PETRIFIED FOREST (Day 6 - part 2)

Our next stop was Nizhoni Point which means 'beautiful' in Navajo. It is where we could see what is known as an unconformity. An unconformity represents missing rock layers which in turn represents missing time... in this case, 192 million years!

How did this happen?

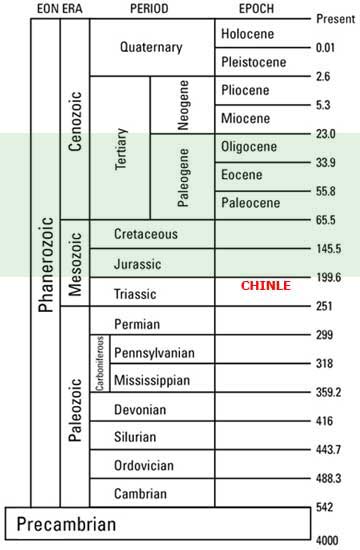

About 225 million years ago, the supercontinent Pangaea began to break up, shifting around the earth's crust. Still as a result of this process, this area (known as the Colorado Plateau) began to rise about 60 million years ago, in some places reaching up to 10,000 feet. Then several million years of erosion to begin stripping away the many layers of rock all the way back down to the Chinle Formation of the late Triassic (235 - 200 million years ago). The erosion stopped and new rock of the Bidahochi Formation was added on during the Miocene and Pliocene of the Tertiary period (4 - 8 mya).

Where the Bidahochi and Chinle Formations meet is called an unconformity. It's like a geology textbook with missing pages. You can tell that pages are missing but you can't tell what was on them. It simply jumps from the Chinle Formation (over 200 million years old) to the Bidahochi Formation (only about 8 million years old). 192 million years of rock are simply missing.

The plateau covers around 130,000 square miles.

The green section represents the missing layers of rock.

The unconformity is between the black Bidahochi basalt on top and the white and red sedimentary Chinle below.

There is actually very little Bidahochi Formation left in the park.

Most of the rock in the park belongs to the Chinle Formation. During the end of the Triassic, large river systems flowed through this region to the sea (where Nevada sits today). They deposited over 900 feet of silt, sand and gravel, burying their channels and floodplains and eventually resulting in the now exposed colorful bands of rock. The different colors are the result of the level of the water table. When the water level was high, there was less oxygen in the sediments which gave the iron minerals in the soil a greenish or blueish hue. When the water levels fluctuated, the iron minerals were allowed to oxidize (or rust), causing more of a reddish color.

Our next stop covered an entirely different kind of history... that of Route 66.

The highway first technically started in 1857 as a wagon road ordered by the U.S. War Department along the 35th parallel. In 1925, the government created the U.S. Highway System, a nationwide network of numbered highways. Before that, auto trails were owned by private organizations. In general, odd-numbered routes would run north-south (with the lower numbers starting in the west and going higher as you moved east) and even-numbered ones east-west (with lower numbers in the south). US 66 was intended to connect the rural communities that had no prior access to a major national thoroughfare. It would stretch from Chicago, Illinois, to Santa Monica, California, covering a total of 2,448 miles. Road signs were erected in 1927 but it wasn't completely paved until 1938.

In 1956, however, the Interstate Highway Act was signed into existence. President Dwight D. Eisenhower felt that more direct routes were a necessary component of a national defense system. Gradually parts of the once-great highway began to be upgraded or bypassed. By the late 1960's, much of it had been replaced by Interstate 40 and it and it was officially removed from the United States Highway System in 1985. In areas such as here, I-40 replaced it directly, upgrading it to Interstate standards. Portions that went through cities became business loops. And so, it is no longer possible to drive Route 66 uninterrupted all the way from Chicago to L.A... although pieces of the original road still survive.

Route 66... the Will Rogers Highway... Main Street of America... the Mother Road

Bill and Joanne stand next to an old 1932 Studebaker.

This stretch of Route 66 (now I-40) was open from 1926 to 1958.

We then moved on to the Puerco Pueblo (located near the Puerco River) which gave us glimpses into yet another kind of history... the ancient peoples of this area.

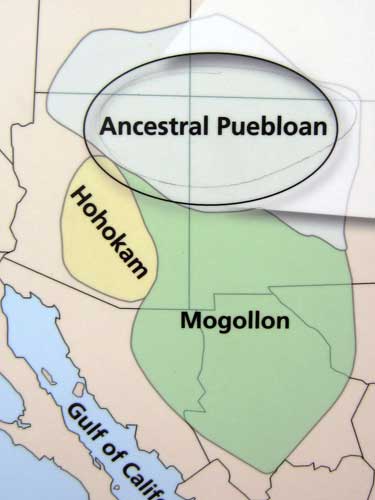

People have lived in this area for over 13,000 years. This village was built around 1250 by the Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi. The latter term, however, was given to them by the Navajo and means "ancient enemies." Out of respect for their descendants, which includes the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma and Laguna, archeologists tend to use the new name.

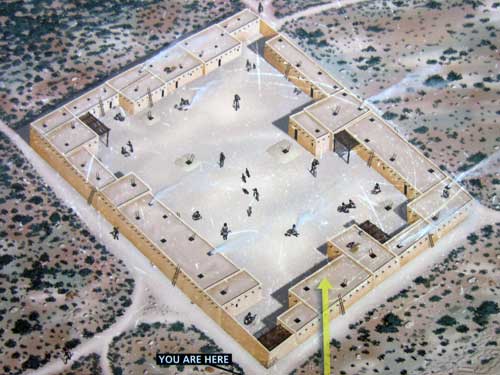

The pueblo was one-story high and built of sandstone blocks, shaped by hand and mortared together with mud. It had over 100 rooms (including living quarters and storage rooms) and was home for up to 200 people. They lived here until around 1380.

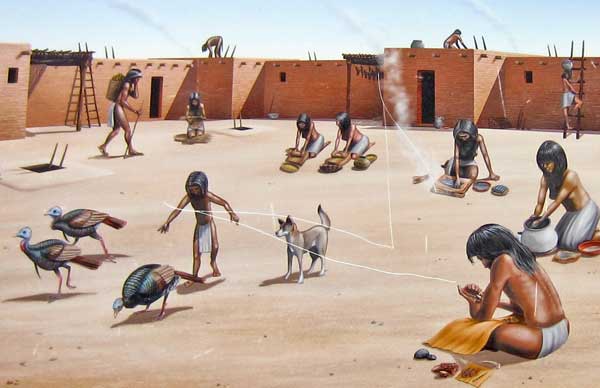

The people grew fields of corn, beans and squash. Daily tasks included the preparation of food, and the making of tools, pottery and baskets.

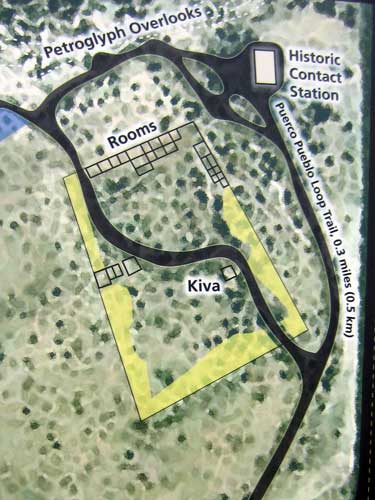

A map of the area. Only about 1/3 of the site has been excavated, and some of it has even been filled back in to preserve the remnants of walls and floor.

The rooms may look quite small, but people didn't live indoors as we do today.

A kiva is a subterranean room for ceremonial and religious functions. It would have been covered over with flat roof with a hole that served as an entrance (you can see one in the above drawing of life in the pueblo; it's on the ground on the far left with a ladder sticking out of it).

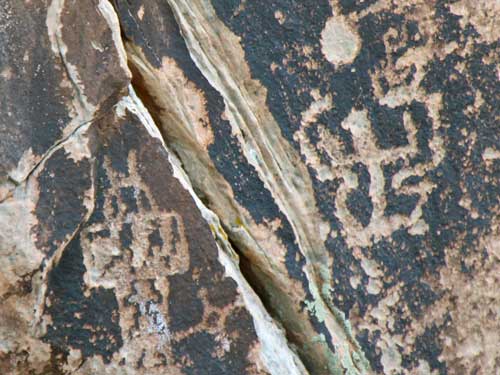

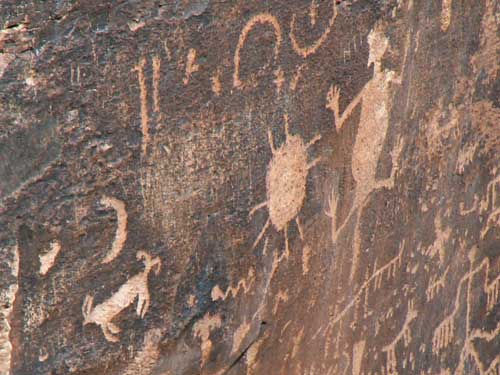

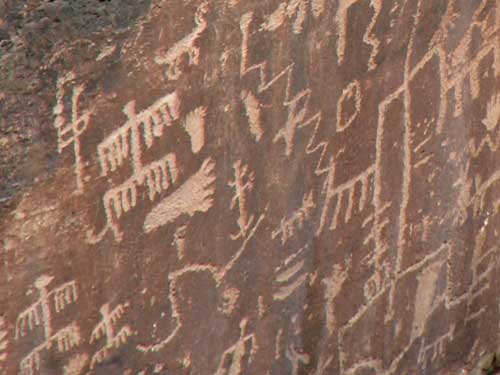

We then wandered over to the petroglyphs. A petroglyph is an image carved into the dark coating on the rocks, exposing the lighter material underneath. The coating is called desert varnish and consists mainly of iron and manganese oxides mixed with clay and organic material that accumulates over time. A pictograph, on the other hand, is an image actually painted onto the rock, not scraped off.

We first walked out to the summer solstice marker.

A solstice is an astronomical event that happens twice a year as the sun reaches its highest or lowest point in the sky. Here, a crack in the rock and a symbol carved on the rock mark the summer solstice.

But why would they care? Prehistoric people used solar calendars to plan for the changing seasons... when to plant crops or expect summer rains, for example. There are over a dozen such calendric petroglyph sites within the park.

How it works

On the solstice, light comes through here...

... and hits this solstice mark.

Farther down were several more boulders covered with images. The images represent ideas that the artists were trying to communicate to the world around them. Unfortunately we no longer know exactly what the symbols mean, but we can make educated guesses by referring to present day traditions.

The Zuni believe this rock art depicts the clan ties of the artist... the Crane Clan and the Frog Clan. But another interpretation tells of a story of a giant bird who came to the villages to eat bad children. Or it could simply be of the native White-faced Ibis that lives here. Ultimately it's your call what you want it to be.

A migration symbol

Kachinas, or spirit beings, started to appear in the region around 1300. Similar symbols are found on modern Puebloan pottery and weavings.

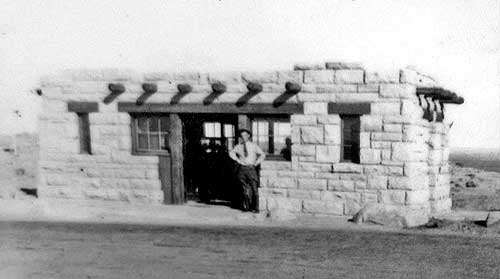

In the far corner was the historic contact station. This region was added to the park when it was expanded in 1930. This building was constructed to serve as entrance station in 1935 and modified in the 1940's to be a visitor center with museum exhibits. In the 1960's it was a rest area and in the 80's it had been fully converted into a restroom. In 2005, it was closed and boarded up, and finally in 2014, it underwent restoration to what it is today.

The station in the 1940's...

... and today

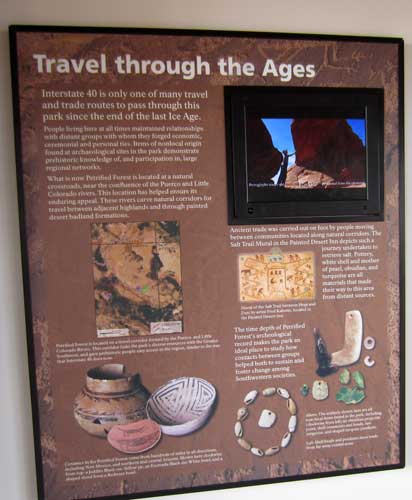

Inside was covered with information and exhibits.

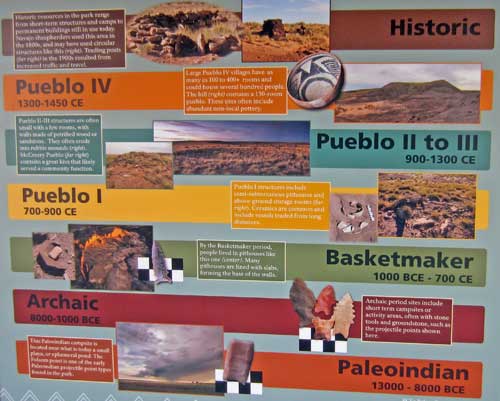

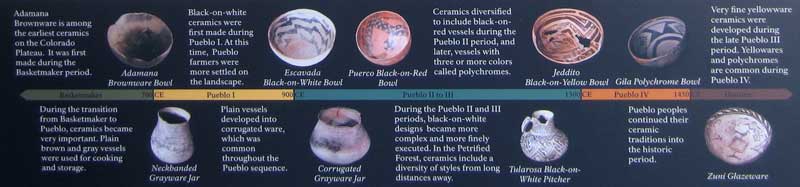

The different periods are based on significant cultural changes, such as housing or skill development.

Paleoindian (13000 BC - 8000 BC) - hunters from the last Ice Age, campsites, stone points

Archaic (8000 BC - 1000 BC) - short term campsites, stone tools and points

Basketmaker (1000 BC - 700) - pithouses, woven baskets, early farming

Pueblo I (700 - 900) - semi-subterranean pithouses, ceramics

Pueblo II & III (900 - 1300) - small pueblo villages (such as Puerco Pueblo)

Pueblo IV (1300 - 1450) - large villages, non-local pottery

Historic (1450 - present) - Navajo settlements, trading posts, ranchers, etc

For the prehistoric inhabitants of this area, the petrified wood made for excellent tools such as knives, scrapers, drills and arrow heads. Since shapes and styles change over time, archeologists can sometimes use them to determine the age of a site.

The Puerco River served as a travel corridor across the Colorado Plateau and there were many communities settled along it. The Puerco Pueblo would have been visited by travelers and traders from all over the southwest. As a result, many non-local artifacts have been found in the park such as costal shells, turquoise, obsidian...

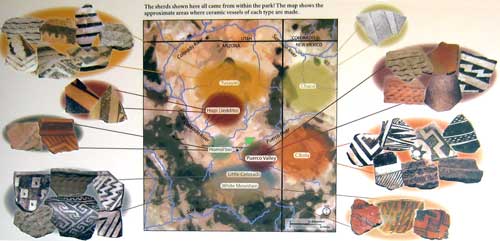

...as well as ceramics from all locations, cultures and times. (Click for a larger view)

Styles of pottery change over time.

We returned to the car and were promptly approached by a large raven. It gave up quickly once it realized it wasn't going to get any food from us.

Crows and ravens can be hard to tell apart. The best clue is usually the voice, but species differ in other subtle ways too. The Chihuahuan Raven is intermediate between crows and ravens in many ways. It has the shape of a raven but is the size of a crow.

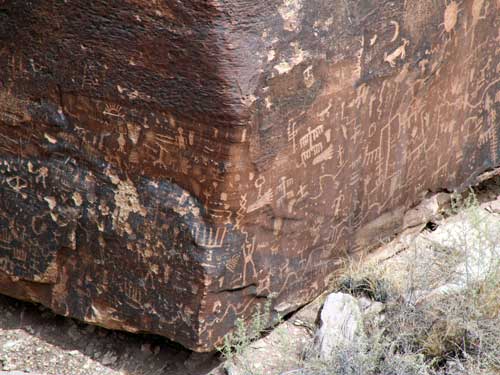

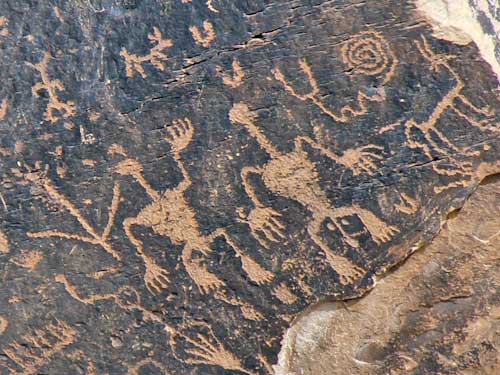

We drove on to Newspaper Rock, which is one of the park's largest concentrations of petroglyphs. More than 650 images are scratched into the rocks below. They were created between 650 and 2,000 years ago.

More ravens stalk the parking lot.

Again, their meanings aren't known but they include human and animal images, spirals and geometric designs and also hand- and footprints.

return • continue