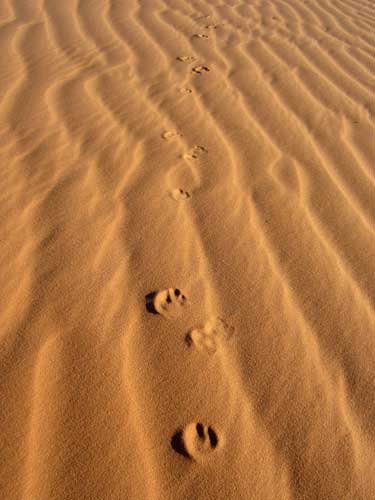

I got up at 6:15. It was finally quiet aside from the crows making all sorts of silly calls. I was packed up and gone before anyone was up. I did a short morning hike at another set of dunes. This time I was able to use my own tracks to find my way back.

What was highly interesting about the sand was if you looked away from the sun, it looked orange...

... but if you looked toward the direction of the sun, it was white.

Evidence of those who passed through here before me

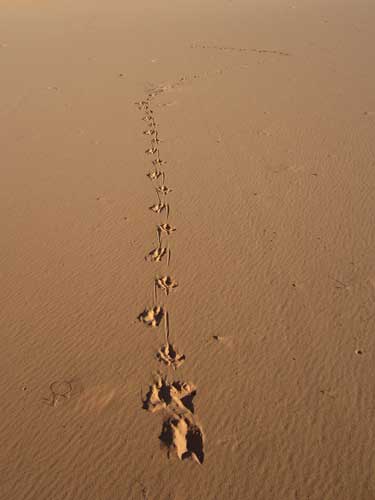

A bird landed, strolled a bit, then flew off.

Bird, lizard and small rodent

Our endangered Welsh's Milkweed again

Evening Primrose blooms at night and begins to wilt in the morning.

There were many different textures of sand. Some areas even had a sort of thick crust.

It was unclear what these bizarre formations were.

These only make sense...

... when seen from above. Obviously something has been clearing out a home.

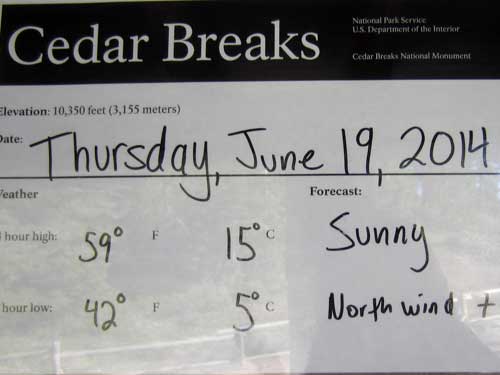

It was a looooong way up to Cedar Breaks which is above 10,000 feet elevation.

Ouch!

All the highway signs had little beehive pictures. The Mormon pioneers called this area 'Deseret' which according to the Book of Mormon was an ancient word for honeybee. The beehive was the emblem for the provisional State of Deseret in 1848 as well as was on the flag when Utah became a state in 1896. The state's motto is"Industry."

Trees began to replace desert shrubbery.

I arrived at the ranger station (located at Point Supreme) at 9:30 am so I had a bit of time to view the magnificent scenery before the geology talk at 10 am.

Cedar Breaks was declared a national monument in 1933. This very same year also saw the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a federal program designed to create jobs during the Great Depression. The nation's national parks and monuments benefitted greatly from this.

Click for a larger version

There aren't many roads in the monument... basically just the 6-mile scenic drive that leads past a few overlooks and trailheads. The road is generally only open to cars from late May to late October (due to the heavy winter snows) but remains open year round for various winter sports.

It's going to be cold tonight!

In 1937, 27 men from the CCC began construction of the visitor center and ranger cabin. The buildings were designed to be as much a part of the natural environment as possible.

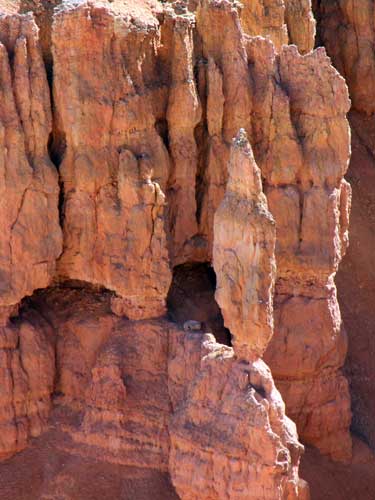

Daphne was our ranger for the talk. She first explained that this giant hole in the ground is technically an amphitheater... not a canyon. A canyon is formed by a river. There is no river at the bottom here. This is formed by erosion. While melting snow and summer monsoons play a part (the plateau drops an average of four feet every 100 years just from all the sediment carried away in the form of beige waterfalls), the biggest cause is the freeze/thaw effect. This area has over 150 nights per year of freezing temperatures. Water freezes in the cracks and pushes off the weaker pieces of rock. In 2007, a large 8-foot piece of cliff fell off right by visitor center (one can still see the metal of the old fence).

The amphitheater is 2,500 feet deep and more than 3 miles across.

Scale

Remains of the old fence

The fins keep getting thinner and thinner. When they get thin enough, they will form windows and even arches.

This arch on the amphitheater floor faaaar below is actually very very tall.

Daphne broke the geologic history down into chapters.

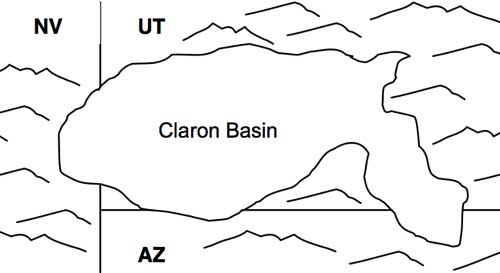

Chapter 1 (60 million years ago): This was a giant flat bowl (250 miles by 70 miles wide) surrounded by mountains. Lots of rain washed sediment down into the basin, creating a shallow, muddy, murky lake called Lake Claron. The snail was at the top of the food chain. Over time, the sediment began to settle out, creating rock layers. Calcium (from the snail shells) formed the binding material and created limestone [sandstone is located much deeper near the bottom of the amphitheater]. Many nice distinct layers were formed. Minerals from the surrounding mountains led to the different colors: reds, oranges and yellows mean iron oxides; pinkish purple is from manganese oxides; white is pure limestone.

Daphne used a water bottle to demonstrate settling sediment.

This was about the size as present-day Lake Erie.

Chapter 2 (30 million years ago): This was a time of active tectonics.... massive volcanic eruptions (there are still 250 cinder cones in the area with eruptions as late as 2,000 years ago) as well as weak places in the crust where magma could come up. Rhyollitic rocks are visible from this time. These giant explosions added material and made faults and fissures in the rock layers... including Hurricane fault (between here and Cedar City) and Siever fault nearby.

Chapter 3 (10 million years ago): The faults became vertically active. The Nevada side dropped while this side elevated. This all happened very slowly over millions of years. Cedar City is now 5,700 feet whereas we are at 10,300. It is interesting to know that it is still moving too! We rise about 2 millimeters per year and the Great Basin is still dropping.

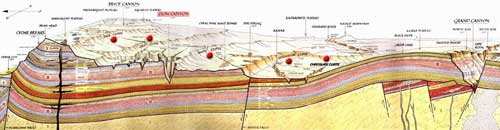

She then discussed the Grand Staircase, that I had first learned about in Zion. These are the five large steps of the plateau named by color. Chocolate is the oldest and the deepest. We are the youngest.

Pink Cliffs (Cedar Breaks)

Grey Cliffs

White Cliffs (Zion)

Vermilion Cliffs

Chocolate Cliffs (Grand Canyon)

Click for a larger view

The trees have very short branches. This is because the area gets 15 - 20 feet of snow per year.

The dead-looking tree is a Bristlecone pine and is very much alive at over 1,000 years old. This is actually an adaptation to this difficult climate. It can shut down water to dead or damaged parts of itself. The oldest bristlecone pine in the monument is over 1,600 years old.... but actually this is considered young. In other areas, the trees can get up to 5,000 years old.

A very hyper White Crowned Sparrow

Chiming Bells (or Aspen Bluebells)

Alpine Prickly Currant