We woke up early... which was good on the one hand (nobody else was up yet so the streets were empty, making it easy to get out of town) but bad on the other (the 'nobody else' also included the valet parking attendants, making it difficult to get our car). But eventually we were on the road and quickly out of town. It wasn't even 8 am but already quite hot out!

Waiting for service... and we didn't even get a smile.

Leaving Las Vegas

Early morning heat

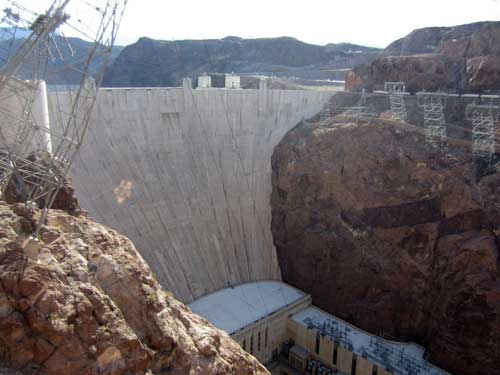

It was a relatively short drive to Hoover Dam. We unwittingly arrived 45 minutes before the visitor center opened... which was good on the one hand (there was already a line and the tour was first-come-first-served, with everything usually being sold out by noon) but bad on the other (it was getting hotter by the minute and there was no place cool to sit).

Lake Mead

Hoover Dam

Much to our joy, handicapped parking was free!

Bill and Joanne decided the tour would be too much walking for them so they returned to the air-conditioned car until the gift shop opened. I was able to get on the first group for the longer tour. Apparently the longer tour had been unavailable for a while... until just now. Lucky me!

Once the doors opened, I went through security, bought a ticket and watched a movie about the dam. We were then assigned tour guides. Alan would give a large group of us the 30-minute power plant tour, then about 20 of us would continue on to another 30-minute tour of the dam with John.

Hoover Dam (originally called Boulder Dam) is located in the Black Canyon along the Colorado River on the border between Nevada and Arizona. Constructed from 1931 to 1936, it was the largest concrete structure that had ever been built.

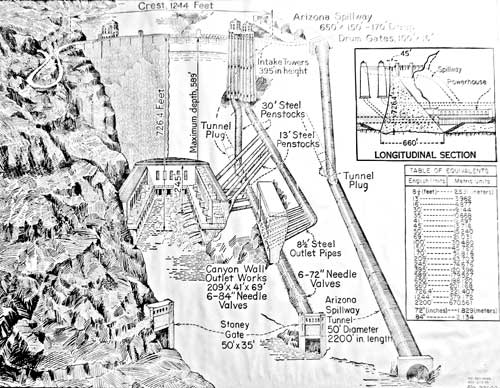

Click for a larger view

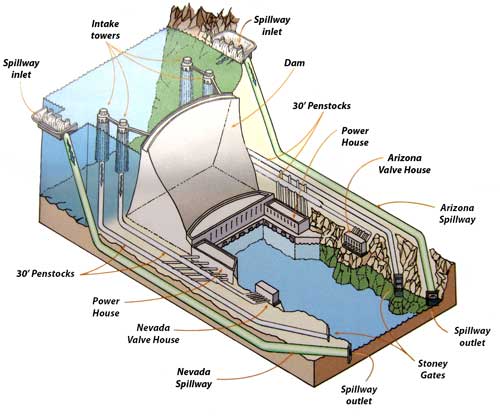

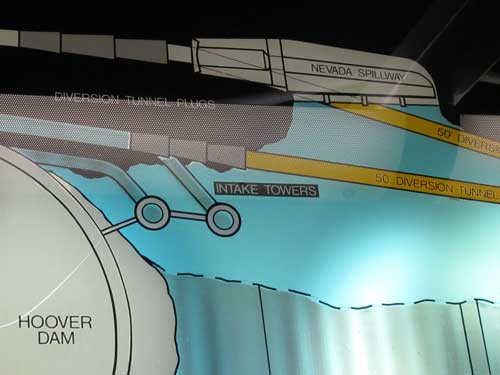

Our first stop was at one of the four enormous diversion tunnels. Before the dam could be built, the Colorado River needed to be diverted away from the construction site. Two tunnels were cut through the canyon walls on the Nevada side and two more on the Arizona side. They were 56 feet in diameter, 4,000 feet long and took two years to build (all the rest of the dam only took another three years). A manufacturing building was actually built here at the dam since pipes of such a huge size were simply too big to ship by train. After that, two built temporary coffer dams were built and then the water was diverted. Construction on the actual dam could now begin.

We took an elevator 500 feet down, then walked to the diversion tunnel

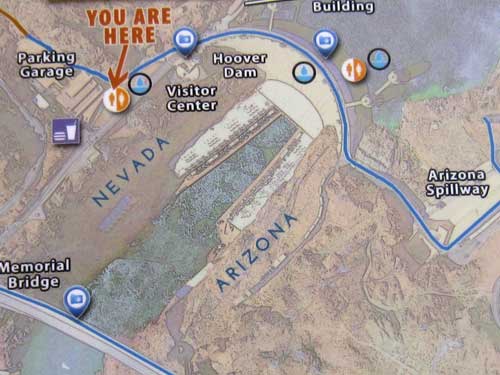

A layout of the dam

The orange sections of the diversion tunnels were closed off once they were no longer needed and were then filled with concrete. (Click for a view of the full diagram)

Overlooking one of the diversion pipes. The pipes now serve as either part of the spillway (which drain water from Lake Mead during extremely high levels to prevent it from flowing over the top of the dam) or the penstock pipes (which carry water to the generator). They are protected under three feet of concrete.

The slight vibration of the building that we felt was due to water rushing under us from the intake towers to the power plant... all 96,000 gallons of it per second.

Another angle (Click for a larger view)

Evidence of water leaks over time

We then headed to the power plant.

Wet walls

Taking an elevator up one floor

The original tour in 1937 cost just 25 cents; today it's $30. Over the years, the dam has seen some 50 million visitors.

There are actually two power plants... with 8 generators in this one (the Nevada side) and with 9 on the Arizona side. Only half of them were running today.

The dam is a peak power plant, meaning it generally only runs when there is a high demand (or peak demand) for electricity. Most of it goes to Los Angeles. As a matter of fact, three of the generators are entirely dedicated to supply the city. How many would you guess are dedicated to Las Vegas? Three, maybe even four? After all, it's right next door and requires a LOT of power to keep all those lights on. As it turns out, Vegas gets ZERO electricity from here. Back then, Vegas was just a tiny town and didn't bid on the electricity. But that contract is over in 2017 so it's pretty much guaranteed they will bid this time!

Each generator is seven stories tall, although most of it is located below the floor. A 65-foot long, 114-ton shaft runs through its center and attaches at the bottom to a turbine (basically a horizontal water wheel). This is where change kinetic water energy (flowing at a speed of 48 miles per hour) is changed into electric energy.

Only those with lights on were running.

Above the generators are mobile bridge cranes (situated on a track). Each one can lift 300 tons (to get an idea, the Statue of Liberty weighs 225 tons). But each generator weighs more than that so the two cranes have to work in tandem.

A Pelton wheel (a highly efficient water wheel generator invented by Lester Allan Pelton in the 1870's) is used for in-house electricity.

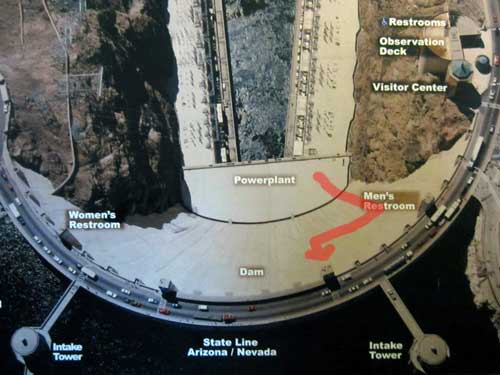

Here is where the tour split up. A majority of the folks returned to the surface while the rest of us continued into the heart of the dam. We were going to take an elevator up 27 levels from the power plant, then follow the main tunnel between the men's room tower and the nearest elevator tower where we would finally ascend another 25 levels to the surface.

The game plan

Continuing on

The change in floor tiles indicate we are leaving the power plant and entering the dam.

All the tiles are original from the 1930's.

Taking the Nevada Dam elevator up

We first went down a side tunnel to the front of the dam. It serves as both an air vent and an inspection tunnel.

This grate that we had to walk over covers a hole that goes 50 feet directly down... although John only disclosed this info after we had all crossed over it!

The view

A bit better view

Heading back

The wear of time

The main tunnel showed lots of evidence of seismic activity. Fortunately the dam was built to flex and move. It was made with 25 foot long blocks that could shift individually. Had the dam been built as one solid piece, it would have failed. Currently it can handle a 8.6 quake before being damaged.

In the 1930's, this was the biggest dam ever built so some new ways of doing things were required. If they had simply filled it with solid cement then 1) it would have failed because of earthquakes (as we already learned) but also 2) it would have taken 100 years to cool. So a network of small cooling pipes were run through all of the blocks. This meant a block could cool in as little as 72 hours.

That said (well, written), the dam is still cooling (and therefore only getting stronger). It will take another 300 to 1,000 years for all the heat to dissipate completely. As it continues to cool, it shrinks slightly...