GUNNISON (Day 19 - part 1)

We just happened to wake up early so we left early and hence were among the first to arrive at the park (or at least the visitor center).

In 1929, Reverend Mark Warner promoted preserving this amazing canyon. A few years later, the answer to his numerous letters was granted and the area was proclaimed a national monument in 1933 and a national park in 1999.

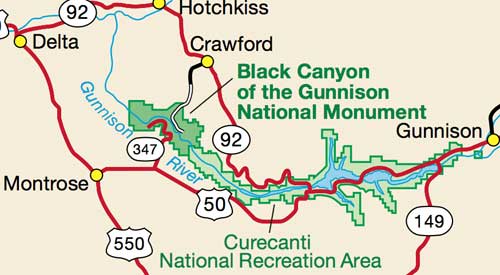

It contains 14 miles of the canyon's total 48-mile length.

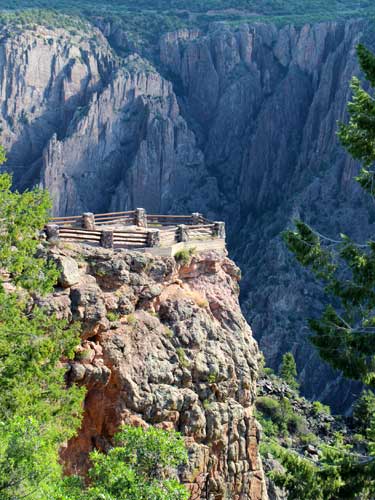

Our plan was to do the 7-mile South Rim Drive from Tomichi Point to High Point. (Click for a larger view)

Our first stop was the overlook at Tomichi Point. The sun wasn't very high in the sky yet, allowing the canyon to retain some of its dark mystery.

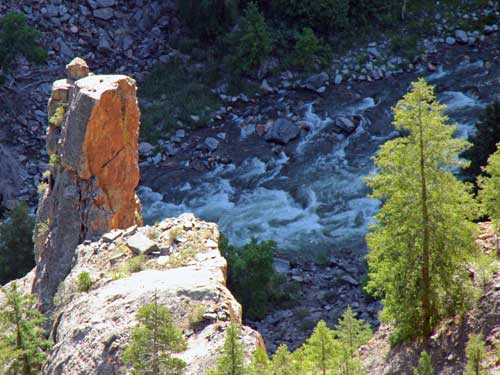

A glimpse of the Gunnison River far below

The visitor center offered many great exhibits, an informative movie and a stunning overlook of the canyon.

While not as 'grand' as some of the other canyons we've seen on this trip, this certainly was the narrowest and steepest. It is so narrow and steep, in fact, that parts of the gorge only receive about 30 minutes of sunlight per day... hence giving it its name.

A relief map offered a clear perspective.

9 is our location now; 10 was Tomichi Point.

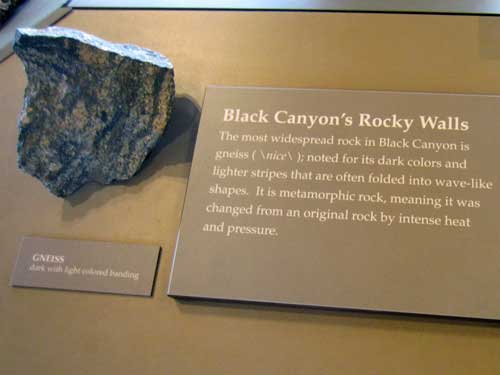

Gneiss (pronounced 'nice')

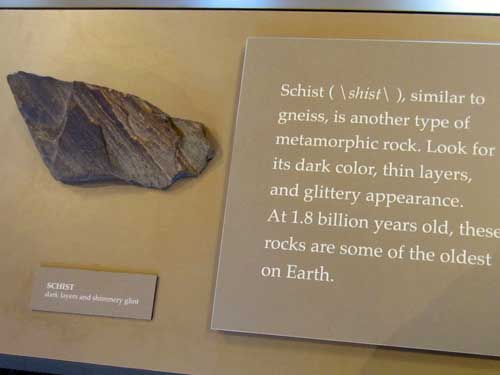

Schist

An exhibit on life in and around the canyon

Joanne learns about the Black-capped chickadee.

An up-close-and personal view of our Yellow-bellied marmot, the same one we saw in Fruita.

The Black Canyon has been a long-time barrier to people. Only the rims, never the gorge, have shown signs of human occupation. Surveys of the canyon began in 1873, at which point it was deemed 'inaccessible.'

In 1853, Captain John Gunnison led an expedition through Colorado to locate a route for the transcontinental railroad... although it's doubtful he even looked into the canyon that bears his name.

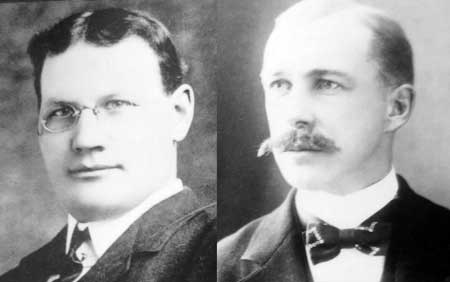

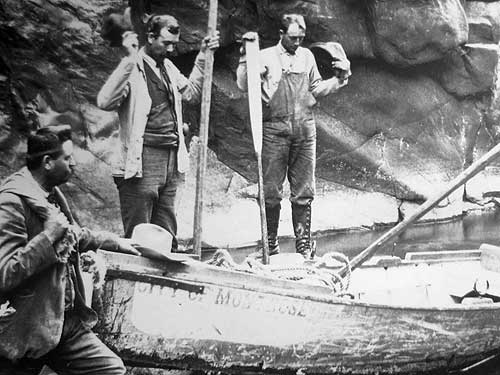

William Wellington Torrence (1873 - 1921) and Abraham Lincoln Fellows (1864 - 1942)

In 1900, five men, including a William Torrence, attempted a trip with two wooden boats to scout out a good location to dig an irrigation tunnel to divert the river for farming in the neighboring arid valley. Their first shattered boat on first day and they lost most of their supplies. After 3 weeks, the local townspeople were convinced they had drowned and stretched a net across the river at the mouth of the canyon to catch the bodies. Fortunately the men eventually returned, cold, wet and hungry, having abandoned the mission and scrambled their way to the rim.

Torrence tried again 1901, this time with Abraham Lincoln Fellows. The men floated down the river on inflatable rubber air mattress for 33 miles and 9 days. Instead of carrying many supplies, they arranged spots to have provisions brought down from the rim. Once having found a suitable location, the 5.8-mile Gunnison Diversion Tunnel was dug from 1905-09. Labor was so intense and dangerous that most men only spent 2 weeks on the job. Today it still diverts river water for the irrigation of the surrounding farmland.

I think the best part of this pictures is that the two men on the left are wearing jackets, vests and even ties!

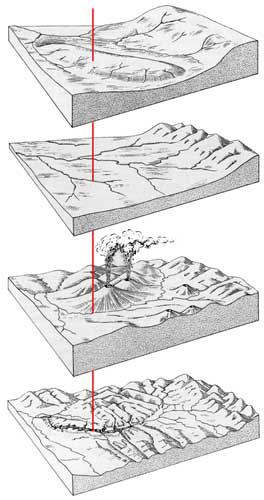

"You are here" as the canyon is formed over the millennia (click for a larger view)

About 65 million years ago, a large section of hard Precambrian rock was thrust upward, forming a bulge on the earth's surface. Known as the Gunnison uplift, this was to be the location of our canyon. But why would a river chose to carve through such a hard path when there was softer rock all around it?

Over the next 30 million years, the nearby Sawatch Range became greatly eroded. These soft sediments filled in the area, creating a broad flat plain over which streams easily meandered.

Then repeated volcanic eruptions occurred, forming the West Elk Mountains to the north and the San Juan Mountains to the south. The Gunnison River had no choice but to flow over the narrow path between them... directly over the uplift.

Once it began its downward cutting, however, it became entrenched and could no longer alter its course once all the softer rocks were gone and it reached the hard rocks of the uplift.

The movie offered us a more animated creation of the canyon.

Bill and I then set out to the overlook.

Our destination

The visitor center...

... where Joanne decided to oversee our antics from afar.

An oak with young acorns

Mountain mahogany

The rocks glittered and sparkled with...

... Muscovite Mica, which was once used in making heat resistant windows. It is named after the city Moscow, the main source of the material in earlier times.

A long way down

The river has been carving through this hard core for 2 million years. With an extremely steep drop (averaging 96 feet per mile within the canyon. For comparison, the Colorado River drops an average of 7.5 feet per mile through the Grand Canyon), the water has the power to cut through the hard rock relatively quickly (about one inch per century - remember, it is super hard rock). It carves more slowly nowadays because dams upstream prevent seasonal flooding. Originally during spring runoff, the river could carry rocks weighing up to 700 pounds.

We then started on the overlooks. When we had arrived at the visitor center, no one was there. Now as we headed out, it was packed with busses and tourists. We fortunately were always able to remain one stop ahead of the big crowds. Our first stop was the Pulpit Rock Overlook.

Our destination

The flowers of Sulphurflower buckwheat start out bright yellow but become orange or even red with age.

Almost at the end

The south rim (right) has eroded back farther than the north rim. The south rim doesn't receive as much sun as the north rim so it doesn't dry out as quickly. A moist slope erodes faster than a dry one. What the river can't carry away accumulates as steep piles of talus or scree. Scree comes from the Old Norse meaning landslide, and talus is French for slope or embankment.

return • continue