CUMBRES & TOLTEC TRAIN (Day 2 - part 2)

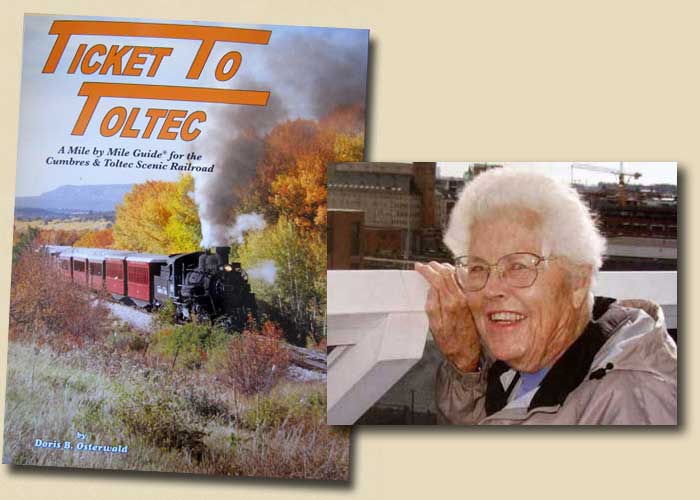

Four long, loud blasts of the whisle signaled our departure. Our trip was enlightened by a lovely guide book (written by the wonderful Doris B. Osterwald), filled with incredible information, photos and maps covering every mile of the journey.

Another good source of information on our trip was Tom, our docent. A docent (coming from the Latin word docere, which means 'to teach') is a trained volunteer who becomes an expert in his subject or tour. Tom does this trip about three times per week and was a wealth of interesting facts and stories.

Passing the station's water tank

Our conductor takes our tickets.

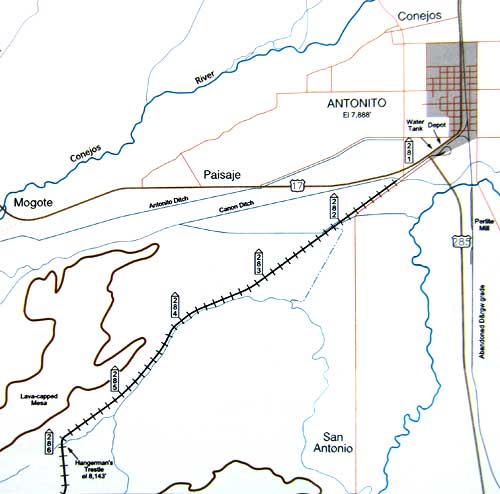

This is one of the few sections where the track is actually straight! Our cruising speed was around 15 miles per hour.

San Antonio Peak (elevation 10,935) is a sealed, dormant volcano.

Some of the oldest irrigation projects in Colorado are in his area. Ditches bring water down from the mountains to the valleys. The first ditch was dug by hand in 1852. Today's farmers have it a bit easier.

Crossing the shaky, jiggly, loud connection between cars

I ended up spending a lot of time in the open viewing car instead of in my seat...

... but the price was a lot more soot and ash! The twin mountains in the far distance are the summits of Los Mogotes Peak (elevation 9,818), another small volcano. It was originally named Prospect Mountain.

The next section of our journey was a lot more twisty.

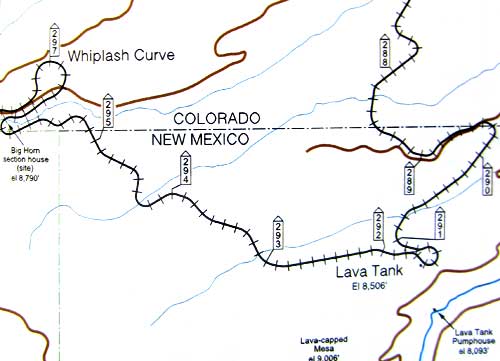

The first of many crossings back and forth with Colorado. The boundary between the two states was first surveyed in 1868. Errors forced a second survey in 1902-3. But this would have drastically reduced the size of Colorado. Loud protests from property owners along the border continued until 1925 when the first survey was considered legal. It has since been resurveyed and the boundary has been readjusted in some areas.

Sagebrush, rabbitbrush and native grasses are the dominant vegetation in this semiarid region.

Our ascent begins!

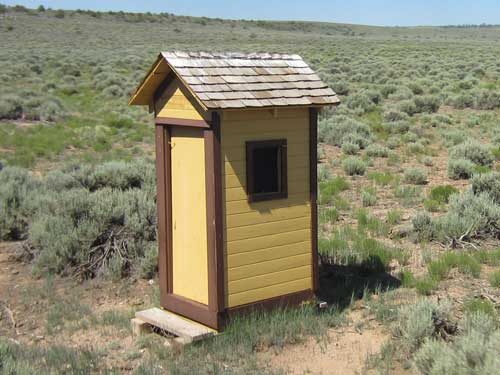

This is one of the old phone booths that once served as a means of communication. We were told to also keep a lookout for some of the old poles, complete with old steel wires.

Our brakeman enjoys the convenience of modern communcation.

Now THAT'S a remote job!

Passing by Lava Tank, elevation 8,506 feet

The original tank burned down in 1971. This current tank (currently not in operation) was brought over from Antonito. Water is actually pumped up from the Rio de los Pinos River via a pumping station, built in 1883. It took 2,230 feet of pipe to run water up to the tank.

Lava Tank gets its name from this stuff... Cisneros Basalt deposited 4.7 - 5.3 million years ago.

'Road' crossing

Turkey vultures circled overhead.

A large herd of pronghorn darted across the track and up into the thick brush.

Back and forth, back and forth state lines

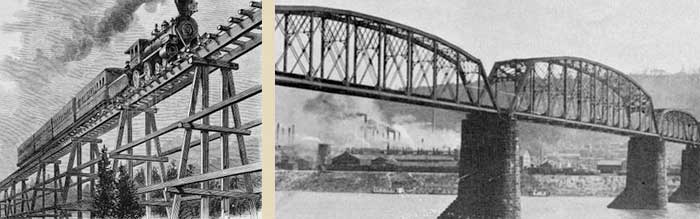

Crossing over trestle 296A. The original bridge, built in 1886, was much longer.

A trestle (left) is a type of bridge made up of short spans supported by splayed 'trestles' (individual rigid A-frames). Other bridge types (right) use longer spans which rest on support structures in the middle and at either end. The word comes from the 12th century French word 'trestre,' meaning crossbeam.

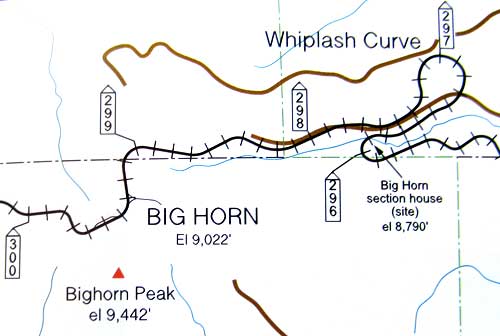

Coming up out of Whiplash Curve. The lower tracks we were just on can be seen midway up the hill.

We also got a glimpse of the tiny 'fire truck' that was following us the whole way.

Steam engines run on coal; burning coal can produce embers; embers can land on dry brush and cause fires. These guys were making sure we weren't causing any trouble.

Leaving Whiplash Curve

Another volcano with visible lava layers

Looking down on Whiplash Curve...

... and trestle 296A

One of the many old phone poles, including steel wires

The vegetation has slowly been changing. Ponderosa Pines now start to make their way into the picture. Since leaving Antonito, we have gained almost 1,400 feet in elevation.

An old petroglyph or a bored hiker?

The boiler is under a lot of pressure. Every now and then, the engineer will need to blow it out, to clear out any sediment. But he can also use these water jets to clean off the engine.

No. 463 gets a bath.

We reached the Big Horn Wye and Siding, completed in 1880. Helper engines could turn around here and the siding could hold 28 cars. This was a frequent meeting point for trains.

A herd of cows rests beneath the trees.

Again the scenery changes as aspens appear.

While many trees spread through sexual reproduction (flowering), aspens usually reproduce asexually via a process called suckering. An individual stem (tree) can send out lateral roots that send up other erect stems. From above ground, the new stems look just like individual trees. But they aren't; they're just clones. The process can be repeated until an entire grove forms.

The engine works hard. Between Antonito and Cumbres Pass, the train can use 2 - 3 tons of coal.

return • continue