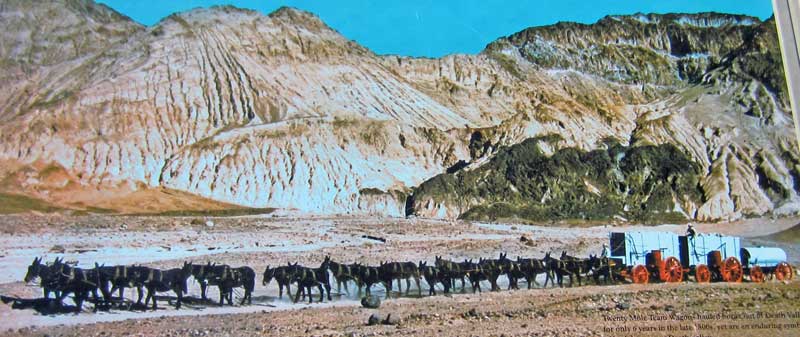

In order to get the processed borax to the closest railroad, large 20-mule teams hauled double wagons across the Mojave Desert. The mules pulled loads up to 36 tons, including 1,200 gallons of drinking water. The rear wagon wheels were up to 7 feet high and the entire unit (with mules) was over 100 feet long.

A 20-mule team at the Harmony Borax Works in 1885.

"20 mules" didn't always have to be exactly 20. It could vary more or less.

We continued retracting our path north up the valley. The day slowly got warmer.

return • continue