OURAY (Day 18 - part 2)

On our way to the mine...

Prominent avalanche chutes

Cunningham Creek, which flows into the Animas River nearby

Looking down Cunningham Gulch

Snow still lingers in July up here.

A beaver lodge and small dam

The history of the Old Hundred Gold Mine begins in 1872 when Reinhard Neigold arrived from Germany. Joined by his brothers, they together formed the Midland Mining Company in 1882 and had several claims here, on the extremely steep side of Galena Mountain (named after galena, the primary ore of lead, with a high silver content). The big lower vein was called the Number 5 vein while the upper one was the Number 7. One of the claims in 1898 was named the "Old Hundred." The Neigolds spent many years successfully mining the mountain. But to tap the supposedly super rich veins deeper in, a long tunnel would have to be dug, and this was money the brothers didn't have. So in 1904, they sold the mine.

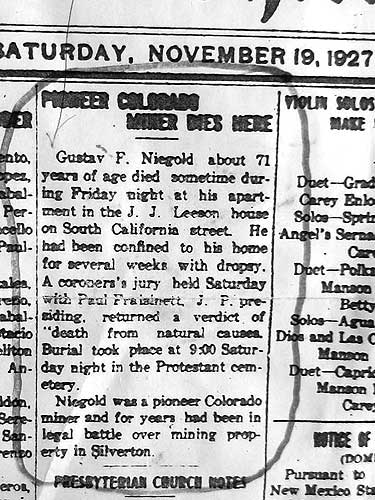

The new owners, the Old Hundred Mining Company, invested hundreds of thousands of dollars for more tunnels, connecting shafts, roads, trails, three aerial tramways, boarding houses, cabins and a large stamp mill (where the ores were crushed and the valuable metals separated). But they never recovered their investment. By 1908, all the good gold was mined out; the veins consisted of quartz and little else. In the end, they defaulted and the Neigolds got the property back. The brothers tried to sell it but no one wanted a money-losing investment. Eventually, it was lost to back taxes, and in 1927 the last of the Neigold brothers passed away.

Several more attempts were made to revitalize the mine over the decades. It was bought and sold and bought and sold... all after substantial financial losses. Even a Texas oil company tried its hand with no luck. Finally, in the 1970's, most of the buildings were torn down and the equipment was sold. Nothing was left except for the long since abandoned boardinghouse high on the mountainside and miles of empty tunnels.

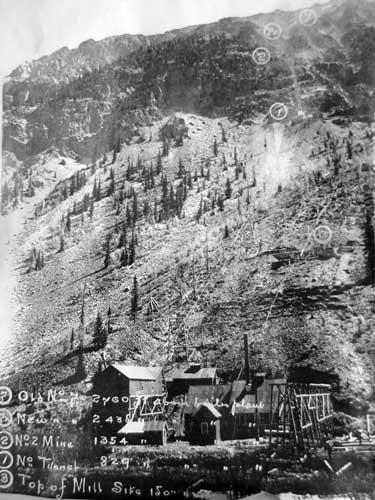

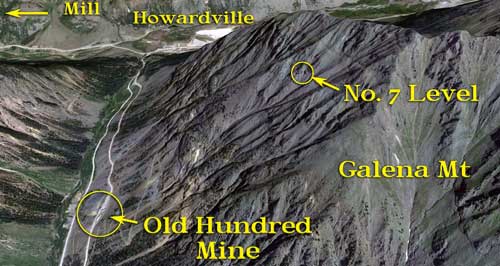

The levels of the mine (click for a larger view)

The Number 7 vein lies at 12,000 feet elevation, over 2,000 feet above the creek below.

1904 photo of the 40-man boarding house (left) and tram house

A top view

The final Niegold brother passes away.

An old bridge

A small cascade bounces its way down the extremely steep hill.

These large copper buckets were used for taking water out of mines.

You could pan for your own gold and silver...

... or just buy it in the store.

Bill and I suited up for our tour. An electric-powered mine train would take us 1/3 mile into the mountain where the temperature was a cool 48 degrees F. Joanne decided to sit this one out.

We're about to disappear into this mountain!

Loaded up...

... and on our way!

A 3-minute long, very fast, very loud ride bounced us through the darkness. Water dripped from the ceiling and the air cooled quickly.

We spent the next 45 minutes exploring some of the lower level passages. This level was worked from 1968 to 1971.They never got a single ton of ore out of it but it certainly provided us with a nice tour!

This tunnel is called a 'drift' because isn't straight but rather follows the vein.... the No. 5 vein in this case. Veins run 800 feet above us and thousands of feet below. They can get up to 20 feet wide.

30 million years ago, there was a volcanic upheaval and eventually the mountains formed. But two to three million years later, the whole area sunk (called the Silverton Caldera). Water flowed in and mixed with minerals. Hot water in the form of geysers flowed out. This caused the cracks to refill with minerals (hydrothermal replacement) which became the veins we see today.

Following our guide down the passageway. Due to the upper levels, there is natural ventilation so air does not have to be pumped in. There is sometimes even a slight breeze as a result of the constant temperature: air flows out when it is warmer outside and in when it's colder out.

Quartz, gold, silver, copper. Some 6 - 7 tons of ore silver was extracted from above veins. While it is still in the walls here, it's not worth the cost to try to extract it.

Especially not with this! The walls are comprised of very, very hard granite and quartz. A pick axe and shovel are no match for it.

In order to mine this mountain, drills and explosives were required. A single hammer and chisel could only advance 6 inches per day. Even two men (with one swinging the hammer and the other holding the chisel) could only do 18 inches per day.

In 1876, power drills that ran on air were invented. Two men could operate it like a jackhammer. Eventually they were designed so just one man was needed to run it. Now they could do 4 feet in just 10 minutes. Unfortunately this created lots of dust, but not just dust... dust mixed with silica (which is basically glass shards). Once inhaled, it cut up the lungs, causing scar tissue and eventually death by silicosis. Men who operated these drills only had a 41 year life expectancy.

In 1898, George Miner. created drill that was even worse. It was nicknamed the Widowmaker. It was so bad that miners started refusing to work. So the drills were recalled and redesigned from air to water. This resulted in a much safer wet slurry instead of the lethal dust.

This Ingersoll 'Leyner' column drill from the 1930's weighs 300 pounds. It would take about 30 minutes to set up and was extremely loud... 100 decibels. With extended exposure, noises over 85 can cause permanent damage and eventual hearing loss. We all covered our ears as our guide turned it on for a demonstration!

In 1947, the Jacklight came along. It is still in use today. Weighing only 130 pounds, one person can drill 6 feet in 5 minutes.

Stoping drills extended from the bottom and could drill down 7 feet deep. A stope is a step-like excavation made to extract ore.

A steady flow of water ran throughout the passage.

The darkness within. This drift goes another 200 feet back. Keep in mind that for many years all this work was done simply using candlelight.

A skip is an elevator in a mine. This one held 6 men with tools and explosives.

The 'raise' went up 650 feet. A 'shaft' is dug from the top down whereas a raise is dug from the bottom up. They are easier to build.

A coffin skip was meant for just one person. It was used in narrower stopes. The turquoise color in the background is copper.

The motor that pulls up the skip

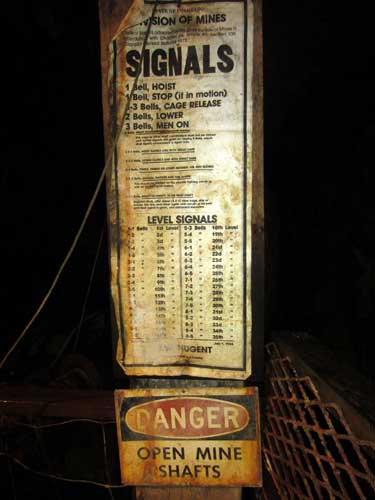

A miner had to ring a bell to signal the skip operator. This was very important job. The operator had to watch for a mark on the rope otherwise the cage could fall. He literally didn't want to 'miss the mark.' (Click for a larger version)

Raises often had ladders as well, in case the skips stop working.

return • continue