DRIVE HOME (Day 26 - part 2)

I left Sego and headed back onto the highway toward Colorado.

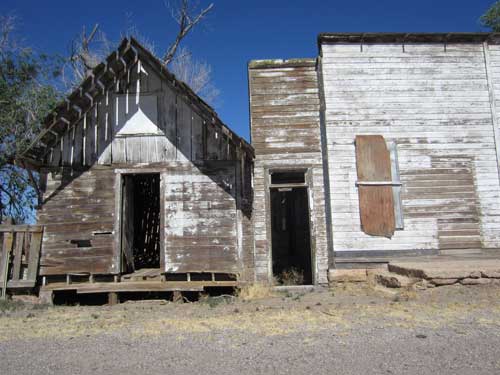

Thompson is the 'big town' close to Sego. This is the old schoolhouse from 1907.

Parts of it looked as abandoned as I imagined Sego once was.

This entire fence was covered with pelvic bones... I'm hoping from deer!

Heading due west

Before the system of numbered highways was created in the 1920's, the US relied on an informal network of roads. But even once interstate highways began to appear, Colorado's high mountain passes were too challenging, so most paths crossed the Rocky Mountains at easier spots in Wyoming or New Mexico.

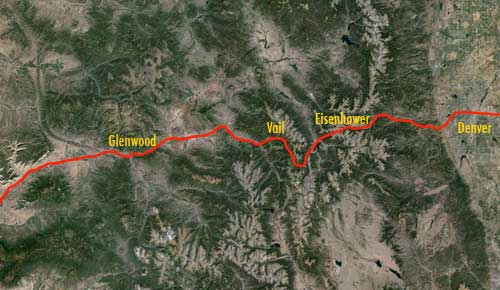

Interstate 70 (I-70) stretched from Maryland and ended at Denver. Continuing the highway west by building a mountain corridor was considered too difficult and too expensive. For years, Colorado officials negotiated with Utah officials, who would be required to continue the highway through the mountainous terrain in the eastern part of their state. After many years, however, a plan was finally agreed upon in 1955. Planning for the 144-mile route began in the early 1960's. It would encounter several difficult challenges: Glenwood Canyon, Vail Pass and the Eisenhower Tunnel.

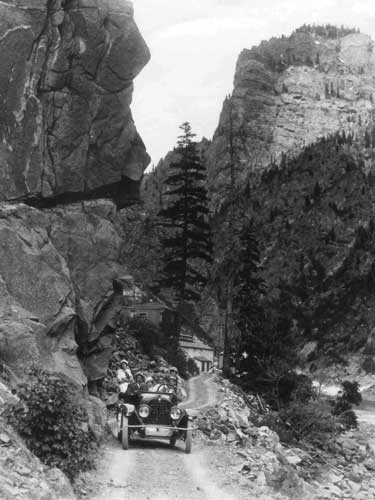

Even before the highways, railroads have used Glenwood Canyon since 1887. The Taylor State Road was completed in 1902, and the first paved road, US Highway 6, was built from 1936 to 1938. This stretch of road, however, was considered one of the most dangerous in the state due to frequent head-on collisions and sharp curves that, when icy, would result in vehicles sliding into the Colorado River.

Taylor State Road, 1914

Construction began in the 1960's but was soon halted due to environmentalist protests. So the original plans were scrapped and work began on a new design that would minimize impact to the fragile canyon environment. The new design was approved in 1975, but again, construction was halted by protests until 1981.

One major complication was the need to build a 4-lane highway without further destroying the canyon or disturbing the operations of the railroad. The solution: two separate tracks, one above the other. A portion of the project also included repairing the river bank from damage caused by the first highway. The final design included 40 bridges and viaducts, 3 tunnels and 15 miles of retaining walls. As many as 500 highway workers were employed in the canyon each day.

A 12-mile section of road was finally completed in 1992. At a cost of $490 million, this was one of the most expensive rural highways per mile built in the US.... 40 times the average cost per mile predicted by the planners of the Interstate Highway system.

The impressive Glenwood Canyon split-levely highway

For lunch I stopped at the Eagle Diner... in Eagle, Colorado. It was a charming little 1950's style place.

I wanted to be traditonal, with a vanilla milkshake...

... fries, and a (black bean veggie) burger. Hey, I did my best as a vegetarian.

Entering the Rocky Mountains

Vail Pass was not a traditional way over the Rockies. The most common westward route was over Shrine Pass, located a bit to the south. But in 1940, the construction of US Highway 6 created a new way. However, US 6 had a distinctive 'V' shape which the new planners of I-70 felt they could shorten by about 10 miles. This was all well and good... except that the new road would run directly across the federally protected lands of the Eagles Nest Wilderness. After the US Secretary of Agriculture refused to grant an easement, the engineers had no choice but to follow the existing route across Vail Pass.

One of the challenges of this portion was all the wildlife that roams this area. Large fences were built to prevent wildlife from crossing the freeway and direct them to one of several underpasses.

Approaching Vail Pass, elevation 10,666 feet

Continuing on

Instead of following the path along US 6, engineers recommended tunneling under Loveland Pass to bypass the old road's steep grade, hairpin curves and 11,992-foot elevation. The Eisenhower–Johnson Memorial Tunnel is a dual-bore, four-lane tunnel that crosses the Continental Divide at 11,158 feet. The westbound bore is named after Dwight D. Eisenhower (the president for whom the Interstate system is also named) and the eastbound bore is named for Edwin C. Johnson (a senator who lobbied for an Interstate highway to be built across Colorado.

Construction on the first bore began in 1968. The project suffered many setbacks and went well over time and budget. One of the biggest problems were fault lines that began to slip during construction, leading to collapses. Despite the best efforts of engineers, three workers were killed boring the first tube, and four during the second. It was also discovered that boring machines couldn't work as fast at such high elevations, which significantly slowed the progress. The project was only supposed to take three years but didn't open until 1973. The second bore was started in 1975 and finished in 1979. The initial cost estimate for the Eisenhower bore was $42 million; the actual cost was $108 million. The cost for the second (Johnson) bore was $102.8 million. Not included is about $50 million in other construction expenses.

Upon completion, it was the highest vehicular tunnel in the world. The tunnel is the longest mountain tunnel (just under 1.7 miles) and highest point on the Interstate Highway system.

As an interesting side story, the tunnel unintentionally became part of the women's rights movement. Janet Bonnema had been given a job as an engineering technician. However, after 18 months, she had still not entered the tunnel in order to do her job recording measurements, collecting rock samples and producing technical drawings. Apparently there was strong opposition to a woman entering a construction site, so much so that workers threatened to walk off the job if she did. But in 1972, she did. Several workers did indeed walk off the job, but most returned the next day.

Janet Bonnema

The tunnel has a command center with 52 full-time employees to monitor traffic, remove stranded vehicles and maintain generators to keep the tunnel's lighting and ventilation systems running in the event of a power failure.

All downhill from here!

The familiar foothills of Boulder

I arrived home safely in the late afternoon. Total miles... 3,040. Another trip filled with amazing memories... completed.

return • continue