MESA VERDE (Day 16 - part 3)

It wasn't too much longer before we arrived at Mesa Verde National Park.

Bill and Joanne decided to join in on the fun with their own pass.

Table Mesa (meaning green table) got its name from Fathers Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante (remember them?) as they traveled through this area in 1776. They didn't get close enough to see any cliff dwellings though. And technically they misnamed it.... it's not a mesa but rather a cuesta. Cuestas are similar to mesas, but instead of being relatively flat, they dip in one direction.

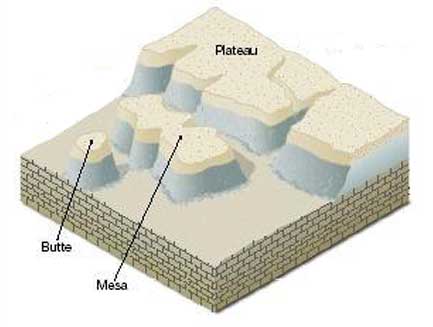

A mesa - an isolated, medium-sized, flat-topped highland with steeply sloping sides or cliffs, topped by a cap of much harder rocks that are resistant to erosion. A mesa started life as a flat plain. Eventually rivers and streams eroded away the surrounding area.

A cuesta - a mesa that gently dips in one direction.

A butte - a mesa that has mostly eroded away, leaving a narrow pointed top or a very small flat top. The size definition is in some ways quite arbitrary. Basically, the early settlers said if you could find game on top or graze cattle, that it was a mesa. Anything smaller was a butte.

A plateau - looks like a huge mesa, although it doesn't necessarily have to be isolated (often just one side has a cliff). They could also be formed though a giant uplift due to tectonic forces.

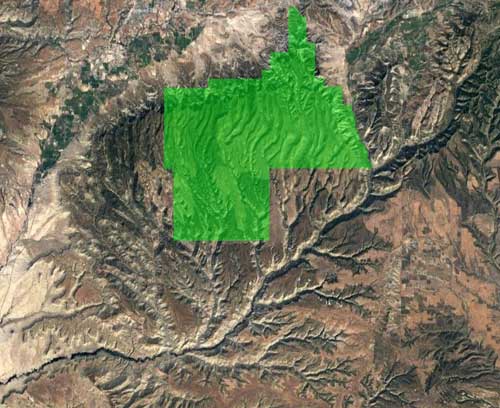

"Cuesta Verde" is inclined to the south at about a 7 degree angle.

Table Mesa has been deeply dissected by wind and water erosion into a series of north-south canyons and 'mesa tops.' It was once was connected to the San Juan Mountains but has long since been isolated. The national park covers only a section of the mesa.

Mesa Verde National Park, established in 1906, is the only national park created to preserve the culture and architecture of the Ancestral Puebloans. Over 4,000 archaeological sites and 600 cliff dwellings are protected. Local ranchers first reported the cliff dwellings in the 1880's.

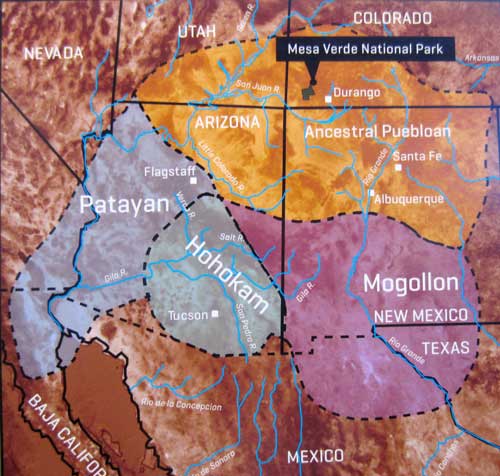

Click for a larger view

Our first stop was the visitor center.

The Ancient Ones, sculpted in 2012 by Edward Fraughton

How would you like to have to do your grocery shopping like that??

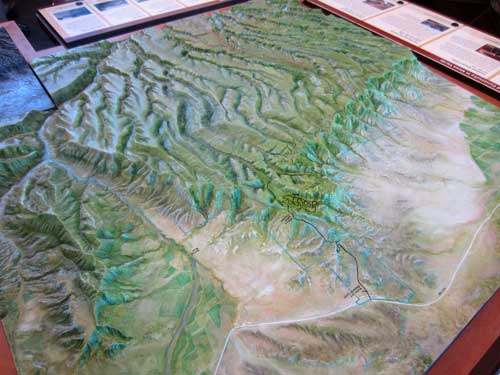

From this relief map of the mesa, the numerous, deep canyons are quite visible. Also note that a river (the Mancos) runs along the side but that no rivers run through the mesa.

The Ancestral Puebloans moved into this area about 1,500 years ago. We used to call them the Anasazi, but since this has a somewhat negative connotation (being the Navajo word for 'ancient enemy'), a friendlier term was chosen. They lived in communities throughout the region, hunting and gathering as well as farming. It wasn't until the last few decades before they left that they began to build the incredible cliff dwellings in the natural alcoves in the canyon walls.

Back then, the Puebloans covered a very large area and had many villages, most of them much bigger than Mesa Verde. As a result, it wasn't very special. We value it now because it serves as such a good window into the past.

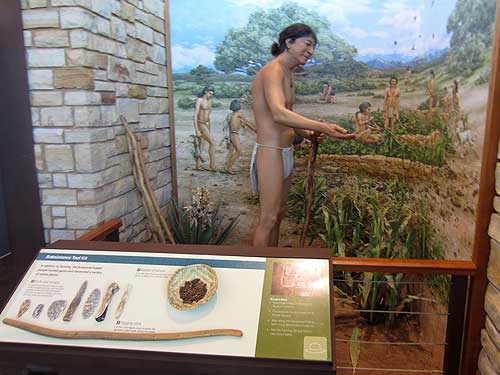

The people grew crops of corn, squash and beans on the mesa tops where the growing season was longer. Maize (or corn) became an important staple crop. Corn farming originated in central Mexico from a native, hybrid grass. It was reliable, highly productive, could be dried and easily stored for many years, and retains its viability as seed for 70 years.

If there were no rivers, where did they get water? Rainfall and melting snow (they could get up to 80 inches during winter!) soaked down through the porous sandstone until it reached an impermeable layer of shale, which then forced the water sideways through the rock. It eventually seeped out of the cliffs in the form of seep springs. For crop irrigation, they built small dams, water diversion systems and catchment basins.

Gathering water from a seep along the back of an alcove. Before they learned how to make pottery, they wove baskets out of plants such as yucca. They then coated them with pinyon pine sap or clay to make them watertight. By dropping fire-heated rocks into one of these baskets, they were able to boil water and cook food.

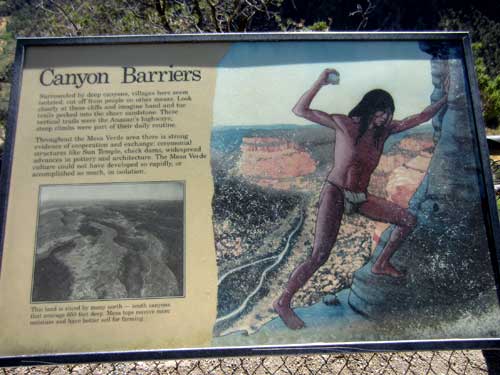

Navigating the steep cliffs using hand-and-toe holes

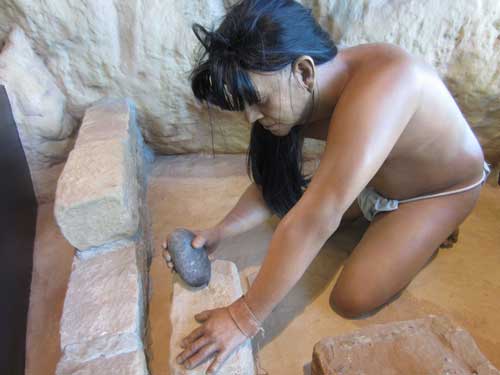

The sandstone bricks were shaped using tools made from harder river bed stones.

Grinding stones for corn

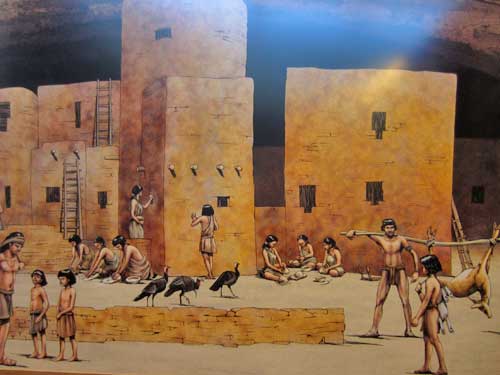

Life at the peak of their cliff-dwelling civilization. Then, for unknown reasons, they all left. By the year 1300, Mesa Verde was vacant.

We headed up to the top of the mesa.

It may be legal in the state, but not federally.

The Point Lookout mesa

Curving our way up

The top of the mesa

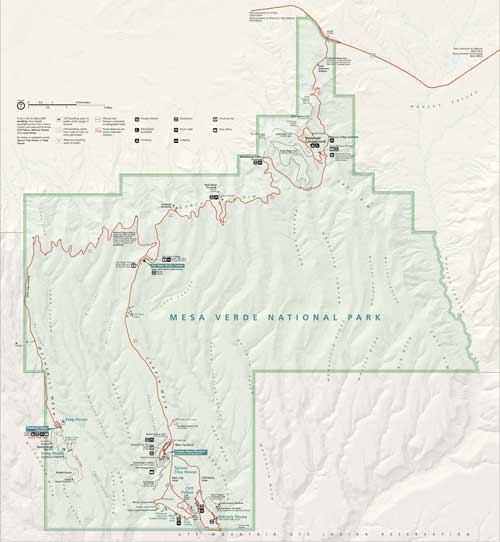

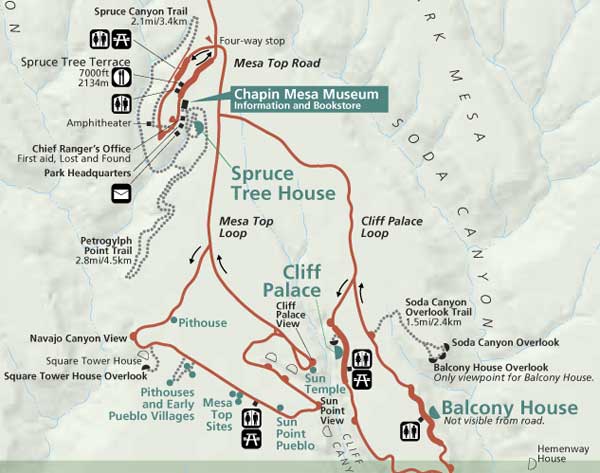

The park is essentially divided along two mesas: the Wetherill Mesa and the Chapin Mesa. We weren't going to take any of the tours so we opted to just see the easy sites along one of the loops at the end of Chapin Mesa.

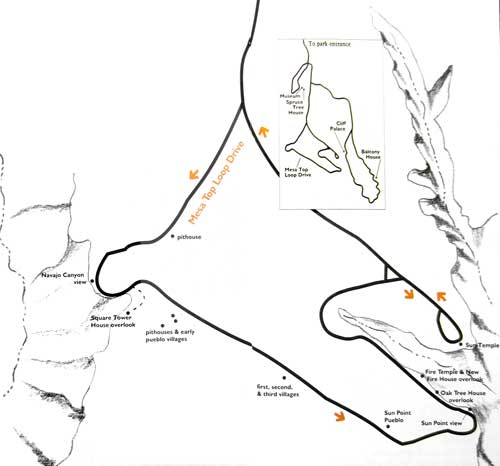

Our plan: the Mesa Top Loop

Click for a larger view

Most of the large fires are caused by lightning.

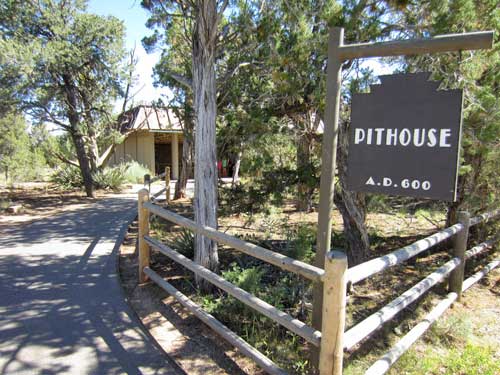

Our first stop was a pithouse from the year 600. This was still early on in their cultural development. Pithouses were the first permanent homes after hundreds of years of a nomadic lifestyle of following game and other food sources. By staying in one spot and growing crops, population began to grow rapidly in size and cultural complexity.

Basically they went from being semi-nomadic to pithouses to single-story villages (around 750) to multi-story villages to cliff dwellings (in 1200) to leaving the area (in 1300).

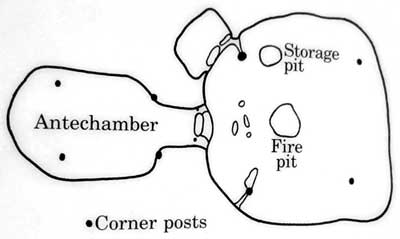

Built partially below ground, this was a common layout for all pithouses in the area at this time. Bits of burned adobe and charcoal on the floor indicate that this dwelling burned down.

The antechamber may have been used as a storage room.

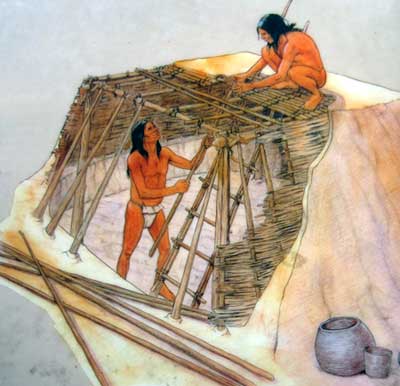

Shallow pits were dug into the ground then structured with poles and mud, with an entrance through the roof via a ladder.

Next stop was the Navajo Canyon Overlook. This is one of numerous canyons (that average 650 feet deep) that slice the mesa north to south.

While these canyons may look impassible to us, the cliff dwellers actually had a whole network of trails connecting them to the mesa tops and to one another. These steep climbs consisted of many hand-and-toe holes pecked into the sandstone cliffs.

Next was the Square Tower House Overlook.

It was a short walk to the overlook.

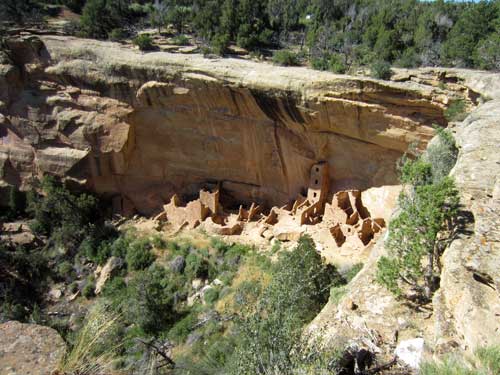

This alcove dwelling was occupied from 1200 - 1300. It contained 8 kivas and at some 80 rooms (60 of which remain today). They got up here using hand-and-toe holds, ropes and ladders.

The four-story tower was the tallest man-made structure in the US until the mid-1800's... at 86 feet.

The tower in 1907

Cliff dwellings are often situated on unstable foundations, built of native stone and earth, and are vulnerable to weathering, erosion and rock fall. The Ancestral Puebloans had to work constantly to maintain them. The National Park continues that work today. But despite all that, an estimated 90% is the original buildings.

This dwelling was first recorded by a local rancher, Richard Wetherill, in 1888. In 1919, rubble and debris were removed and repairs were made. In 2013, the tower was again preserved.

Note the T-shaped door in the upper left corner. These are common throughout Ancestral Puebloan architecture. It is uncertain whether they had a practical function or were just symbolic. The wider top might have provided more space for carrying material inside whereas the narrow part would have helped conserve heat. Or perhaps it was a way of identifying a room from a distance since they seem more prevalent at public and shared living rooms and not for storage. We might never know.

return • continue