CAPITOL REEF (Day 22 - part 3)

Next I visited a few of the historic sites. The 200 acre Fruita Rural Historic District is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Gifford farm has been renovated and refurnished to its early 1900's state. The original home was built in 1908 by Calvin Pendleton who lived here for 8 years. Originally, a ladder OUTSIDE led to the bedrooms upstairs. He sold the place to Jorgen Jorgenson, who in turn sold it to his son-in-law, Dewey Gifford, in 1928. They lived here for 41 years. They added a separate kitchen in 1946, a bathroom in 1954 (until then it was a two-hole outhouse), and got electricity in 1948.

Calvin David Pendleton was the only polygamist in the community.

Clavin's first wife, Mary, died not quite one year after their marriage and just one month after their first child was born (who died just before his first birthday). Calvin was married to his second wife, Susannah, for 17 years before he also married Harriet. He was 38 and she was 25. Calvin maintained two separate households for about 7 years: Susannah in Payson and Harriet in Salt Lake. Around 1894, he moved both families to Fruita. By then, the US government was not only preventing new polygamous marriages but also dissolving existing ones. But Calvin had entered into polygamy prior to the laws of 1890. Like many others, he was now faced with a problem: the church and personal morals did not approve of divorce, but the government did not approve of his lifestyle. Thus, Calvin may have moved his families to this remote area to avoid prosecution. In 1898, he bought 37 acres from Nels and Mary Jane Johnson, putting the deed in the name of his first wife. Calvin built two homes in Fruita, one for each of his wives. He and his sons also built a barn, a granary, a smokehouse and planted fruit orchards. Calvin died at 87 years old. He had outlived all three of his wives as well as 12 of his 15 children.

Jorgen and Annie Jorgenson

The Giffords were the last residents of Fruita, selling their home and land to the National Park Service in 1969. The kitchen was converted to a store, selling reproductions of household items used by the early Mormon pioneers. They are all handmade locally.

Family histories

The Giffords raised dairy cows, hogs, sheep, chickens and ducks. They also ran cattle in the desert and had a productive vegetable garden and orchard. Water had to be carried from the Fremont River.

A washing and wringing machine

In the old days, people would use a rock and nearby stream to pound laundry clean. Then came the ribbed scrub board, designed to make life a bit easier. The first washing machine to use a drum was patented by James King in 1851, although people had been filing for 'washing and wringing' machines since the 1790's. It was still hand-powered but eventually rudimentary gasoline engines could be used. In 1874, William Blackstone designed a machine for indoor use. The first electric-powered washing machine came along in 1908, and by the 1930's, enclosed spin dryers replaced the dangerous power wringers.

An old shed...

... complete with repairs using old license plates!

A 1936 Ford

An old wagon

Dewey Gifford shares some recorded thoughts of his 40+ years of living in Fruita.

"My name is Dewey Gifford, and I was a farmer and rancher in Fruita from 1928 until 1969. For much of that time, we had no running water, electricity, or telephone. There was little cash to be had from farming, so I had to be away when I was young. I worked on the state roads, herded sheep, and ran cattle in the South Desert. But the most pleasant memories I have were those of family, farming and friends here in Fruita. Until 1940, we used all teams and horse-drawn implements, mostly for growing and cutting alfalfa for animal feed. The orchards of course, took a lot of work, but we had beautiful fruit: apricots, peaches, pears, apples, plums and cherries. We trucked a lot of it out of Fruita for cash sale or traded for grain with other farmers near Loa and Lyman. All my children were raised here, and attended the one-room school. Life wasn’t much different from 1880, when pioneers first settled here. You had to be very self-sufficient to make it. Most everybody here had been raised as Latter Day Saints, but some weren’t very active. We held Sunday School over in the schoolhouse. The eight or so families here got along pretty good, considering the isolation. Oh, we didn’t agree on everything; I remember Cass Mulford supported Hoover while I was a Roosevelt man, myself. Both men and women worked hard here, but we took time to play. Our family enjoyed high country hunts and fishing. The women quilted. We read a lot in the winter and enjoyed baseball in the summer. We saw few travelers here until after 1937, when the park came. Most were cattlemen and sheep herders. There were huge herds of sheep trailing through Fruita in those days. For me, Fruita was paradise. I will never forget it."

George Dewey Gifford, 1899 - 1997 (97 years old)

Nearby was an old shed built around 1925 by Merin Smith, a fruit grower and occasional blacksmith who came here after WWI as a hired hand to 'Tine Oyler. He married Oyler's daughter, Cora, and lived here many years. He bought the first sports car, a Ford V8, and later the first tractor in 1940.

This Power Horse was made by Eimco in Salt Lake City and designed so that so that farmers could operate it using reins from the towed, horse-era implements.

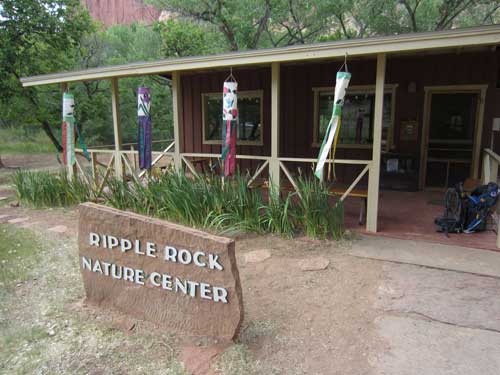

Directly across the road was a Nature Center. Again there was ample info and displays on the geology and history of the area.

Hopefully some of these names are starting to sound familiar.

Learn what it is like to grind corn into meal on a 'metate' using a hand-held 'mano' like the Fremont people did.

Or milk a cow like the Mormon settlers did.

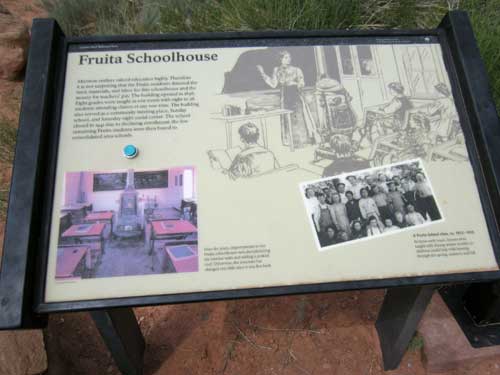

Also nearby was the old schoolhouse. Mormon settlers valued education highly. The local residents donated all the land, materials and even the teacher's pay. The building opened in 1896, with all eight grades being taught in one room, ranging from 8 to 26 students. In the early years, classes were only taught during the winter months so that the children could help with farming for the rest of the year.

The building also served as a community meeting place, Sunday school and Saturday night social center. It eventually closed in 1941 due to declining enrollment and the few remaining students had to be bused elsewhere.

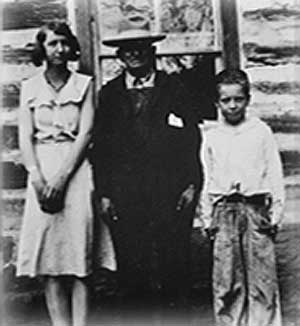

Janice Oldroyd Torgerson shares her story.

My name is Janice Oldroyd Torgerson. And I taught here in 1934 as a brand new teacher. I was a native of Wayne County, but Fruita was a rough 25-mile drive from my parent’s home in Lyman. I received $57 a month for a seven-month contract and boarded at ‘Tine Oyler’s home here in Fruita. There was no electricity or indoor plumbing, but Fruita was beautiful. Across the dusty road, were row upon row of grapes, bordered by huge walnut trees. On moonlit nights, the majestic red cliffs seemed gentle and protective. The school building was sadly in need of repair and mud was falling from between the logs. We had only a few old ragged books. Like many rural children of the day, some of my students were pretty rough-and-tumble. The language I heard was too rugged for me, and I came down hard on that. Then there were the inevitable tricks. One morning I received a dead snake, coiled menacingly on my chair. I gathered some gentle recollections, too. I especially remember the happy faces of young Lloyd and Fay Gifford, when they gave me a handkerchief at Christmas. It was a pretty rough year for a new teacher, and frankly I was relieved as school end drew near. The folks at Fruita gave me a surprise party the last evening before I left. The Mulfords and Giffords came with food; we played games and danced in the Oyler’s crowded living room. By noon the next day, I was on my way home. Just before Fruita disappeared from view, I stopped, sat down on a rock, and thought about the eventful year just past. I found a lot of happy memories while sitting there, and cried a little, knowing it was over.

Janice Oldroyd Torgerson (1912 - 1991) with 'Tine Olyer and a student

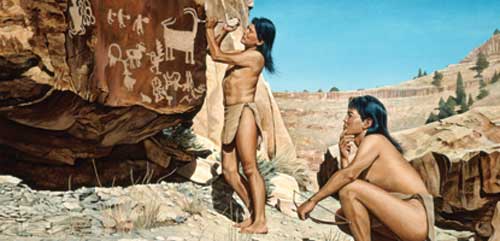

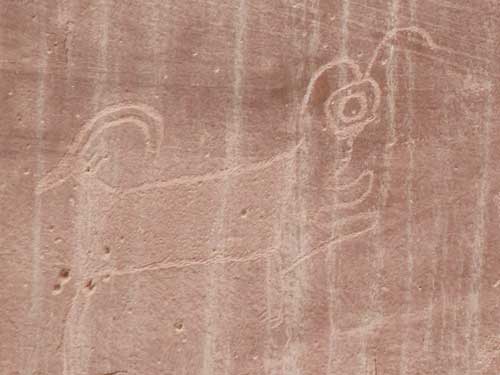

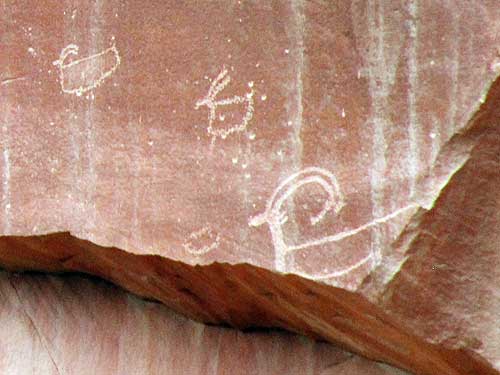

Just down the road was the stop for the petroglyphs. This was the talk I was hoping to catch but missed. The ranger was still there answering questions though. And carved into the giant cliff wall directly in front of us... the petroglyphs.

The earliest records of Paleo-Indians in Utah date back to 12,000 years ago. Archaeologists believe they arrived during the last Ice Age by the Bering Land Bridge and were the first North Americans. Few artifacts remain, however, making their lifestyle difficult to fully understand. However, it is suggested that they lived in rock shelters and caves and hunted megafauna, such as mammoths. When these animals became extinct due to climate change, these Paleo-Indians adapted to an Archaic lifestyle of nomadic hunting and gathering. They moved through these canyons 8,000 to 1,600 years ago, hunting bighorn sheep, deer, elk and pronghorn. They made baskets and clothing; they made stone tools and wove nets to trap game; they ground seeds and nuts into paste of flour.

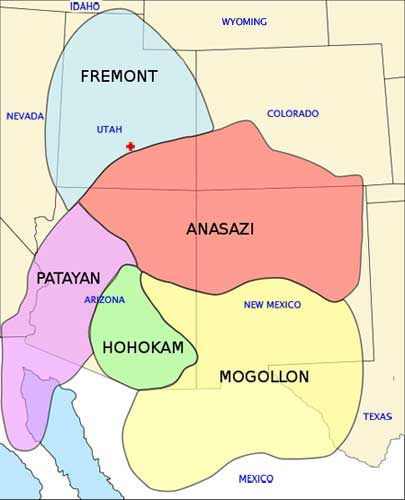

The Fremont culture (named after the Fremont River where the first sites were discovered) existed throughout Utah, Idaho, Colorado and Nevada from around 600 to the 1300's. They are defined by a consistent set of traditions and practices which differ from other contemporary cultures such as the Ancestral Puebloans (or Anasazi). Some of their most distinctive items were their baskets and pottery. Also, unlike other tribes who wore fiber sandals, they made moccasins from animal hides.They also built stone granaries. But perhaps their most unique artifacts were unfired clay figurines of people.

The red plus marks the Capitol Reef area

Distinctive clay figurines

Animal hide moccasins

They lived in pit houses and natural rock shelters, probably in small groups consisting of several families (even during peak years they never built huge cities). These groups gradually changed over time, merging and dispersing, in a process known as residential cycling. This reshuffling continued for thousands of years and resulted into todays' tribal groups of Utes, Paiutes, Hopi, Navajo and Zuni.

It is believed they were hunter-gatherers who supplemented their diet by growing corn, beans and squash near the rivers. Since they often lived in marginal, high-altitude environments, they had to make frequent modifications to their lifestyle as conditions changed. There is no clear single factor as to why their culture ended. During this same time, there was lots of cultural change and population movement throughout the entire Southwest.

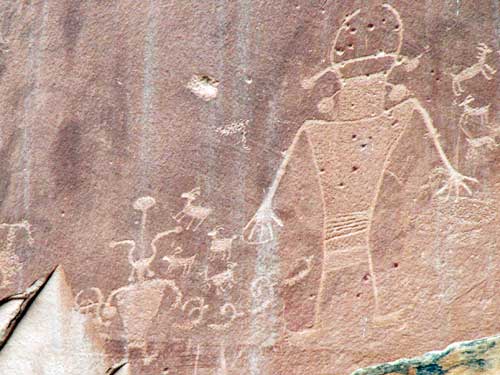

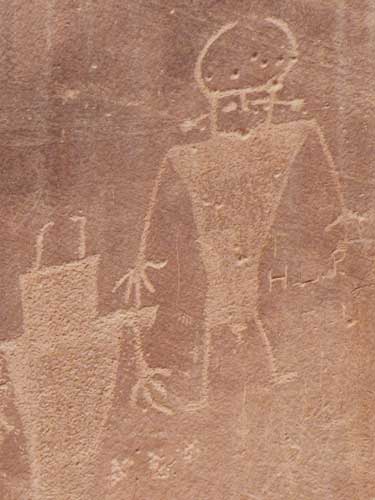

Pictographs (painted on rock surfaces) and petroglyphs (carved into the rock) depict people, animals and abstract designs. The meaning is unknown although numerous guesses have been made.... religious or mythological events, migrations, hunting trips, resource locations, travel routes, celestial information, etc.

Locations of petroglyphs

Clearly many images have been lost due to natural erosion.

Hear the words of Mckay Richard Pikyavit, the last living Chief of the Paiute people.

Maik’wuustuhkoov’un. Hello my friend. My name is Rick Pikyavit. My Southern Paiute ancestors were roaming and hunting the canyons south of here when white settlers arrived in the 1880s. Long before the Mormon Pioneer, or any tribal memory, other Native American peoples came to know the canyons and cliffs of the Waterpocket Fold. We call them the Fremont Culture, because we don’t know what they called themselves. Unlike my own ancestors, the Fremont people did not move with the changing seasons. They took root in these watered canyons and became farmers as well as hunter-gatherers. They left few signs, even though they lived here longer than the five centuries between the voyage of Columbus and the present day. Other people like them lived over the large portion of what is today called Utah. For the most part, the story of the Fremont people can be told only in questions, not answers. How closely these people are related to the better-known pueblo-building Anasazi, no one knows. There are striking differences, as well as similarities. Many archeologists think that Fremont people may be descended directly from ancient nomads called the Desert Archaic. We know a little about the Fremont people’s daily lives from collections of precious artifacts, and something about their hearts and minds from their petroglyphs. We know less, almost nothing, about where they came from or why they left suddenly in the 13th century. For park visitors, some Fremont Culture petroglyphs can be viewed easily. Caution must always rule in the interpretation of petroglyphs. With few exceptions, we cannot really be sure what the ancient maker of the petroglyphs had in mind. Among serious students, there are some who consider almost all petroglyphs a form of writing, while others consider most of them to be art, not writing. The large trapezoid-shaped human figures excite interest. Many have headgear and horns. Figures are commonly seen with necklaces, earrings and sashes. Animals, especially bighorn sheep, appear in many petroglyphs, and indications are that they were once often hunted and perhaps revered. Following the disappearance of the Fremont people in the 13th century, no one resided in the Waterpocket Fold country for 500 years. During this time, however; Ute and Southern Paiute hunters and gatherers roamed the region. They lived in close harmony with the natural environment, and left little evidence of their presence. Here in the Fremont River Valley, archeologists first identified the Fremont Culture. As you walk these paths and hidden places, do not even touch the petroglyphs. Protect their legacy, even as I respect it.

"The Last Paiute Chief" McKay Richard Pikyavit (1930 - 2004)

return • continue